Elvis History Blog

Colonel Parker and Hal Wallis Controlled Elvis’ Films in ’60s

While Elvis was out of the spotlight in the army from 1958-1960, Colonel Parker designed and refined the strategy he would use with Hollywood studios on Elvis’ behalf throughout the sixties. He had already figured out how he could play Paramount, MGM, and 20th Century Fox against each other. Starting with the salary he got for Elvis from one studio, Parker would demand an increase in his negotiations with the next studio. That higher salary, then, would become the starting point for the next contract, and so on.

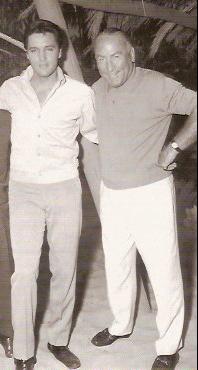

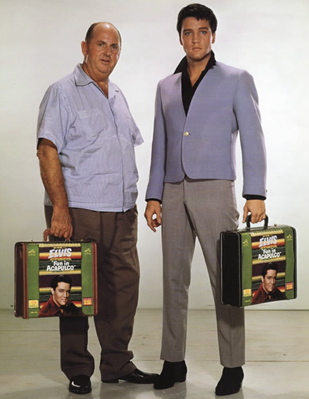

Soon after Elvis entered the army, Parker began twisting Hal Wallis’ arm. The Colonel knew Wallis (with Elvis at right) was counting on producing Elvis’ first post-army movie, but Parker wasn’t about to let Wallis get away with paying his client the paltry $25,000 allowed under the existing 1956 contract. The producer gave in, and in a new contract, finalized in October 1958, Wallis agreed to pay Elvis $175,000 for his first post-army film, plus a percentage of the profits.

The very next day, Colonel Parker, citing the $175,000 Paramount agreed to pay, got Fox to sign a new deal paying Elvis $200,000 and $250,000 for two pictures (Flaming Star and Wild in the Country) plus 50 per cent of the profits. Throughout the ’60s, Parker used the same tactic to steadily increase Presley’s Hollywood income.

• Colonel Parker’s “hands-off” policy

From the beginning, though, Colonel Parker had decided that once a contract was signed, neither he nor Elvis had the right to interfere with the production side of any picture the studio wanted to make. “There’s no sense in sending me the script,” Parker informed Buddy Alder, when the Fox executive offered to send the Colonel the script for The Reno Brothers. “The only thing I’m interested in is how much you’re gonna pay me.”

Parker openly admitted he had no expertise in the movie-making business. When Flaming Star producer David Weisbart asked the Colonel’s input on picking a director, Parker replied, “I would not know whether you would need a sensitive director, even if I had read the script, as this is not one of my qualifications.”

In a 1964 Variety article, Parker coldly explained his hands-off policy on studio production decisions for Presley movies. “We don’t have approval on scripts — only money. Anyway, what’s Elvis need? A couple of songs, a little story and some nice people with him. We start telling people what to do and they blame us if the picture doesn’t go. As it is, we both take bows and if it doesn’t hit maybe they get more blame than us. Anyway, what do I know about production? — nothing.”

And the Colonel counselled Elvis, as well, not to question studio decisions. In a 1995 book, Presley confidant Marty Lacker claimed that Parker told Elvis not to upset Hollywood people. “You do everything they say,” Lacker paraphrased Parker. “If you’re going to sign a contract, you do exactly what they want, no matter what they do to you. If you do anything wrong, they’ll ruin your career and you’ll go back to being just a poor kid again.”

• Parker’s policy called a “criminal waste of talent”

Of course, if the Colonel did instruct Elvis to meekly accept all decisions made by his producers and directors, as Lacker contends, then Parker’s role in killing Elvis’ dream to be a good dramatic actor is magnified. Obviously, Elvis needed a separate adviser in this area. If Parker knew nothing about movie production, which he admittedly didn’t, then Presley needed a consultant who did.

In the 1971 radio documentary, The Elvis Presley Story, actor and producer Jack Good condemned Parker’s hands-off policy on the production side of Elvis’ films. “I think it’s a strange policy and almost an inhuman policy,” said Good. “I can’t understand how anyone can have the guts to take that attitude. And I think the results have been very successful commercially but artistically it’s been a criminal waste of talent.”

There was, however, one element that the Colonel fought to have included in every Presley movie — music, and plenty of it. Parker had seen how Elvis’ four movies in the fifties had spawned number one selling singles and albums. Biographer Alanna Nash described the Colonel’s movie/music formula as follows: “Elvis’ movies would promote the soundtrack albums, and the single from the soundtrack would publicize the film. It was an ideal commercial equation.”

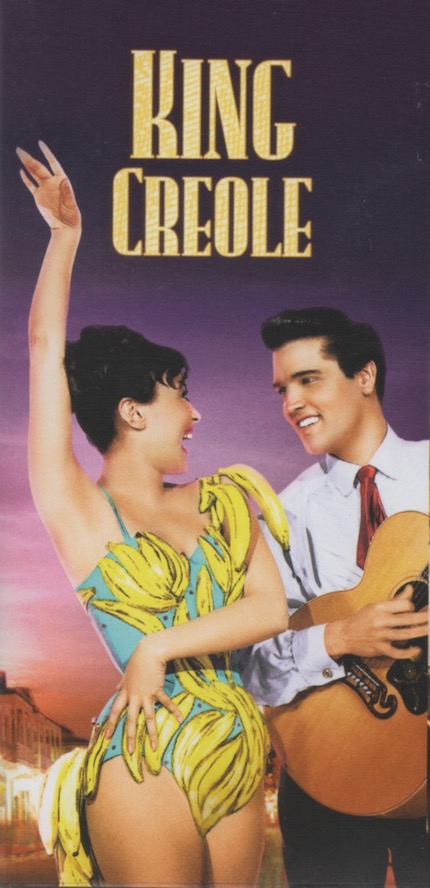

King Creole proved to be a rare example of how a serious acting role could be combined with Elvis singing on screen. However, even when it was obvious that such a combination wouldn’t work in every film, Parker continued to pressure the studios to include music. In 1960, Flaming Star director David Weisbart insisted, “I cannot see how it is possible for Elvis to break into song without destroying a very good script.” The Colonel didn’t care. “We want all the best possible results for this picture,” he told Weisbart, “including the hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of exploitation represented by a good record release by Elvis.”

Weisbart then had director Don Siegel insert several Presley vocals into the narrative. However, when a test audience laughed during one music scene, it was pulled from the final cut. In the end, only the title tune and one country ditty appeared in Flaming Star.

• Three turning points key in Elvis’ career

The fundamental question concerning Elvis Presley’s Hollywood career is: “How did the character and quality of his films evolve?” That question can be answered by examining three key turning points in the early sixties.

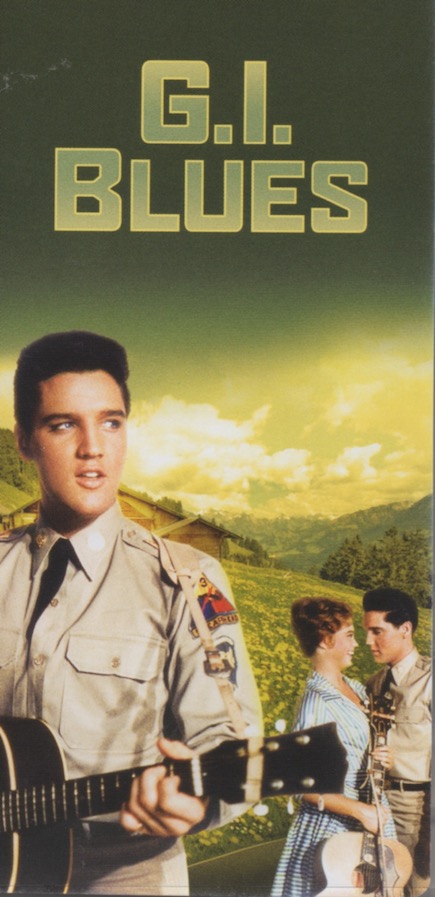

The first involves comparing Presley’s two post-army films made in 1960 — G.I. Blues and Flaming Star. The former was a light-weight musical comedy, made under the Hal Wallis formula at Paramount. The latter was a dramatic Western with little music produced by 20th Century Fox. The two films were released within a month of each other in late 1960. The box office comparison was one-sided. G.I. Blues finished 14th on Variety’s list of the year’s top grossing films, while Flaming Star came in far down the list. Obviously, moviegoers favored Elvis the singer over Elvis the actor.

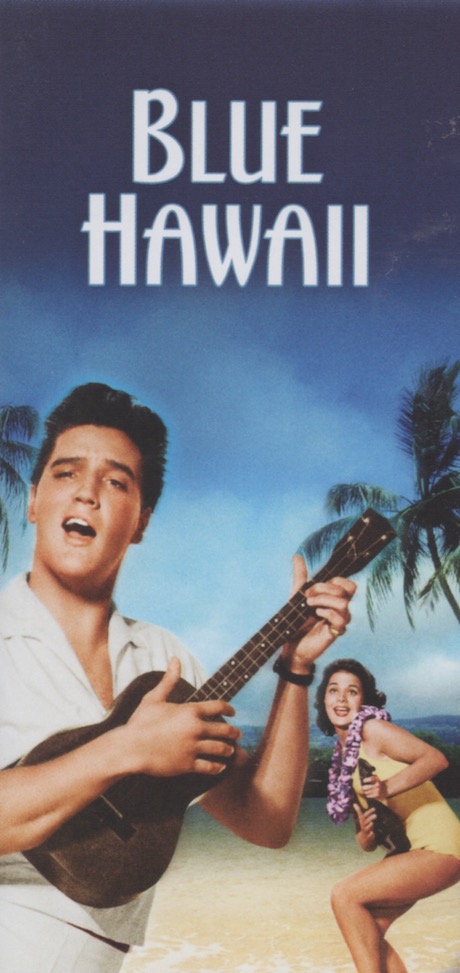

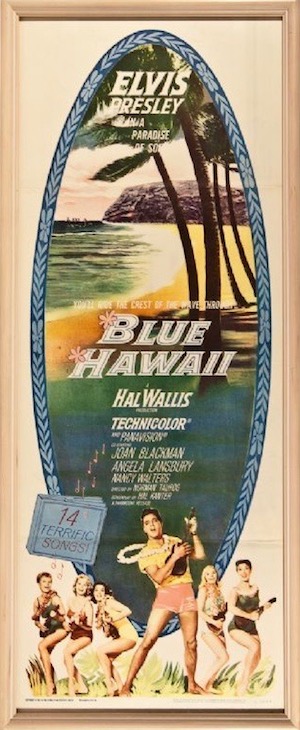

The second turning point in Presley’s career came the following year, when Blue Hawaii, another Paramount song-filled romp, did even better at the box office (10th highest grosser in 1961 and 14th in 1962) than G.I. Blues. Completely eclipsing, as it did, Elvis’ other 1961 film, the drama Wild in the Country, Blue Hawaii solidified Presley’s role in Hollywood as a musical comedy performer. Studio producers and the movie-going public alike lost all interest in seeing Elvis in dramatic roles thereafter.

Elvis, himself, apparently abandoned his dream of becoming an accomplished dramatic actor. He accepted the reality of his film career in a 1962 article in Parade Magazine. “I’m smart enough to realize that you can’t bite off more than you can chew in this racket. You can’t go beyond your limitations … A certain type of audience likes me. I entertain them with what I’m doing. I’d be a fool to tamper with that kind of success. It’s ridiculous to take it on my own and say I’m going to appeal to a different type of audience, because I might not. Then if I goof, I’m all washed up, because they don’t give you many chances in this business.”

The third turning point came in 1964, when the expected high profits from MGM’s Viva Las Vegas were diminished by production cost overruns. Parker, seeing that such overruns threatened Presley’s profit sharing income (and his own), insisted on tighter budgets and shorter shooting schedules to keep future film costs down. The initial result was MGM’s Kissin’ Cousins, followed by a dozen more cheap musical comedies, which led to Elvis henceforth being considered, in the words of director Don Siegel, as “kind of a joke in the industry as an actor.”

• Fike called Colonel’s formula the “correct” one

Parker is normally assigned the majority of the blame for the deterioration of Elvis’ film career in the mid-1960s. Interestingly, though, one of the Colonel’s defenders was long time Presley friend and confidant, Lamar Fike. Harboring an intense personal dislike of Parker, Fike nevertheless endorsed the manager’s movie policy while fixing most of the blame on Elvis in Revelations of the Memphis Mafia in 1995.

“This isn’t a very popular view, but Colonel’s formula was correct. The serious stuff — the movies that didn’t have many songs in them — flopped. That’s a pretty good argument. On the other hand, by the time Elvis figured out he was being screwed around, it was too late. He signed too many contracts. If the Colonel handed him a contract, he’d sign it and never look at it … And when you’ve already been paid for the pictures, and you’ve already spent half the money, you’ve got to do them. All those pictures were presigned. So Elvis had no choice.”

In fairness to Colonel Parker, although his demand for leaner budgets was a major factor in the deterioration of Presley’s films after Viva Las Vegas, he did try to improve the situation. After viewing the first cut of Harum Scarum in 1965, Parker sent a letter to MGM criticizing the picture’s quality and suggesting that more time be spent filming the next picture to get a better result.

And Nash reported that by 1967, “the Colonel had been rethinking his strategy, trying to find projects to challenge Elvis.” He tried but failed to get Elvis a nonmusical role in his last movie with Wallis at Paramount. That same year, Parker wrote to MGM: “I sincerely hope that you are looking in some crystal ball with your people to come up with some good, strong, rugged stories.” Finally, late in 1967 the Colonel’s deal with National General Pictures included a commitment by the studio to feature Elvis in a straight dramatic role (Charro!).

• Fans, Elvis, Parker, and Wallis all share responsibility

Ultimately, then, with whom lies the responsibility/credit/blame (take your pick) for the progression of Elvis Presley’s film career? First and foremost on the list is Elvis’ movie-going public during his Hollywood years. Many fans today are convinced Elvis could have been a fine dramatic actor if only his handlers hadn’t prevented it. The fact is that Presley’s fans of the ’50s and ’60s flocked to see Elvis sing on screen, not to see him act. Ticket sales determined what future Presley’s films would look like.

Next in line was Elvis himself. He had a laundry list of fatal flaws — lack of backbone, misplaced loyalty, lack of commitment, desire for wealth. He could have fired his manager at any time and surrounded himself with competent advisers. He could have placed his dream ahead of accumulating wealth. He chose not to. No excuses.

Colonel Parker comes next. He worked hard to make Elvis a star and maximize his income, but he took advantage of Elvis’ weaknesses to gain complete control of his client in an industry that Parker admittedly knew little about. He had the arrogance to believe that he should be Presley’s sole counsellor in financial and professional matters. He was wrong.

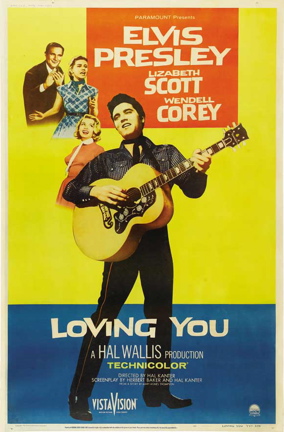

Finally, Hal Wallis convincingly demonstrated that Elvis Presley’s appropriate role in films was that of a musical entertainer, not as an actor. In the end, other studios were forced to accept Wallis’ unwavering assessment of Presley. There was no vanity in Wallis’ actions, however. He accepted Elvis as he was and wound up making Presley’s most critically acclaimed film (King Creole) and his most commercially successful one (Blue Hawaii).

• Elvis’ “star quality” remains despite movie career

Ultimately, though, one has to wonder why Elvis’ body of film work is lamented by so many of his fans today. Certainly he made some good films, and, as his friend Marty Lacker pointed out, Elvis’ musical career rose above his Hollywood years. “Even though most of the later pictures hurt his reputation as an actor, they hadn’t tarnished his star quality,” Lacker noted. “Everybody still wanted to meet him and be around him, and that included other stars.” And the half million people who pass through Graceland each year attest to Elvis Presley’s star quality today as both an actor and a singer. — Alan Hanson | © 2012

"Obviously, Elvis needed a separate adviser in this area. If Parker knew nothing about movie production, which he admittedly didn’t, then Presley needed a consultant who did."