Elvis History Blog

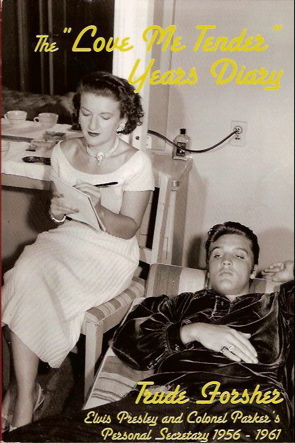

Hollywood Secretary Trude Forsher

Was Col. Parker’s Biggest Booster

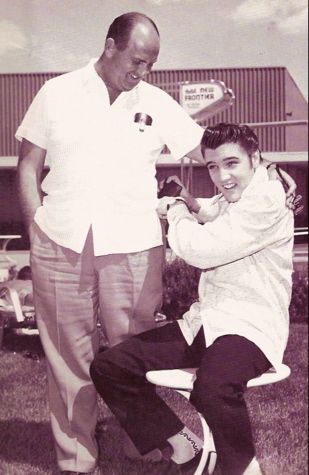

When it comes to Elvis Presley fans, you’d be hard pressed to find a handful of Tom Parker admirers. Presley loyalists have long and loudly blamed the Colonel for nearly every misstep in Elvis’ professional and personal life. Oh, there are some Parker apologists out there. I’ve defended him at times, and I know Gordon Stocker respected the Colonel for his fair treatment of the Jordanaires through the years. But an outright champion of Tom Parker? I’d never heard of one—until now.

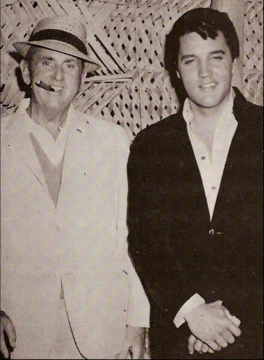

In 1956 Trude Forsher was a stay-at-home housewife and mother. After an appearance on Groucho Marx’s You Bet Your Life TV program, Trude’s article about that experience appeared in TV Radio Life magazine. That started a chain of events that led to her becoming Colonel Parker’s secretary in Hollywood. A friend introduced her to Parker, who granted her an interview. The Colonel then allowed her to interview Elvis immediately following his appearance on The Milton Berle Show in June 1956. The following month, Parker hired Trude to be his and Elvis’ secretary at 20th Century-Fox during filming of Presley’s first movie, Love Me Tender. She served in the same capacity when the Presley entourage returned to Hollywood for the production of Loving You and Jailhouse Rock in 1957 and King Creole in 1958.

After Trude Forsher died in 2000, her son James edited her diaries and memoirs from the Hollywood years and published the portions relating to Colonel Parker and Elvis in 2006 under the title The “Love Me Tender” Years Diary. In that volume, she repeatedly voices her unabashed admiration for both of her employers. There is nothing unusual about her high regard for Elvis. Many people who knew and worked with Presley in those early Hollywood years similarly praised him. However, the esteem she expressed for Colonel Parker is unparalleled for a man who has been roundly savaged through the years for his handling of Elvis’ career.

• Trude learned life-long lessons from the Colonel

“I want to speak of what it was like working for the Colonel and the lessons I learned from him, and in understanding people, about the power and promotion,” she stated in her memoirs written in 1977. “These lessons influence my life to this day.”

Her wholehearted respect for the Colonel’s character and professionalism is somewhat startling for those of us who are used to Parker being vilified on both fronts. “I always respected the Colonel’s personal values: loyal to his friends and associates, kindhearted, and helpful to newcomers,” Forsher declared. “His word in business, as well as to a friend, is as good as a bond.”

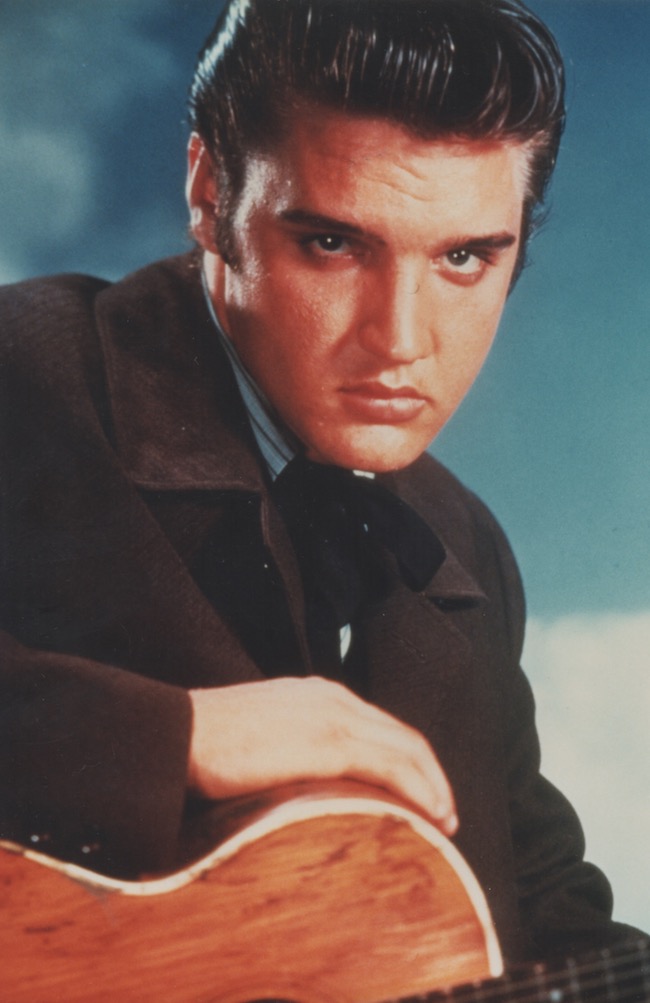

To Trude her employer was bigger than life, an inspiring American success story. “Colonel is a self-made man. His is one of the greatest Horatio Alger stories of all time,” she asserted in her memoirs. “His brilliant mind and sense of humor and a show business touch were generally recognized as surpassing even P.T. Barnum. He was the force that created Eddy Arnold and other stars before I met him. And then he discovered Elvis.”

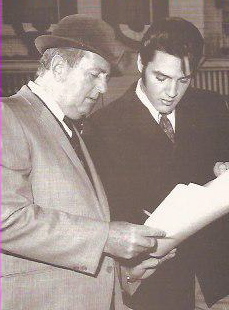

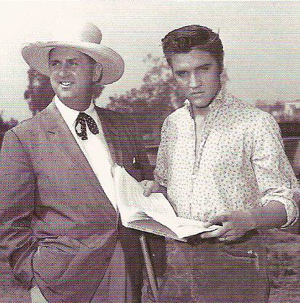

Here Forsher begins to wade into the controversy over the amount of credit Parker deserves for Presley’s sudden rise to stardom in the late 1950s. In her memoirs, Trude repeatedly expressed high praise for Elvis’ talent, but, as the following exchange with Parker reveals, she was convinced he never could have risen so high without the Colonel’s help.

"One day … I said: “Colonel, I understand all this excitement; Elvis has magnetism …” The Colonel looked at me seriously, giving each word of mine its full due, and replied: “Magnetism—if I hadn’t taken him off the truck, with all his magnetism, he would still be driving truck …” That sums it up, naturally, Elvis’ great, unique talent was a prerequisite, but in Hollywood talent is not enough—the secret is presentation, promotion, publicity, business know how—all that adds up to showmanship. And Colonel Parker is by general consensus the greatest showman of them all."

• Colonel Parker fed his secretary a “snow job”

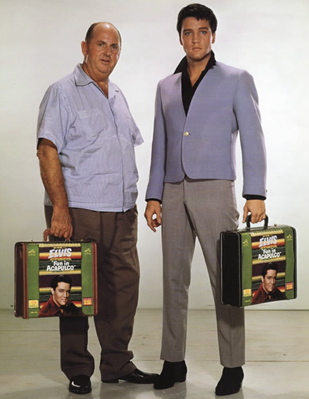

Keeping in mind that there are a number of passages of questionable accuracy in Trude Forsher’s memoirs, if Parker really claimed that he had taken Elvis “off the truck,” then he was clearly overstating his importance in starting Presley on the road to success. According to Ernst Jorgensen and Peter Guralnick’s chronology, Elvis: Day by Day, Colonel Parker first saw Elvis perform on January 15, 1955, when Presley appeared on The Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Clearly Presley’s professional career was already on the rise before Parker first came on the scene. Elvis had already made 46 public appearances in four states, as well as eight previous appearances on the Hayride and one at Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry. He had a recording contract with Sun Records, and his first two single record releases had been reviewed in Billboard magazine. Furthermore, Elvis had quit his truck driving job at the Crown Electric Company sometime in October 1954, three months before the Colonel first saw him. In claiming that he took an unknown truck driver and created a national entertainment phenomenon, Parker was clearly feeding his secretary one of his famous “snow jobs.”

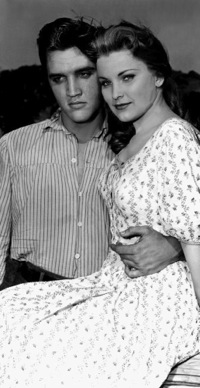

Trude Forsher saw the Parker-Presley connection as a partnership in which both were equally responsible for the success that came their way. “Much has been written about the relationship of Elvis and the Colonel,” she noted. “During my years with them it was a most congenial one. The Colonel ran the office with a literally around-the-clock promotional effort, and Elvis devoted his efforts to personal appearances, recording sessions, [and] films … Many of the young stars of the 1950’s lost their box-office value almost as quickly as they attained fame. Elvis never had such a worry. The Colonel worked around the clock to promote him, to keep Elvis on top, to increase his fame and box office appeal … It was fortunate for Elvis that he completely trusted the Colonel’s judgment in guiding his career, and thus he was protected from all kinds of pressures other young personalities and stars must deal with.”

According to Forsher, the Colonel was besieged in the late fifties by many artists who wanted Parker to manage them. He remained dedicated to Elvis, though. “His answer,” Forsher says, “always was, ‘Thank you, I can’t accept. I manage only one artist, Elvis.’”

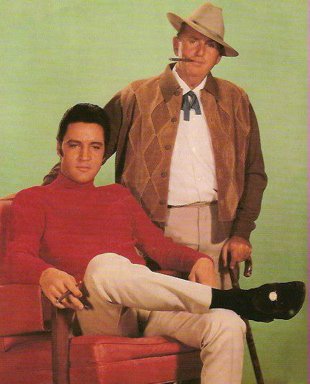

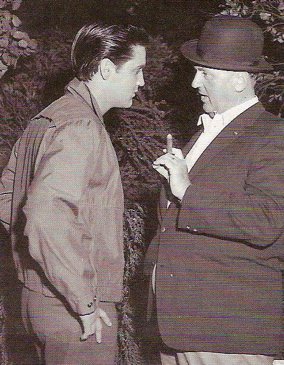

• The Colonel demanded equal consideration for all

Colonel Parker has often been accused of arrogant behavior with those he judged to be subordinates. His secretary observed none of that. Just the opposite, in fact, as she revealed in the following passage from her 1977 memoirs.

"To the Colonel, one person is as important as another. When we worked in the movie studios, I was at first greatly impressed when the top executives came to my office for pictures and souvenirs, and I told the Colonel about my feelings. To my surprise, he was not pleased about my enthusiasm and told me that every person was equally important, and I was to pay just as much attention to a carpenter, the guard at the gate, a movie extra, as to a vice president. And this was the Colonel’s approach … for all the years I worked with him and Elvis."

Most of Trude Forsher’s secretarial duties ended when Elvis finished his work on a film, and he and Colonel Parker cleared out their studio offices and headed back to their Tennessee homes. Forsher recalled with melancholy those days of parting with her two employers.

"Sometimes the Colonel, no doubt remembering his circus days when a picture was finished, said, 'Let’s fold up the tents.' Yes, being with Elvis and the Colonel was for me truly the greatest show on earth. There was the ever-present challenge of the new, but to me, there was a little sadness every time we folded up the tents and left our temporary “homes.”

• Employer-secretary relationship ended, but not the respect

Between films Trude served as Colonel Parker’s west coast helper. She took care of correspondence and any other Hollywood business that came up. In preparation for Elvis and the Colonel’s return to Hollywood, she would arrange for and prepare offices and dressing rooms at the studios.

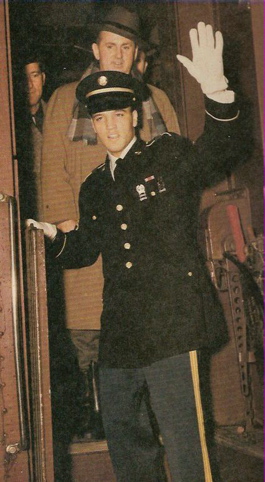

Despite her requests, Parker did not allow her to write freelance articles about Elvis. In late 1957, she wrote to the Colonel offering to go on tour with Elvis without pay. He curtly replied that women were not appropriate companions on tour. When Elvis entered the army soon after the filming of King Creole in 1958, her contact with Colonel Parker slowly faded away. However, to the end of her life 42 years later, Tom Parker never had a more loyal supporter than his first Hollywood secretary, Trude Forsher. — Alan Hanson | © December 2011

Go to Elvis History

Go to Home Page

"Her wholehearted respect for the Colonel’s character and professionalism is somewhat startling for those of us who are used to Parker being vilified on both fronts."