Elvis History Blog

Fan Mags Kept Elvis Home Fires

Burning During the Army Years

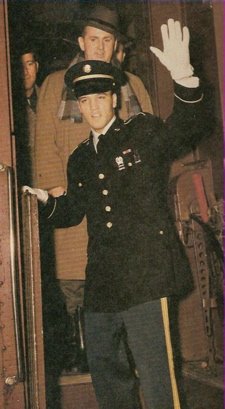

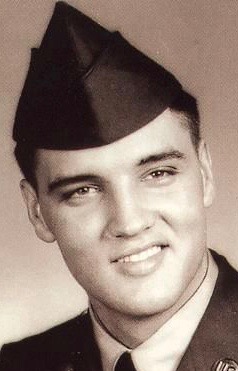

With the exception of one recording session, after Elvis Presley’s army induction on March 24, 1958, his show business activities halted completely for nearly two years. His handlers, though, worked tirelessly to keep Presley’s image alive in the marketplace. Although Elvis was out of sight, his fans still had one more opportunity to see him perform. King Creole, produced just before his induction, wasn’t released in theaters until three months later. When Elvis embarked for Germany in the fall of 1958, however, he physically disappeared from the entertainment landscape.

His recording label did what it could to keep his voice alive at home. While Elvis was in uniform, RCA issued 5 Presley singles, 3 LPs, and 6 EPs. While they did well on both the record charts and in the record stores, they were not enough to meet Colonel Parker’s goal of keeping Elvis continually in the public eye during his absence.

Part of Parker’s strategy was to promote Presley in the nation’s popular celebrity magazines. Encouraging writers to cover Elvis cost the Colonel nothing and led to regular articles about Elvis appearing in various entertainment publications that were trendy with Elvis's young demographic.

Just one example is Maxine Block’s article, “When Elvis Comes Marching Home … ” in the November 1959 issue of Movieland and TV Time magazine. Colonel Parker’s prompting was evident immediately in Block’s opening. She quoted Parker: “When that little ol’ boy o’ mine—Elvis Aron Presley—comes marchin’ home again to Hollywood, I aim to give him the biggest ol’ welcome-home party this town’s ever seen. That blowout will be the biggest combined clambake, catfish fry, dancin’-in-the-streets affair you ever heard tell of. The boy deserves it: His record as a GI couldn’t be better and there’s every indication he’ll have more fans than when he left.”

The Colonel fed Block a few Elvis rumors to spread. The singer has his manager scouting out digs for him near Hollywood, Block dutifully informed her readers. Real estate agents were already scouring Westwood, Pacific Palisades, and the San Fernando Valley to find a palatial estate for Elvis, whose army discharge was just five months away. Oh, and Parker had plans as well to send his boy on a nationwide concert tour interspersed with guest shots on TV shows. (Of course, this was all Parker propaganda. He had no intention of harming his client’s movie box office potential by overexposing him on stage or on TV.)

• The “Coke set” was not about to forget Elvis

Block then backtracked to March 24, 1958, which she labeled “Black Monday” for much of America’s female population. “That was the day Elvis Presley traded his blue suede shoes for U.S. Army combat boots,” she reminded her readers. “And there were those who said he’d be forgotten long before he could slip back into his well-worn blue suedes. They reasoned that the Coke set, notoriously fickle, would desert their hero for a new idol … You know the old adage—out of sight, out of mind."

Others had been groomed to take his place, she noted—Rick Nelson, Frankie Avalon, Fabian, Bobby Darin, and Tommy Sands. The truth was, Block contended, “no one has taken the place of the greatest teenage idol of all time.” (Colonel Parker couldn’t have said it better.)

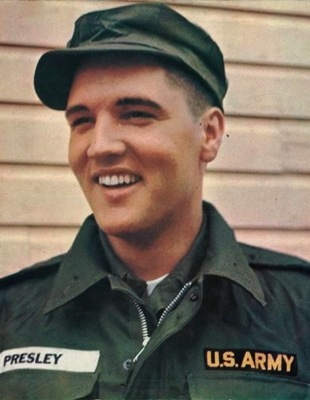

Next came more propaganda from Parker, who, when it came to Elvis, had a fondness for making big numbers even bigger and a shameless proclivity for exaggeration. “In Germany Elvis has received between 5,000 and 10,000 letters a week from fans all over the world,” Block wrote, echoing the Colonel. “The hysteria over the handsome singer has never simmered down. Wherever he’s gone in Germany there’s been a crowd of adoring German teenagers in full cry. They’ve crashed cordons of military police, upset photographers’ cameras and shoved each other in their zeal to press flowers upon him.” (Of course, the truth is the army had kept Elvis away from any such potential disturbances.)

Block went on to assure Elvis’ fans that he wanted to see them as much as they wanted to see him. He was “painfully homesick,” she noted, and he became teary-eyed when he expressed hope he could return home for Christmas on furlough. (Instead he consoled himself with showgirls during a two-week leave in Paris.)

• Elvis was eager to get back to his “American chicks”

Colonel Parker assured Block that the dreams of millions of American girls were still alive. Elvis wasn’t about to fall for any German girl, he said. “It’s this reporter’s feeling that all the talk about Elvis’ finding a real heart interest in Germany is—just so much talk,” Block concluded. Those German girls mentioned in press reports were “merely dates, as are others, with whom he whiles away his few free hours on weekends.” Elvis was looking forward, Block believed, to turning in “the buxom, blond-banged German frauleins for his little ol’ American chicks.”

Maxine Block concluded her article in Movieland and TV Time with the following declaration of Elvis Presley’s enduring popularity.

“Elvis has changed as he’s ripened into manhood, mellowed as he’s shaken hands with maturity and kissed his rebellious adolescence good-bye. So there remains no doubt that he will be a stronger entertainment figure than ever before. His old, loyal audience hasn’t left him—and a good proportion of newer, more mature people will applaud the newer, more mature Elvis Presley.”

(Block’s article must have brought a smile to the face of Colonel Parker, the self-acclaimed “great snowman.”)

• Parker deserves credit for promoting soldier Elvis

That the magazine’s glorification of Elvis in its November 1959 issue was part of an ongoing policy is confirmed in the letters column of the same issue. “MOVIELAND AND TV TIME is my favorite magazine,” wrote Sharon Fox of Chicago. “Why? Because you always have such wonderful stories on Elvis Presley. Other magazines either have him engaged to every girl he dates or even make up stories about him. But we Elvis fans can always rely on MOVIELAND AND TV TIME to give us great stories on our boy.”

Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of such articles appeared in celebrity magazines during Presley’s army hitch. They're just one indication of how Elvis’s manager worked tirelessly during those years to keep his client’s image prominent in the nation’s pop culture. Without Parker’s efforts, would Elvis have come back to civilian life as triumphantly as he did? I think not. — Alan Hanson | © April 2012

Go to Army Elvis

Go to Home Page

"Encouraging writers to cover Elvis cost the Colonel nothing and led to regular articles about Elvis appearing in various publications that were trendy with Elvis's young demographic."