Elvis History Blog

Elvis Presley & Chuck Berry:

Connections and Disconnects

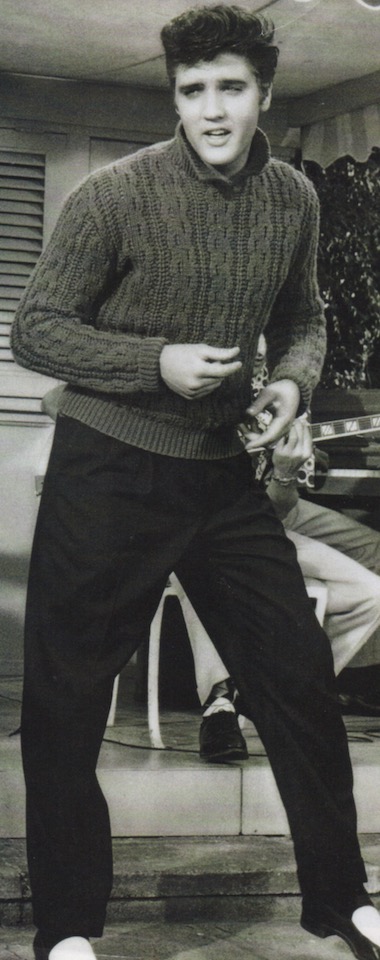

“Before Elvis there was nothing.” | John Lennon

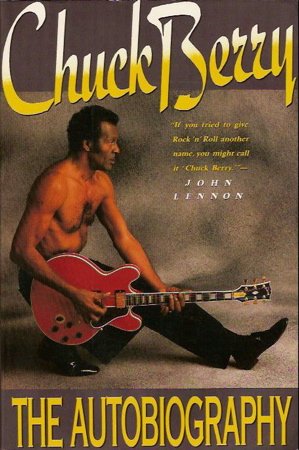

"If you tried to give rock ’n’ roll another name, you might call it ‘Chuck Berry.’” | John Lennon

Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry, as rock ’n’ roll’s two greatest practitioners in the 1950’s, are irrevocably connected in the history of popular music. And yet, between the two great pop music icons there exists a great disconnect as well, something that goes beyond the racial concerns that were so primal in the fifties. In Berry’s 1987 autobiography, Elvis’ name is mentioned only once in passing. And other than as a songwriter, Berry’s name rarely appears in the multitude of Presley biographies and tell-all books.

The truth is that the lives of Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry had both noteworthy similarities and differences, and in their professional careers they at times traveled both parallel and divergent roads.

The story of Elvis Presley’s youth from his birth in Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1935 through his teen years in Memphis is well known. Chuck Berry’s youth was similar in some respects; different in others. In 1926 he was born into a poor family in St. Louis. Like Elvis, Berry sang in a church choir. The setting was quite different, however. Berry formed a Baptist vocal quartet while in prison for auto theft in 1944. He was paroled on his 21st birthday in 1947. The following year he married, and by 1952 he was the father of two daughters.

After his release from prison, Berry started performing at bars and parties, playing guitar and singing popular songs of the day to both white and black audiences. In 1952 he made his first paid nightclub appearance at Huff’s Garden in St. Louis. That led to a booking at the Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis, where his “career took its first firm step,” according to Berry in his autobiography.

In 1954, while he was honing his craft at the “Cosmo,” Elvis Presley made his historic first recordings 283 miles down the Mississippi River in Sam Phillips’s Memphis studio. The following year, Berry drove to Chicago and introduced himself to Leonard Chess of Chess Records. The producer liked the sound of Chuck’s home recordings. Chess suggested that Berry come up with an original tune, and when the singer returned to the Chess studio on May 21, 1955, he was ready to record a hillbilly tune he wrote, called “Maybellene.”

• Chuck Berry’s “Mabellene” a national hit in 1955

If Leonard Chess was Chuck Berry’s Sam Phillips, then DJ Alan Freed was his Dewey Phillips. When Freed, the country’s most prominent rock ’n’ roll jockey in 1955, played “Maybellene” on his New York radio program, the tune rose quickly to the top of Billboard’s national rhythm and blues chart. (Elvis obviously liked Berry’s record, as he sang “Maybellene” in concert and on the Louisiana Hayride often in 1955 and 1956.) Road bookings at prestigious clubs came flowing in, and Chuck Berry’s career started to build momentum.

Berry’s music in 1955 had much in common with Elvis’s. “‘Maybellene’ was my effort to sing country-western, which I had always liked,” Berry noted in his autobiography. At the same time, Elvis was touring with mostly country acts, and his recording of “I Forgot to Remember to Forget” became his first national #1 record, topping Billboard’s country & western chart in 1955.

At Chess Records, Berry admired r&b artists like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Bo Diddley, but he, like Elvis, refused to let himself be locked into one kind of music. At the “Cosmo” in 1954, he played mostly hillbilly and swing music. “It was my intention,” he explained, “to hold both the black and the white clientele by voicing the different kinds of songs in their customary tongues.”

While Elvis was touring the country with Grand Ole Opry stars in 1955, Berry became a lead act in Alan Freed’s traveling rock ’n’ roll troupe. And, like Elvis, Chuck signed on with a manager to handle his bookings and finances. However, while Colonel Parker handled Elvis’ finances successfully and honestly, Chuck Berry was not so fortunate with his management. First, he learned that Alan Freed had not pushed “Maybellene” solely out of love for the record. Freed required, and received, co-writer credit on the song. It wasn’t until 30 years later that Berry finally got back full rights to “Maybellene.” (Of course, at the same time, Colonel Parker was running the same scam in reverse by demanding Elvis receive co-writer credit on songs like “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Love Me Tender.”)

Then, when Berry learned profits were being skimmed from his personal appearances, he fired his manager. For the next 30 years, with only the help of a private secretary, he managed his own career. (Despite the criticism Colonel Parker received through the years, Elvis Presley obviously had neither the business acumen nor the inclination to take such hands-on control of his career.)

• For Chuck Berry there were racial hurdles to clear

Unlike with Elvis, racial discrimination was a major career obstacle that Chuck Berry had to negotiate in the music business of the fifties. In 1956 some of Berry’s publicity photos were purposely underexposed to make his skin color appear much lighter. The intent was to increase chances for bookings, but the trick backfired at times. A club in Knoxville booked Berry, thinking he was white. When he showed up at the door on the night of the show, he was turned away from the whites-only club, even though a sold out audience was waiting inside to see him perform.

“It would be hard to conceive of a white performer attempting the same thing,” author Bruce Pegg wrote in his 2002 Chuck Berry biography. “Elvis Presley may have become successful—like other white performers, before and since—by imitating black performers, but never once would he have felt it necessary to change his appearance and pass for black. For Chuck Berry, however, such racial ambiguity was necessary if he, like Presley, was to cultivate a white audience.”

• Did Chuck Berry owe Elvis a debt of gratitude?

In their book Elvis: His Life From A to Z, Fred Worth and Steve Tamerius suggest that Chuck’s ignoring Elvis in his autobiography, “says something about Berry’s ego.” Their inference, of course, is that Chuck Berry should have acknowledged his debt to Elvis. In Reflections of the Memphis Mafia, co-author and Elvis crony Lamar Fike stated as follows the generally accepted belief among the Elvis faithful that all rock ’n’ roll singers in the fifties, especially the black ones, owed Elvis a debt of gratitude:

“What happened was, in pop music, except for Pat Boone and Bill Haley, the business had been controlled by older singers—Tony Martin, Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, Tony Bennett. Elvis kicked the door open, and for the first time, young people had their own music. Elvis was the musical counterpart to James Dean—he gave that generation voice. Then Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee, who had been regional acts, broke loose nationally, and the Everly Brothers, and Ricky Nelson, and Bobby Darin followed. Rock ’n’ roll was in full swing.”

Of course, this view ignores the fact that Berry had a national hit with “Maybellene” in the summer of 1955, six months before Elvis even recorded “Heartbreak Hotel.” It’s understandable, then, that Berry would find it hard to concede that Elvis broke down a door that he had already opened himself. Rather than giving a single white singer the credit for popularizing rock ’n’ roll, Chuck Berry gave it to the young, post-war white music audience. “It seems to me,” he noted, “that the white teenagers of the forties and fifties helped launch black artists nationally into the main line of power music.”

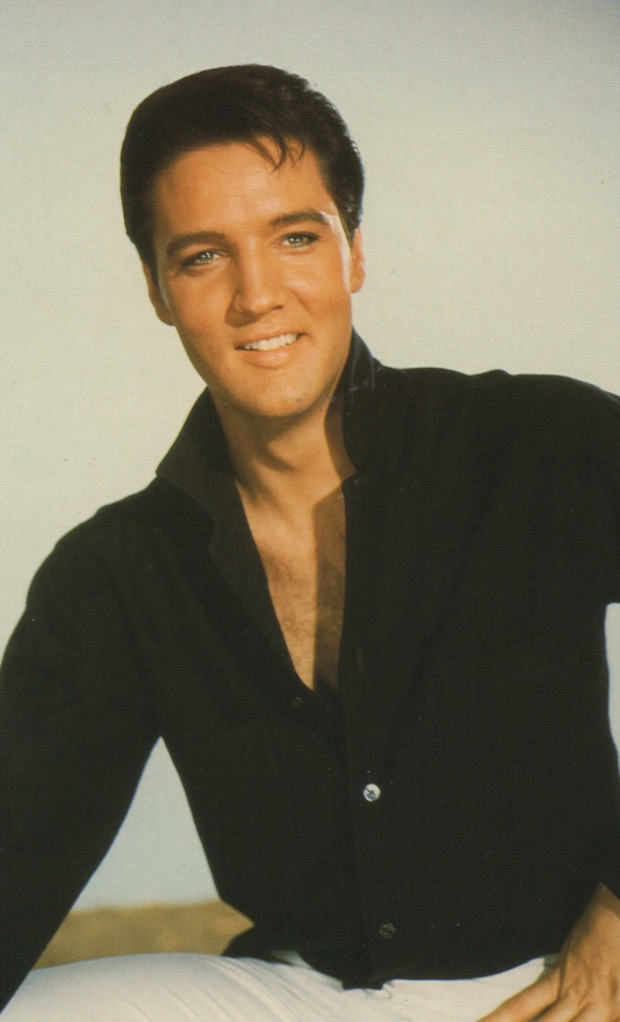

Still, there’s no doubt that Chuck Berry understood that Elvis Presley blazed a trail of musical fame that he wanted to follow. According to biography Pegg, “Looking back at the year in the Chess studios that December (1957), Berry must have believed that success on the scale of Elvis Presley’s was now his for the taking … Small wonder, then, that 1958 would become his annus mirablis, cementing his place once and for all in the pantheon of twentieth-century entertainers and musicians.” Indeed, Berry placed eight recordings in the Hot 100 in 1958, making it the most successful year of his career.

• The year the music died for Chuck Berry

Chuck Berry’s star started to fade in 1959, however, as the “Bobby’s” and “Frankie’s” began to take over the pop charts. And in the early months of 1960, his career, along with his personal freedom, suffered a severe set back. On the same day in March when a newspaper article announced Elvis’ discharge from the army, Chuck Berry was on trial for violating the Mann Act (transporting an underage girl across state lines for immoral purposes). Convicted and sentenced to three years in a federal prison (he served 19 months), Berry spent his hard time writing songs to record when he was released.

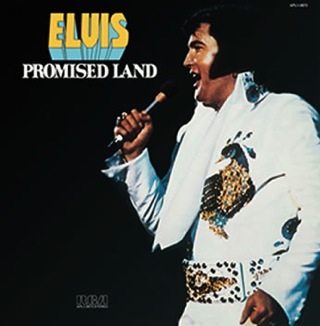

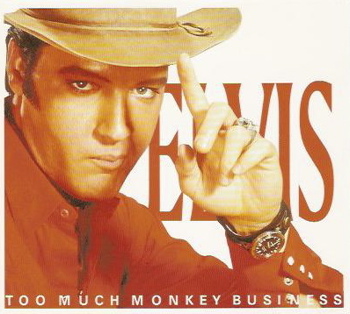

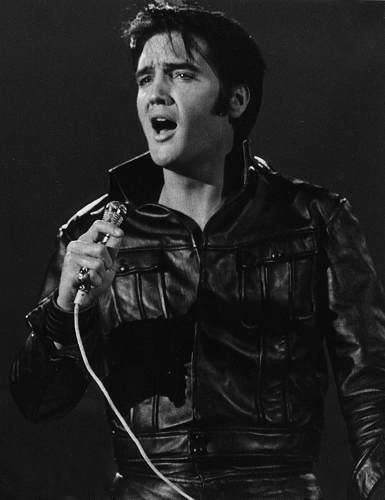

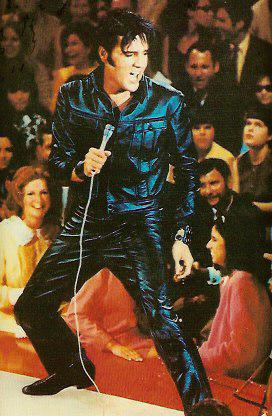

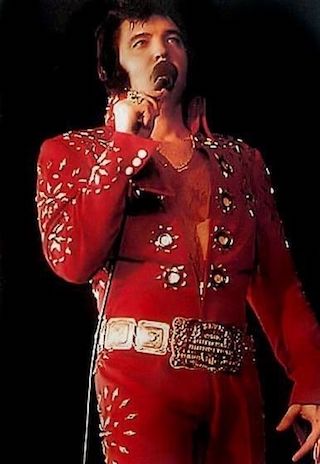

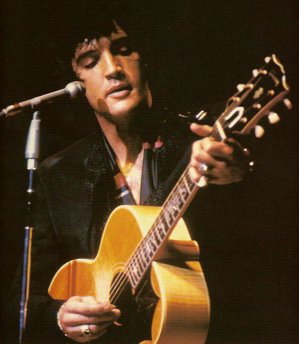

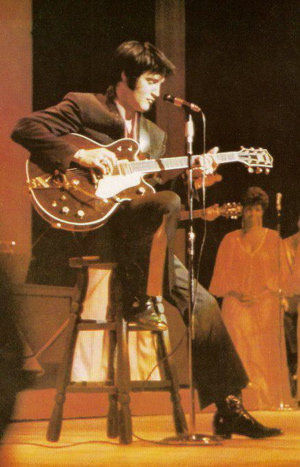

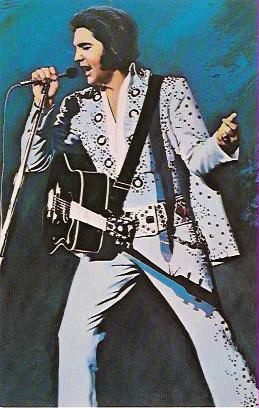

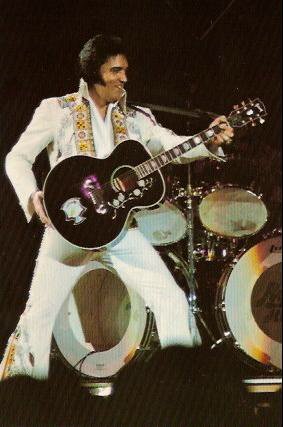

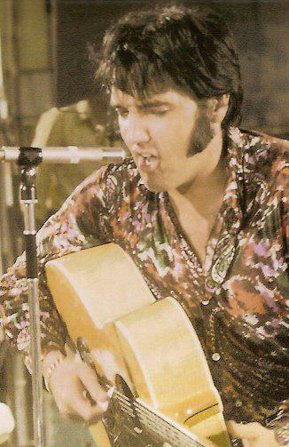

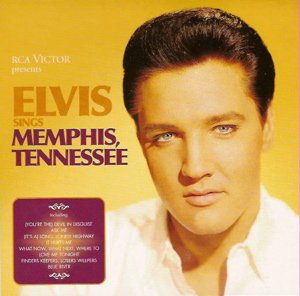

While Elvis’ musical career began to slide in 1963, Chuck Berry emerged from prison and tried to get his own career back on track. There was some success at first—five chart records in 1964 (including “Promised Land,” which Elvis would record 10 years later)—but soon thereafter he dropped off the charts completely for seven years. While Elvis transformed and revitalized his career by returning to to the stage in the late sixties, Chuck Berry kept his career alive by playing dates in clubs, bars, and Vegas lounges.

• Elvis and Chuck crossed paths in Las Vegas

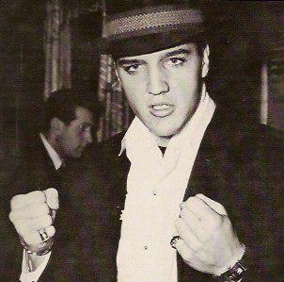

In was in one of the latter that the only known encounter between Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley took place in 1972. Musician Billy Peek, who was working with Berry at the time, recalls suddenly seeing Elvis in the wings watching Chuck’s show at the Hilton:

“He was dressed to the nines, he had the cape, he had the whole nine yards. He was with his wife at the time, Priscilla Presley; then he comes back the following night with his wife and he’s got Sammy Davis, Jr., with him. So he came two nights to watch Chuck Berry play. It was a pretty big nod to Chuck. I mean you could tell he was enjoying it. Chuck was trying to get him to come up and sing one, but he wouldn’t do it. But that was one of the big highlights at the time.”

Coincidently, that same year Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley converged at the top of the Hot 100 with each singer’s final hit record. On October 28, 1972, “My Ding-A-Ling” became Chuck Berry’s only #1 record, with Elvis’ “Burning Love” right below at #2. It was an appropriate chart-topping meeting of rock ’n’ roll’s old guard. Chuck Berry was 46 and Elvis was 37. — Alan Hanson | © April 2011

Go to Elvis History

Go to Home Page

"There’s no doubt that Chuck Berry understood that Elvis Presley blazed a trail of musical fame that he wanted to follow."