Elvis History Blog

A Book Review …

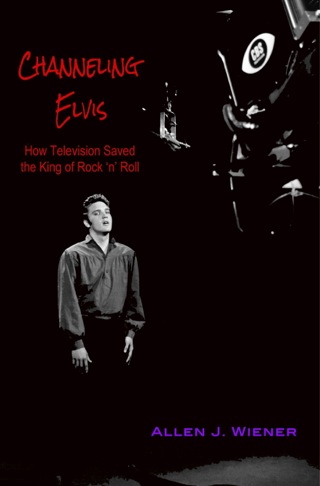

Channeling Elvis

How Television Saved the King of Rock 'n' Roll

by Allen J. Wiener

Since Elvis Presley’s death in 1977, several hundred books have been written about the life and career of the King of Rock ’n’ roll. Scholars, relatives, friends, fans, employees, gurus, and girlfriends all have piled their personal reflections on the mountain of Elvis lore. Only a dozen or so notable volumes, though, deserve inclusion in every Presley aficionado’s library. Allen J. Wiener’s Elvis book is the first in many years to reach that level of distinction. In fact, I can’t think of another book that has expanded knowledge about Presley as much since Peter Guralnick’s Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley was published in 1999.

According to a back cover blurb, Channeling Elvis: How Television Saved the King of Rock ’n’ Roll is “based on more than a decade of research, dozens of fresh interviews, and careful review of hours of television and other footage.” The book certainly has the trappings of a cerebral study. It contains 281 pages of text, followed by 18 pages of endnotes, a 6-page bibliography, a list of Presley video and sound recordings, and a full 22-page index. Listed at the beginning of respective chapters are complete dates, times, locations, performers, and production staffers for each of Elvis’s 17 network television appearances between 1956 and 1977.

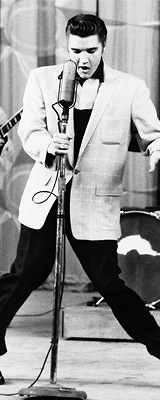

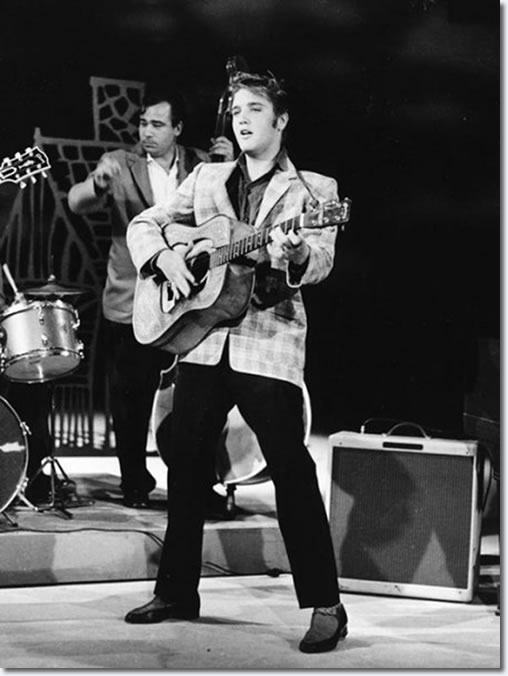

Wiener’s preface, however, quickly dispels some of the studious impression created by the book’s outward appearance. The text has a conversational, almost informal, quality that is maintained throughout. Also, through the use of some embellished descriptive language, Wiener reveals that he is an Elvis fan and not just some detached scholar trying to dissect the Presley phenomenon. The King’s devotees will rejoice when the author declares that, “crowds screamed, cried, and literally went wild at the sight of his physical gyrations and the sound of his emotional delivery.” Examples of such exaggerated hype are scattered throughout the first half of the book.

However, there’s more than enough in Channeling Elvis to satisfy Presley realists and historians. Wiener uses solid sources and annotates the text with nearly 300 footnotes. For dating events and statistical particulars, he relies heavily on the definitive works of Peter Guralnick and Ernst Jorgensen.

At the heart of the book’s content, though, are the dozens of interviews Wiener conducted with people who worked closely with Presley’s TV projects. In his Acknowledgments, the author lists the names of 32 people who responded to his questions. They include Elvis insiders, such as Scotty Moore, D.J. Fontana, and Gordon Stoker, who have spoken about Elvis in the past, and many others who worked either in front or behind the cameras during Presley’s TV appearances. (Wisely, the author chose to exclude the opinions of the guys in Elvis’ inner circle, many of whom have made dubious and contradictory statements in the past. The reliable Jerry Schilling was the only member of the Memphis Mafia interviewed for Channeling Elvis.)

Wiener’s guiding thesis, condensed in the book’s title, is expanded in the preface. “In a single year, Elvis used television to push his career onto one of the fastest tracks in show business history, and he emerged a major international star at the end of it. After that, he would use television far more sparingly, but to equal effect. At several key junctures when Elvis needed to rejuvenate his image or jump-start his lagging career, he turned to television as the vehicle to carry him back to the top, and it rarely failed him.” It’s hardly a startling or original premise. The importance in Presley’s career of his appearances on the Dorsey Brothers show, the Sullivan show, and his 1968 NBC-TV special have long be acknowledged.

What Wiener has done, though, for the first time, is to take a close look at all of Presley’s TV appearances and assess how they affected the course of his career. The author does not ignore the other areas of Presley’s work, however. His personal appearances, recordings, film work, and even his personal life, are treated as part of the context leading up to and between TV appearances. Channeling Elvis, then, is actually a history of Presley’s entire career from 1954 through 1977, with heavy emphasis on his work in television.

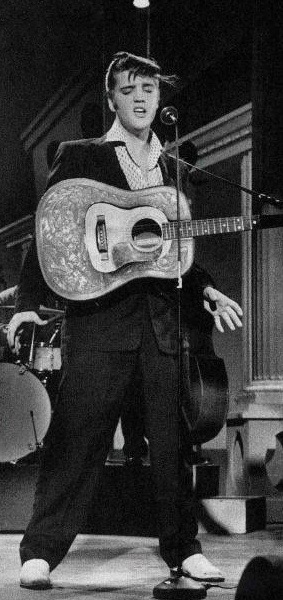

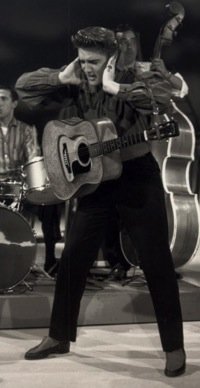

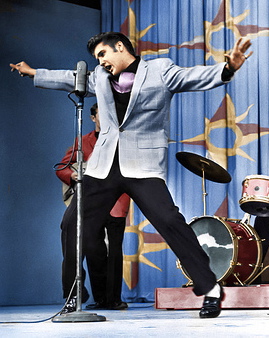

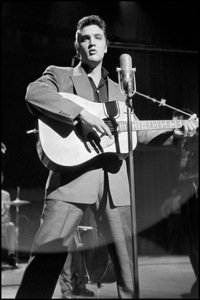

After providing some basic background information about Elvis’ early days at Sun Records in 1954-55 and Colonel Parker’s entrance on the scene, Wiener starts his in depth study of Presley on TV in the 1950s with his six appearances on the Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show in January through March 1956. He then puts the spotlight on Presley’s two appearances on the The Milton Berle Show in April and June that year. Next up for examination is the controversial treatment accorded Elvis on The Steve Allen Show on July 1, 1956. Later that same evening, Presley sat for a short telephone interview on columnist’s Hy Gardner’s network show, Hy Gardner Calling! For the sake of comprehensiveness, Wiener devotes a chapter to this minimal episode on Presley’s TV ledger. The author then provides his own analysis of Presley’s much studied appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show in September and October 1956 and January 1957.

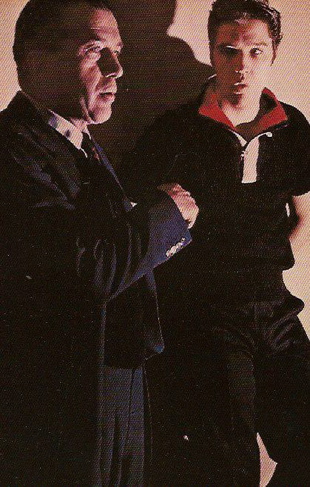

Although Wiener provides interesting information about all of Presley’s TV appearances in the 1950s, the most absorbing scrutiny is given to Elvis’ treatment on The Steve Allen Show. For dressing Presley in a tuxedo and having him sing “Hound Dog” to a basset hound, Allen has been roundly criticized by Elvis fans through the years for humiliating the singer. In long passages from an interview with Steve Allen before his death, Wiener allows the host to defend himself, putting a new perspective on the incident nearly six decades later. Also, interview comments by Skitch Henderson, Allen’s orchestra conductor in 1956, add even more depth to this new look at one of the most contentious events in Presley’s life. “We were so stupid not to assimilate what was happening in the business,” Henderson admitted years later.

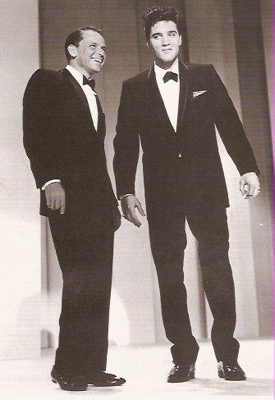

Wiener then transitions to Presley’s next TV appearance on The Frank Sinatra Timex Show, which aired on ABC in May 1960. More interesting than the frivolous content of the show is the author’s impression of what the two pop music icons thought of each other. Of particular interest is the description of an incident in which an angry Sinatra confronted Colonel Parker and threatened to fire “that hillbilly” after Parker demanded more money for Elvis' appearance.

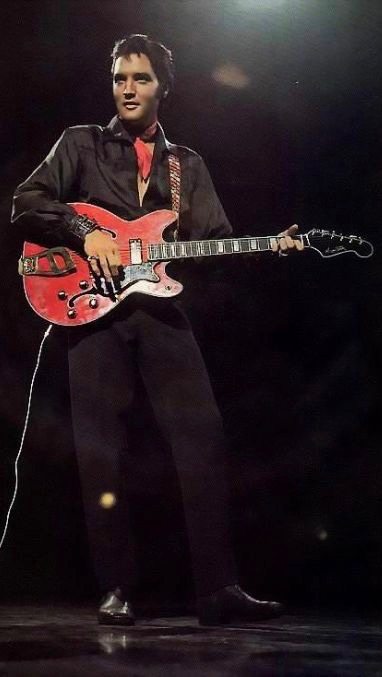

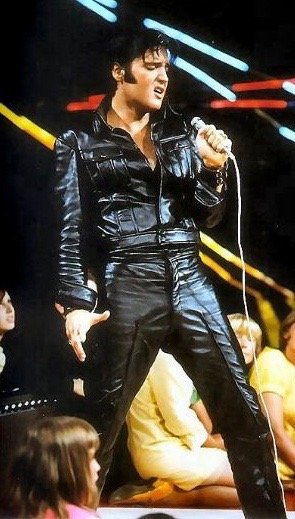

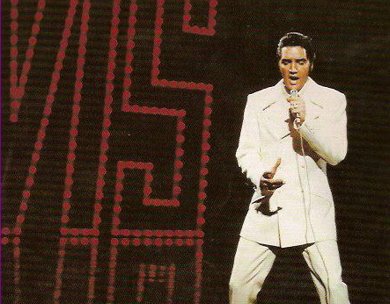

After hastily dismissing Presley’s “lame recordings and less-than-stellar movies” in the mid-’60s, Wiener arrives at Elvis’ singular television event, the 1968 “Comeback Special” on NBC. Wiener is at the top of his game here, devoting four chapters and 50 pages to an event he unabashedly labels “one of television’s most memorable moments.”

The author paints a fascinating picture of how the special came together. The production was a team effort by director Steve Binder, executive producer Bob Finkel, musical director Bones Howe—all of whom are quoted liberally in the text—and Elvis Presley. Despite having to battle obstruction from NBC censors, corporate sponsors, and Colonel Parker, Binder’s team produced an hour-long broadcast that fit Wiener’s thesis perfectly—it revived Elvis Presley’s career, which had been on life support in Hollywood and on the record charts.

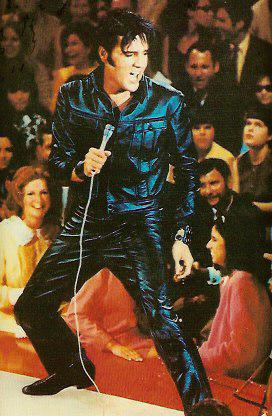

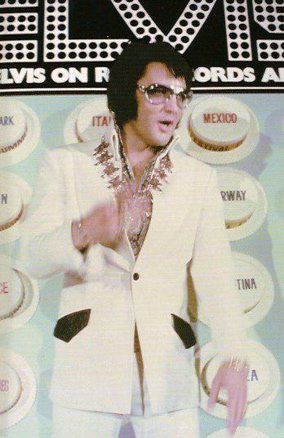

Wiener acknowledges that by the time of Presley’s next TV appearance, the 1973 Aloha from Hawaii concert, Elvis had squandered most of the momentum gained from his “Comeback Special” four years earlier. In fact, the author spends much time in this section portioning out blame for the disappointing final product. Elvis gets some, but the majority of culpability is assigned to producer-director Marty Pasetta. In fairness, Wiener gives Pasetta plenty of opportunity to present his side of the story.

From the moment I began reading Channeling Elvis, I knew that a piece of vital evidence relating to the quality of the author’s research awaited me in the section on Elvis’ Aloha from Hawaii broadcast. Would the author give credence to the often-stated but absurd myth that over a billion people saw Presley’s Aloha show in 1973? To Wiener’s credit, he reported the truth:

“The Colonel and RCA could not resist gilding the lily with some over-the-top claims, the most laughable being that the special was viewed by somewhere between 1 and 1.5 billion people. A simple check of population figures alone in the countries that received the special shows the estimates to be ridiculous.”

The author continues telling the truth in the final three chapters of Channeling Elvis. With brutal honesty, he recounts how drug use and boredom destroyed Presley’s career and took his life. For Elvis fans this section is difficult to read. There is precious little compassion for Presley in the book’s closing pages, which extend beyond his death to describe the singer’s final TV appearance, the woeful Elvis in Concert, broadcast on CBS on October 3, 1977, seven weeks after his death.

Despite its inevitable sad conclusion, Allen Wiener’s Channeling Elvis is an entertaining and informative read. Its many interviews reveal new perspectives on Presley’s life and career, no mean accomplishment considering the multitude of books that have been written about him since his death nearly four decades ago.

Along the way there are many amusing and thought-provoking anecdotes to be remembered long after the book’s final page is turned. There’s Jordanaire Gordon Stoker labeling one of Elvis’ biggest hit records, “a stinking piece of material.” And Bob Finkel having to send assistants out on the streets of Burbank to round up an audience for Elvis after Colonel Parker forgot to hand out the tickets. And Presley’s piano player, Glen D. Hardin, openly blasting as incompetent two other members of Elvis’ seventies stage band. There’re just a few of the many entertaining side stories to be found in Channeling Elvis. — Alan Hanson | © October 2014

"At the heart of the book’s content are the dozens of interviews Wiener conducted with people who worked closely with Presley’s TV projects. They include Elvis insiders Scotty Moore, D.J. Fontana, and Gordon Stoker."