Elvis History Blog

Elvis Presley & Buddy Holly …

Contrasts and Comparisons

“Buddy Holly could have been a country singer, or pop crooner, could have and probably would have fitted his talent to whatever music was happening when he came along. It happened to be rock ’n ’roll. But it only fully became rock ’n’ roll the day Buddy Holly started singing it.” —Paul Williams in his book, “Rock ’n’ Roll: The 100 Best Singles”

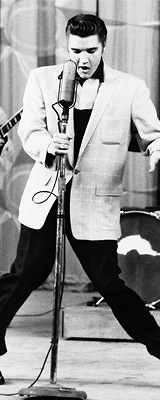

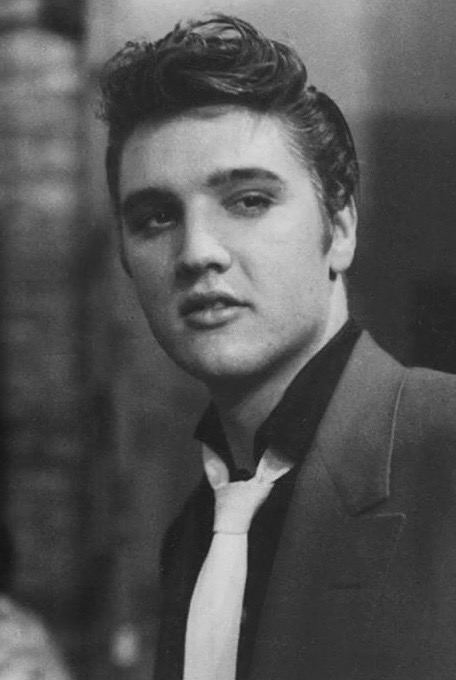

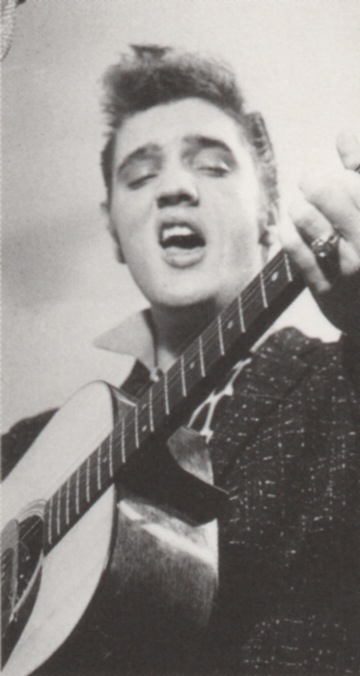

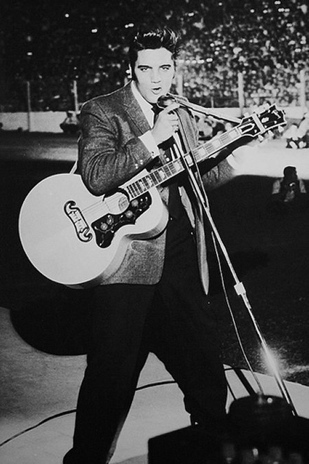

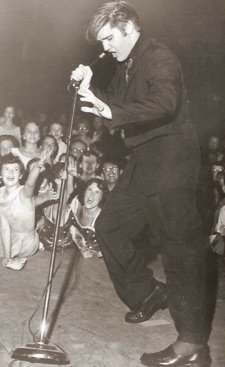

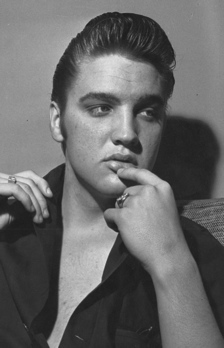

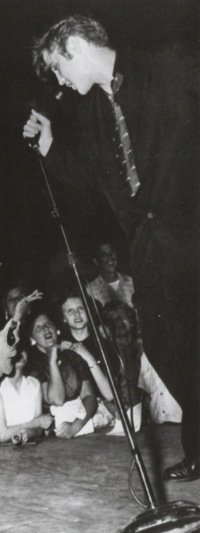

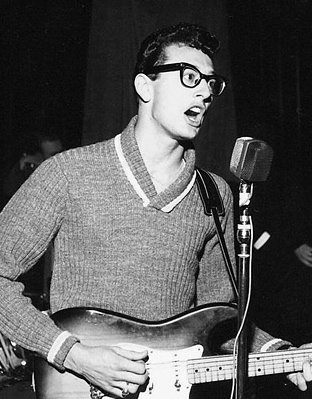

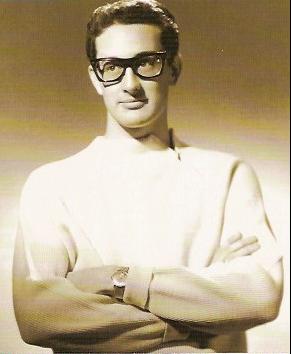

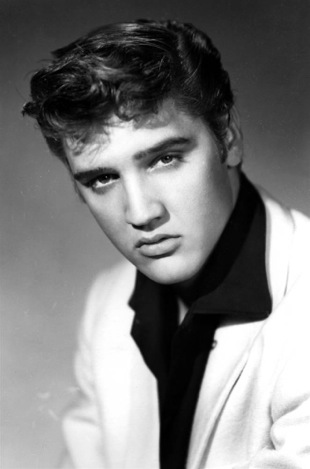

Paul Williams may have been over stating things a bit, but Buddy Holly certainly earned his currently accepted status as one of rock ’n’ roll’s founding fathers in the late fifties. In 1986, Buddy and Elvis Presley were both named charter members of the newly established Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The two men had many other things in common. Both were born in the deep south and raised in poverty. Early contact with country music and rhythm and blues stimulated their youthful, creative musical spirits. There were obvious differences, as well. Buddy looked like the typical boy next door, while Elvis’s smoldering looks oozed sexiness. Holly was an accomplished guitar player and songwriter; Elvis was neither. On stage, Presley’s voice and energy were boundless, while Buddy depended more on instrumentation and his unique “hiccup” vocal style.

Elvis Presley was born on January 8, 1935, in Tupelo, Mississippi. Buddy Holly was born a year and a half later on September 7, 1936, in Lubbock, Texas. Coincidentally, the currently accepted definitive biographies of both men were published a year apart—Peter Guralnick’s Last Train to Memphis in 1994 and Ellis Amburn’s Buddy Holly: A Biography in 1995. Most of the following references to Holly’s life and career come from the Amburn volume.

• Family backgrounds were important

Growing up in the late and post-Depression years, both Buddy and Elvis were “mama’s boys,” due to weak father figures. According to Amburn, “The situation would have far-reaching consequences for Buddy, who would make the mistake of relying on stronger personalities who were not always trustworthy.” Elvis had the same weakness, but fortunately for him the man in whom he put his trust, Colonel Parker, brought Elvis incredible fame and wealth, while Buddy’s manager held him back and stole a fortune from him.

An advantage that the young Buddy had that Elvis lacked was a trusted sibling. The youngest of four children, Buddy found in his eldest brother, Larry, a confidant he would cling to for the rest of his life.

When his other brother, Travis, came home from the war in 1945, he taught Buddy how play the guitar. Around the same time, about 900 miles to the east, Elvis Presley received a guitar for his eleventh birthday and began learning how to play it with help from his uncle and church pastor. A natural affinity for the instrument allowed Buddy’s guitar playing to progress at a rate that amazed his family.

Hank Williams, Sr., was Buddy’s first musical idol. According to Amburn, though, when Buddy first heard Fats Domino sing on the radio, he saw his future. “It was as if the heavens had opened,” Amburn explained. “But it was more than just the music. From that moment on, Buddy identified closely with blacks.” Meanwhile, an adolescent Elvis was experiencing a similar epiphany in Memphis, to where his family had moved in 1948.

Although a year younger, Buddy Holly got started in professional music before Elvis. Around 1951, when Buddy was 15 years old, he started jamming with another Lubbock musician, Jack Neal. The two put together a country and western act and played live entertainment Saturday morning for youngsters at Lubbock movie theaters. In September 1953, “The Buddy and Jack Show” made its debut on KDAV radio. On November 10 that year, a station DJ recorded an acetate of the duo singing and playing. It was just a few months after Elvis had walked into Sam Phillips’s Memphis Recording Service to make an acetate of “My Happiness” and “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin.”

• Buddy the tortoise, Elvis the hare

As rock ’n’ roll became more prominent on the radio during Buddy’s senior year in high school, he and Jack began playing the new music at sock hops, store openings, and community shows. Meanwhile, things were happening much faster for Elvis in Memphis. By the time Buddy graduated from high school in 1955, Elvis already had four singles out on Sun Records and had worked the concert circuit across the south for a year and a half.

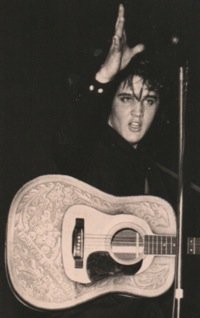

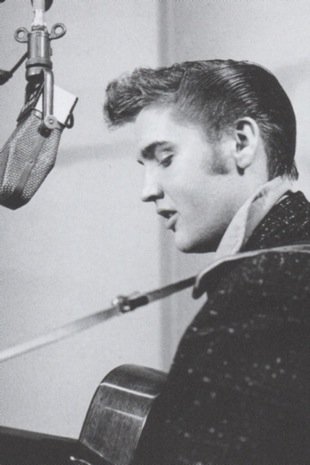

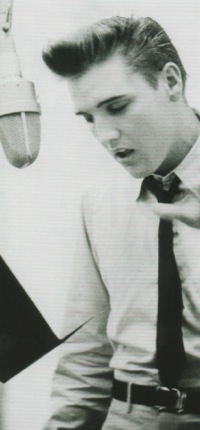

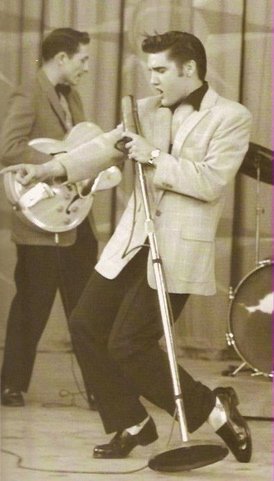

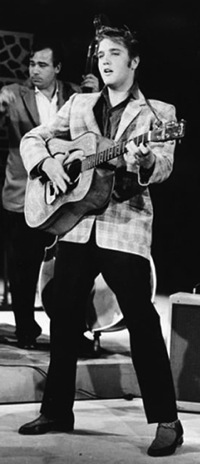

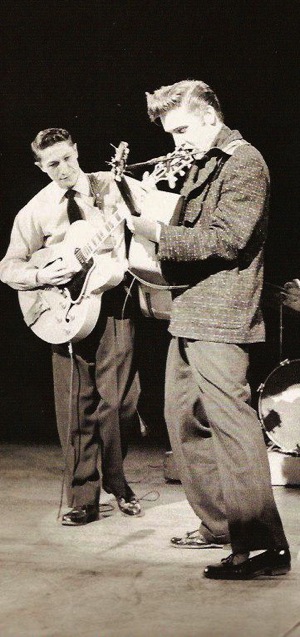

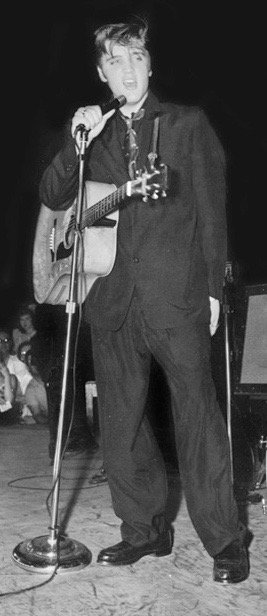

Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly (far right) in Lubbock, June 3, 1955

Everything changed for Buddy when Elvis came to Lubbock five different times in 1955. “What is certain beyond any doubt,” Amburn declared, “is that when Elvis Presley hit Lubbock in 1955, he transformed all the C&W pickers in Buddy’s circle into rockers. ‘Without Elvis,’ Buddy once said, ‘none of us could have made it.’ Though rock ’n’ roll had burst on the world of West Texas the previous year with Bill Haley’s ‘Shake, Rattle, and Roll,’ it was Elvis who whispered freedom into the ears of embattled Baptist boys like Buddy and unleashed a new generation of rockabillies.”

“Elvis changed Buddy,” singer Waylon Jennings, then another young West Texas musician, later told Elvis biographer Peter Guralnick. “It was the beginning of kids really starting to think for themselves, figuring things out, realizing things that they would never even have thought of before.”

Buddy’s brother Larry remembers when Elvis was late for one of his early 1955 appearances at Lubbock’s Fair Park Coliseum. “In Elvis’ absence, Buddy and his front band blew the roof off the coliseum, playing until Elvis came on,” Amburn reported. “Many people in the audience preferred Buddy to Elvis, Larry proudly recalled, although Buddy was still a beginner.”

On October 15, 1955, Elvis appeared at two venues in Lubbock. After finishing up at the coliseum, he gave another show at the Cotton Club, the city’s major dance hall. “We opened for Elvis,” recalled Sonny Curtis. “Bales of cotton were stacked around the stage to protect him from the audience. The most beautiful girls in Lubbock were trying to climb the bales to get at him. That’s what impressed us as much as his music. We’d been hillbillies but after the Cotton Club we were rockers like Elvis.”

• Buddy Holly knew Elvis “quite well”

The extent of Buddy’s personal relationship with Elvis in 1955 is unclear. “Buddy and Elvis got along pretty good,” Larry claimed. “When Elvis came to town, Buddy found him a girl. She was not anyone you’d find on this side of town.” As for Buddy, during his Australian tour in 1958, he told a DJ that he’d once known Elvis “quite well.”

Back in Lubbock in 1955, though, Elvis was clearly Buddy Holly’s idol. Buddy even made a leather guitar case for his J-45 that matched the one Elvis used to carry his Martin D-28. “I Forgot to Remember to Forget,” Elvis’s Sun record that topped Billboard’s C&W chart in late 1955, was Buddy’s favorite Presley song. Late in the year, Buddy and his band performed on "The Big D Jamboree," Dallas’s Saturday night country and western radio show. Sid King, another musician on the show that night, described Buddy as “virtually a carbon copy of Elvis.”

According to Amburn, in 1955 there was another Lubbock visitor who would play an important role in the careers of both Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly. Colonel Tom Parker came to town looking for a talent to manage. Amburn says that both Elvis and Buddy “intrigued” the Colonel, who decided to focus on Elvis. He thought enough of Buddy, though, to recommend him to Nashville talent agent Eddie Crandall.

That led to Buddy’s first big break in show business. When he and his band opened for Bill Haley and the Comets at Fair Park Coliseum in October 1955, Crandall was there to see Buddy. On December 2, Buddy signed an exclusive management contract with Crandall. That was less than two weeks after Elvis left Sun Records and signed a contract to record for RCA. Soon Crandall got Buddy a record deal with Decca.

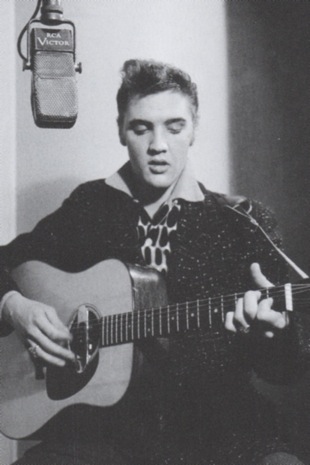

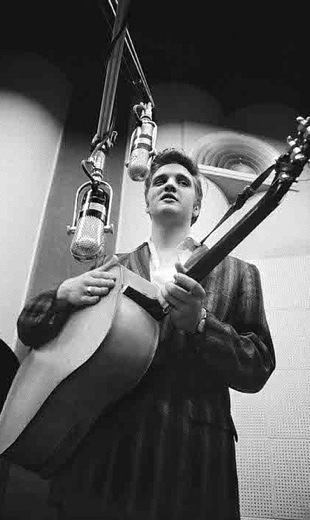

As 1956 dawned, it looked like both singers’s dreams of fame and fortune were about to come true. Both Elvis and Buddy had January dates in Nashville for their first recording sessions for their new labels. While 1956 would turn out to be a spectacular breakout year for Elvis, for Buddy it was a year of failure and exploitation that would test his resolve to make it as a professional entertainer. In RCA’s Nashville studio on January 10, Elvis recorded “Heartbreak Hotel,” which would reach the top of Billboard’s pop chart in May, launching Presley’s fabulous run through the end of the decade. Meanwhile, Buddy’s Nashville Decca session on January 26 was a disaster that led to nowhere.

• Decca a little bit country, RCA a little bit rock ’n’ roll

Amburn explained how differing philosophies at RCA and Decca dictated totally different outcomes for the two young singers. “In the growing conflict between C&W and rock ’n’ roll … country music would be split down the middle, RCA and at least half of the C&W establishment fleeing to rockabilly … and the other half remaining straight country singers.” Some at RCA may have had their doubts, but they allowed Presley to do his thing. “At Decca,” noted Amburn, “Buddy’s mentors would prove less amenable to the new music; in fact, they hated rock ’n’ roll.”

The result was that instead of viewing Buddy as a potential new rockabilly star, Decca tried to force him into the existing country music model. The result was predictable. After Buddy’s first single, “Blue Days, Black Nights” and “Love Me” was released on April 16, it sold only 19,000 copies. “It’s a wonder the world ever again heard of Buddy Holly,” Amburn noted. Buddy’s second release for Decca also failed miserably, and at year’s end the label declined to renew his contract. As 1957 dawned, Buddy was penniless, his career no further along than it had been 12 months before.

The one positive thing Buddy took from his failed year at Decca was some experience with songwriting. For his January 1956 Nashville session, the label asked Buddy to show up with four original songs. One of the songs Buddy wrote and recorded for Decca, “That’ll Be the Day,” came off poorly and was never released by the label.

In January 1957, without a manager, a band, or a recording contract, Buddy returned to Lubbock and considered quitting the music business. Deciding to give it one more try, he formed another band and drove ninety miles northwest of Lubbock to record at Norman Petty’s recording studio in Clovis, New Mexico. There, on February 24, 1957, Holly’s life changed when he recorded a rocking version of “That’ll Be the Day.”

Petty took the acetate to Nashville and got Buddy a one-record contract on the Brunswick label. Amburn called Brunswick, “a kind of trash-basket label in which Decca dumped its undesirables.” “That’ll Be the Day” by the Crickets, the name of Buddy’s new band, was released nationally on May 27, 1957. It spent 22 weeks on Billboard’s Top 100 pop chart, peaking at #3. It reached that same number on Cash Box magazine’s list of “Best Selling Singles.” Buddy Holly had finally hit the big time.

• Buddy Holly's career took off in ’57

He had a lot of catching up to do, however. By the time “That’ll Be the Day” became Buddy’s first hit record, Elvis already had five #1 singles and eight gold records. Holly had two more of his own compositions lined up to follow his first hit—“Peggy Sue” and “Oh Boy,” both recorded at Clovis in July 1957. Both charted in the top 10 late in the year.

Suddenly, Buddy Holly was in great demand. With the Crickets, he appeared three times on American Bandstand and twice on The Ed Sullivan Show. At Christmas time in 1957 Buddy co-starred with Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, and the Everly Brothers on Holiday of Stars Twelve Days of Christmas Show in Times Square. As the new year began, Buddy Holly found himself Decca’s top recording artist.

Like Elvis had in 1956, Buddy Holly spent much of 1957 and 1958 on the road. Unlike Elvis, though, who headlined his own tours, tightly controlled by Colonel Parker, Buddy’s only option was to join the great rock ’n’ roll package tours, organized by promoters like Alan Freed and Dick Clark. “Planned and mounted like military campaigns, these all-star caravans swept across the country in buses,” Amburn explained, “playing as many as 70 cities in 80 nights.” Buddy toured the nation and Canada with other rock stars, such as Frankie Lymon, Gene Vincent, Paul Anka, Jerry Lee Lewis, Eddie Cochran, The Everly Brothers, Connie Francis, The Drifters, Chuck Berry, Buddy Knox, and Danny and the Juniors.

Although Buddy never met Elvis again after their 1955 encounters in Lubbock, their paths almost crossed again in Vancouver, B.C., in the fall of 1957, when both were out on tour. Elvis was there on August 31 for his controversial show at Empire Stadium. Buddy came through eight weeks later with a package tour booked into the Georgia Auditorium. Hall of Fame DJ Red Robinson interviewed both stars prior to their shows. Buddy expressed a longing for a break in the grueling rock ’n’ roll grind. “Enervated from singing his guts out in nightly rock shows,” Amburn explained, “he longed for a radical change in musical trends, confessing that he’d rather sing songs that didn’t require him to scream and shout.”

Elvis and Buddy both recorded their rock ’n’ roll versions of some R&B classics, including “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” “Ready Teddy,” “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” and “Rip It Up.” Although Elvis never recorded a Buddy Holly song, Buddy recorded one of Elvis' from the soundtrack of his 1957 film, Jailhouse Rock. According to Waylon Jennings, Buddy’s version of “(You’re So Square) I Don’t Care” is the best example of the “Buddy Holly sound.”

The package tour format allowed Buddy to perform overseas, something Elvis often expressed a desire to do but never did. In January 1958, Buddy, along with Anka and Jerry Lee, flew out of New York for a tour in Australia. They stopped in Hawaii along the way, where Buddy performed a free show for military personnel at Schofield Barracks, the same venue where two months earlier Elvis had given his final concert of the 1950s. While in Australia, a DJ asked Buddy if Elvis was his favorite singer. “I guess he’s one of them,” Buddy responded. Soon after returning from Australia, Buddy and the Crickets left for England, arriving on March 1, 1958, for a twenty-five-day British tour.

• Rock ’n’ roll’s first wave played itself out

While Buddy was still in abroad, cracks were beginning to appear in his career and in rock ’n’ roll music in general. Buddy’s record sales began to decline. His single releases of “Maybe Baby” and “Rave On,” both considered early rock classics today, stalled at #18 and #37 respectively on the Top 100. “It’s So Easy,” another Holly classic, didn’t chart at all in 1958. Neither of Buddy’s albums reached the Top 40 on Billboard’s album chart. When Alan Freed’s forty-four-day “Big Beat” package tour, which included Buddy, ended with a riot in Boston, it galvanized the societal enemies of rock ’n’ roll to mount an all out war against it. Elvis was taken away by the army, and Jerry Lee Lewis’s career never recovered after it was revealed he had married his 14-year-old cousin.

The only good news for Buddy Holly in the latter half of 1958 was his marriage to Maria Elena Santiago in August. That fall, however, Buddy and his wife left Lubbock and moved to New York City. Buddy had fired his manager, but it was too late. Much of the money he had earned through record royalties and touring was gone, spent or tied up by the man Buddy had trusted to handle his financial affairs. (Reading Ellis Amburn’s account of how Norman Petty mismanaged Buddy Holly’s career should make all Elvis fans say, “Thank God for Colonel Parker.”)

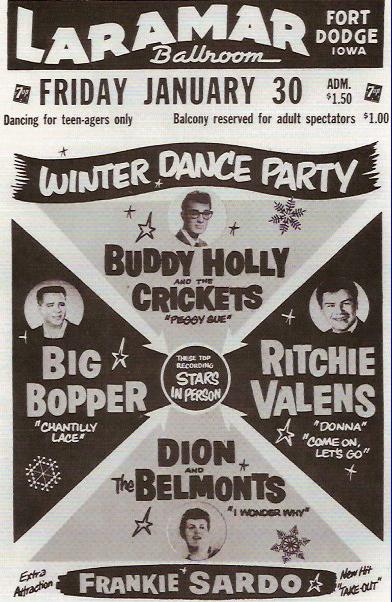

In early 1959, Buddy Holly, with a pregnant wife and living off the generosity of his wife’s aunt, did something he didn’t want to do—he signed on for still another all-star package tour. The “Winter Dance Party” was to be a twenty-four-day meander across the upper mid-West in a converted school bus in the dead of winter. His death at age 22 in an Iowa cornfield plane crash on February 3, 1959, abruptly ended the brief yet brilliant career of Buddy Holly.

According to Peter Guralnick and Ernst Jorgensen in their book, Elvis: Day by Day, Elvis learned of Holly’s death at his army posting in Germany on February 5. The authors state that Colonel Parker’s assistant, Tom Diskin, sent a telegram of condolences to Holly’s family on Elvis’ behalf.

• Death brought fame to Buddy Holly

Recognition as one of rock ’n’ roll’s pioneers, denied him in life, came to Buddy in many forms in death. In addition to being charter members of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, both Holly’s and Presley’s images appeared on U.S. Postal stamps in 1993. Buddy had five entries—“That’ll Be the Day,” “Not Fade Away,” “Rave On,” “Peggy Sue,” and “Everyday”—on Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. (Elvis had 11 on the list.) “That’ll Be the Day” and “Peggy Sue” are on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s list of songs that shaped rock ’n’ roll.

No Graceland exists for Buddy Holly pilgrims. His birthplace in Lubbock was demolished years ago, and in the 1990s, his family sold off their Buddy Holly keepsakes and memorabilia. In Lubbock there is the Buddy Holly Center, inside of which is The Buddy Holly Gallery, a permanent display featuring, according to the center’s web site, “Artifacts owned by the City of Lubbock, as well as other items that are on loan.” Included in the display are “Buddy Holly’s Fender Stratocaster, a songbook used by Holly and the Crickets, clothing, photographs, recording contracts, tour itineraries, Holly’s glasses, homework assignments, and report cards.”

Like Elvis’ fans, the Buddy Holly faithful honor their rock idol by gathering each year on the anniversary of his death. Starting in February 1979, on the 20th anniversary of his death, the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, where Buddy gave his final show on February 2, 1959, has hosted an annual Buddy Holly tribute weekend. The 2013 event is being expanded to four days to accommodate the ever-increasing number of rock ’n’ roll fans who attend. It’s not quite the same as the candle-light vigil at Graceland during Elvis Week, but those who are moved to do so can trek through the snow to a nearby cornfield where a marker memorializes the lonely spot where “the music died” back in 1959. — Alan Hanson | © October 2012

"It was Elvis who whispered freedom into the ears of embattled Baptist boys like Buddy and unleashed a new generation of rockabillies."