Elvis History Blog

From King Creole to G.I. Blues:

Keeping Elvis Alive in Hollywood

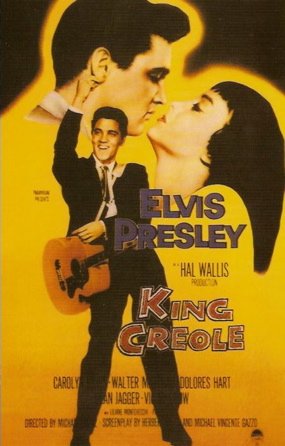

When Elvis Presley attended the King Creole cast party on March 12, 1958, in Hollywood, in the back of his mind must have been some doubt that he would ever attend another such Hollywood celebration. In less than two weeks he would be in the army and his career would be on hold for two years. There was no guarantee that Hollywood would welcome him back. Even though he had signed contracts with three Hollywood studios in the past two years, only the one with Hal Wallis at Paramount was a multi-picture deal. Elvis knew that even that contract was vulnerable. It allowed for five more pictures, but Wallis had options on all of them. The producer could drop them all if Elvis’ star faded while he was away in the army.

Colonel Parker had known for some time of Elvis’ impending military service, of course, and so had begun designing a strategy to keep his famous client prominent in the entertainment industry long before Presley entered the army on March 24, 1958. According to Parker biographer Alanna Nash, the Colonel explained to Elvis the pledge both of them must agree to follow for the next two years. “If you go into the army, stay a good boy, and do nothing to embarrass your country, I’ll see to it that you’ll come back a bigger star than when you left.”

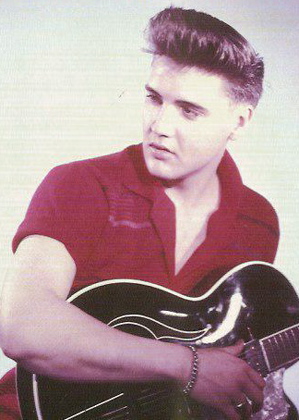

The Colonel’s plan for keeping Presley relevant in Hollywood involved complex negotiations with Wallis and other studio executives, but before he could implement the plan, Parker had to wait for King Creole to complete its run in theaters. The Paramount film premiered at Loew’s State Theater in New York City on July 2, 1958. The film received a mild reception from critics, but Elvis’ dramatic work surprised many of them. In his Chicago Daily News film review, Sam Lesser expressed disappointment in the melodrama but praised Presley. “Elvis,” Lesser wrote, “has a good deal more acting talent than the producers of his films care to utilize … The fast-buck producers apparently haven’t any interest in developing the real Presley who is so astonishingly representative of his time.”

• King Creole disappointed at the box office

In its first week, King Creole ranked number five in box office receipts on Variety’s national rankings. It soon became apparent, though, that teenagers were not flocking to the film in the numbers they had to Presley’s previous three films. An August 13 Variety article noted that the Chicago Theatre pulled King Creole after an initial week of “immediately disappointing business.” To replace it, the Balaban and Katz theater syndicate rushed Naked and the Dead into its Chicago flagship cinema several weeks ahead of schedule.

By the time its run had ended, King Creole had recorded $2.64 million in ticket sales. It made Paramount a modest profit but was a disappointment compared to Love Me Tender ($9.24 million), Loving You ($8.14 million), and Jailhouse Rock ($8.58 million). Both Hal Wallis and Colonel Parker learned the same lesson from Presley’s final pre-army film. Elvis’ fans didn’t care about his acting. They preferred seeing him in musical comedy roles.

With King Creole in the rear window, Parker began implementing his plan to put Presley’s Hollywood career on solid, profitable ground for his return to civilian life in 1960. The basic strategy was to play 20th Century-Fox, Paramount, and MGM against one another. In July 1958, the Colonel lobbed the first shell by floating a claim that a German producer had offered $250,000, plus 50 percent of the profits, for the rights to make a Presley film.

By late October, Parker had successfully renegotiated Elvis’ contract with Wallis. That agreement, signed in April 1956, gave the producer five more pictures, with Elvis receiving $25,000 for the first film with steps up to $100,000 for the last one. The new contract gave Elvis $175,000 for his film in 1960, and allowed Wallis options for three more pictures at $125,000, $150,000, and $175,000 against 7 ½ percent of “gross receipts” after the films recouped expenses.

On October 29, 1958, the very next day after concluding the agreement with Wallis, the Colonel entered into another deal, this time with 20th Century-Fox, for one Presley picture at $200,000 and an option for another at $250,000, plus an even split of profits after expenses. It was understood that these were to be “serious” pictures, in keeping with Elvis’ continuing aspirations to become a “good actor.” (Flaming Star and Wild in the Country were made under the Fox agreement.) Parker knew from King Creole’s poor showing at the box office that it was unlikely films with Elvis in serious roles would play well with his base audience, but it is to the Colonel’s credit that he gave his client an opportunity to make his acting dreams come true by negotiating the two dramatic films at 20th Century-Fox.

• Parker’s bartering with other studios bothered Wallis

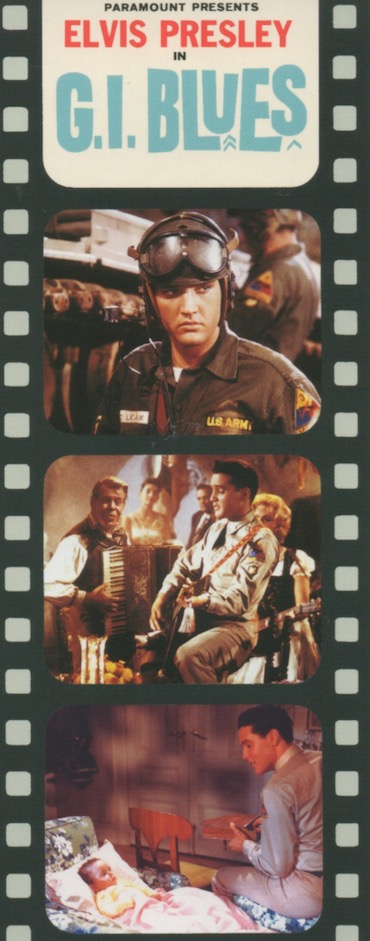

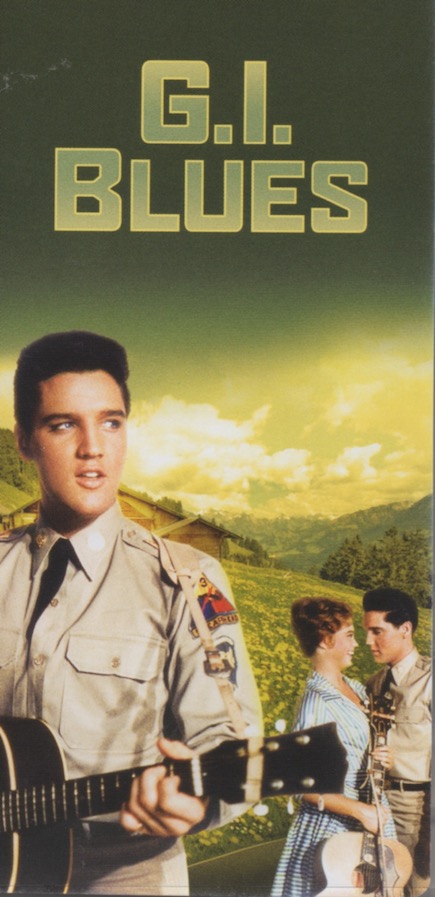

Wallis biographer Bernard Dick explains that the producer, who had plans to capitalize on Presley’s army experience, was disturbed to hear that Parker was negotiating with another studio. “The Colonel had to be reminded that legally Wallis had the right to produce Elvis’ first film after his discharge,” Dick noted. Wallis pacified Parker by raising Elvis’ pay for G.I. Blues to $200,000, plus $50,000 for expenses.

In a letter dated November 18, 1958, to Elvis and his father in Germany, the Colonel touted what he had accomplished with Wallis and at Fox.

“Have just received the report that 20th Century Fox also is picking up the new deal I worked on the past 8 months, so this brings the outlook for Elvis in a pretty solid picture for his future, better than it was before he went into the service. I am sure you both will be pleased with this information. This also will prove to Elvis that he is not backsliding in any way. This now brings our picture setup in line with a very healthy setup for the future … The facts are now we do not have to call on Wallis every time with our hat in our hands to ask for a little extra each time. The improvements I have been able to make will run into at least a couple of hundred thousands dollars more for the first Wallis and Fox pictures when Elvis comes out plus a percentage, which we did not have on either before he went into the service.”

The Colonel’s letter assured Elvis that his manager was fulfilling his pledge to make him an even bigger star while in the service. The letter, along with other regular communication Parker had with Elvis during the army years, also had another purpose. Like most soldiers serving overseas, Presley felt some homesickness, which he at times revealed in letters back home. Still, Elvis had enough self-confidence to tolerate the break in his career. His manager’s updates were important, though, in that they helped him see a clear road in his future.

In a telephone interview with Dick Clark in August 1959, Elvis announced, “I have three pictures to make; one for Mr. Wallis, and then the other two for Twentieth Century-Fox.” In another phone interview with Clark on January 8, 1960, Elvis’ twenty-fifth birthday, Elvis gave his manager due credit. “I’m told that Colonel Parker will have everything arranged,” he said. “I know the first picture is for Mr. Wallis. It’s called G.I. Blues.”

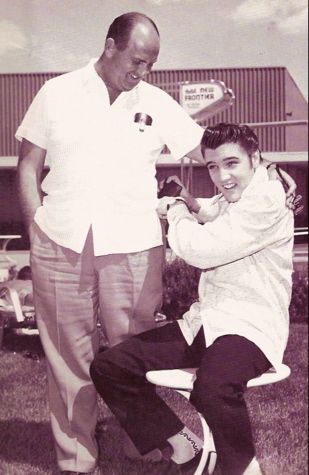

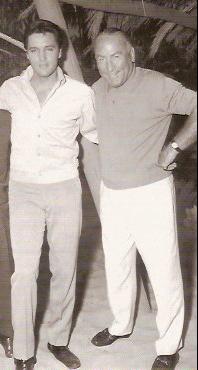

• Wallis came to Germany to meet Elvis

Four months earlier, in August 1959, Hal Wallis had come to Germany to meet with Elvis and shoot some locale footage for use in G.I. Blues. During the three weeks he was in Germany, Wallis oversaw background filming in Frankfurt, Wiesbaden, and Idstein on the Rhine River. Presley’s outfit, the Third Armored Division, supplied tanks and other heavy equipment to the film-makers.

In an interview with Hazel Guild in Frankfurt, Wallis noted that Presley would not appear in any of the footage shot in Germany. “We prefer not to put him in front of the cameras in his working on a commercial film, even in his own time,” the producer said. “The choice was ours. I think if we had asked the army for him, we could have had him.” Previously, Colonel Parker had told Elvis that his was not to participate in any of the filming Wallis would do in Germany.

Wallis mentioned that he realized there might be some publicity value in using German actress Vera Tschechova, who had been dating Elvis recently, in G.I. Blues. After viewing some of her previous film work, though, he decided that she was not right for the role with Elvis. Instead, he said the German female part might go to Erika Remberg.

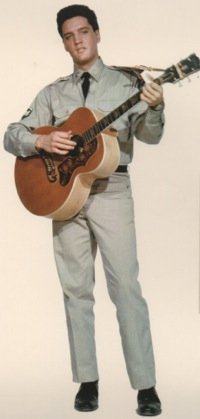

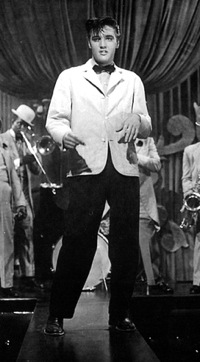

Elvis’ army career had boosted his Hollywood value because of his lack of public exposure while in uniform. Wallis believed that the strict discipline of army life would have tamed Presley’s “personal contortions and gyrations.” He added, “His rhythm will have a cadence as a result of his military service.” The producer revealed that the Presley picture would be shot in Vistavision with a “new super-speed Eastman color process.” Elvis would be on set for about eight weeks, and eight or nine songs would be used in the film.

Wallis’ visit heightened Elvis’ enthusiasm to get back to work. Columnist May Mann reported that Presley asked the producer for a script, but Wallis declined “because he knew his star would have just gone ahead and memorized it on the spot.” Elvis was content, though, just to know his Hollywood career would be revived soon. Even on March 1, 1960, just four days before his release from the army, in an Armed Forces Radio and TV interview with Johnny Paris, Elvis revealed he knew very little about his upcoming movie.

Paris: “You mentioned the movie G.I. Blues that you’ll be doing soon. When do you do the film?”

Elvis: “Well, I can’t give you an official date. It’s after the Sinatra show, which is sometime around the first of May.”

Paris: “And who’ll be in it?”

Elvis: “I don’t think they’ve picked a co-star yet. Not to my knowledge, they haven’t.”

Paris: “Do you know what part you’ll play?”

Elvis: “No I don’t. I haven’t seen the script yet.”

Paris: “So you then, perhaps, have not had an opportunity to contribute any of your own ideas.”

Elvis: “No, not yet. You do that at the filming of the picture.”

While Wallis was in Germany planning his new Presley movie in the summer of 1959, Paramount decided it was a good time to rerelease the two Elvis films it had on the shelf. The studio misjudged the timing, though. Loving You in rerelease only grossed $74,000, while King Creole did little better at $86,000. A Variety article on April 13, 1960, just a few weeks before Elvis’ army release, reported that the other two studios with existing Presley films had chosen a more lucrative time to rerelease them.

“Both Metro and 20-th Fox are picking up some extra revenue with the reissue of Elvis Presley pictures. Metro’s “Jailhouse Rock,” which is said to have grossed $4,000,000 when originally released in 1957, is chalking up steady business in various sections of the country. In some situations, the picture has been played at least three times, particularly in theatres near Army camps. 20th’s “Love Me Tender,” which like “Jailhouse,” was dusted off the week Presley was released from the Army, is also reported to be doing nicely.”

• Colonel Parker’s Promise Fulfilled

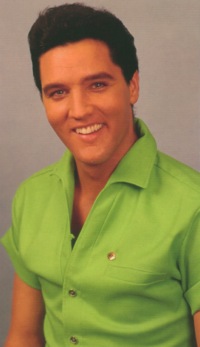

Elvis Presley was released from the Army on March 5, 1960. It only took seven weeks to confirm that Colonel Parker had fulfilled his promise to make Elvis Presley even more popular when he left the army than when he went it. Elvis’ first recording sessions in Nashville produced three blockbuster #1 hits on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 1960. Variety reported that the rating for Presley’s appearance on Frank Sinatra’s TV special in May was “one of the very highest for a prime time one-shot in recent years.”

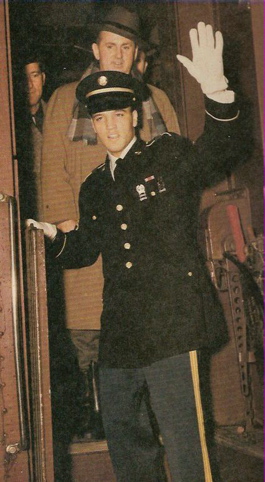

On April 18, 1960, two private rail cars on the Southern Pacific Sunset Limited left Memphis carrying Elvis and his entourage westward toward Hollywood. Three days later Elvis reported to the Paramount lot for preproduction work on G.I. Blues. Two years and a month had passed since he had left Hollywood in uncertainty at the end of filming for King Creole. He returned triumphantly. G.I. Blues would become the sixth highest grossing U.S. film of 1960.

The unique partnership of Elvis Presley and Colonel Parker never worked as smoothly and effectively as it did during the star’s two years in uniform. Presley’s faithful service to his country quieted his critics, and Colonel Parker’s faithful service to his only client had resulted in a smooth transition back to Hollywood. As the years passed, Presley’s film career would encounter obstacles, but nothing can dim the brilliance with which the Presley-Parker partnership managed the years between King Creole and G.I. Blues. — Alan Hanson | © 2017

"Elvis had enough self-confidence to tolerate the break in his career. His manager’s updates were important, though, in that they helped him see a clear road in his future."