Elvis History Blog

Did Elvis Blindly Follow

Where Colonel Parker Led Him?

“I have read several of your observations about Col. Parker and Elvis’ relationship and agree with many, but I have a little different take on some things.”

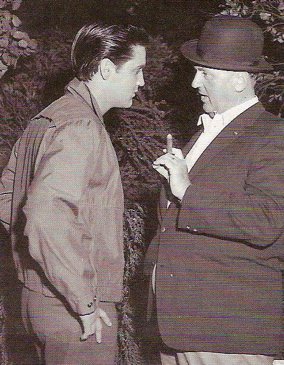

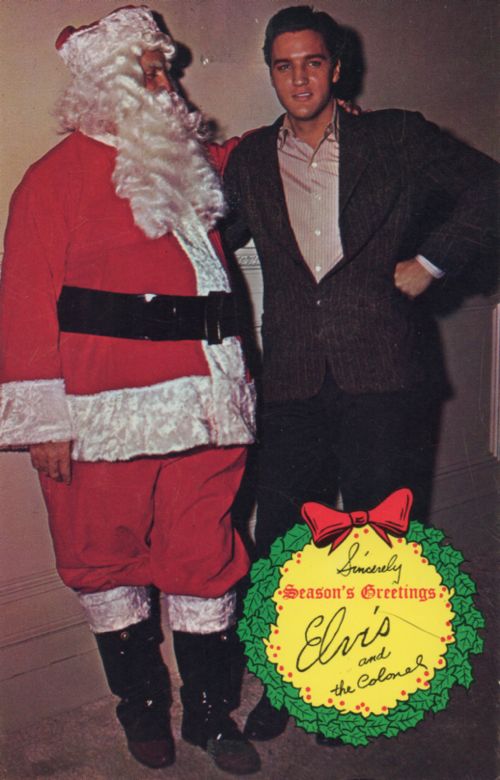

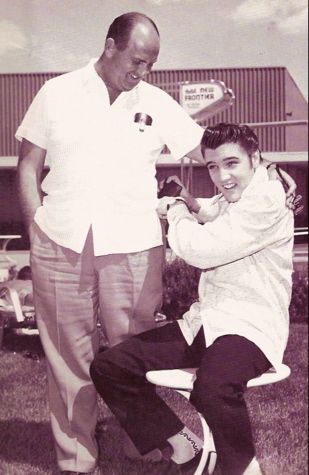

That’s how Ken prefaced a lengthy commentary he recently sent me through elvis-history-blog.com. I have posted four separate articles on the site concerning the Parker-Presley partnership, and they all support my general feeling that the Colonel should not be held responsible for many of the missteps in Elvis’ career. Ken disagrees. “I do see Parker as much more at fault for the direction and ending Elvis had than even Elvis himself,” he contends.

Ken and I share a similar Elvis life experience. We both became fans in 1962 and have read extensively about Elvis ever since. Along the way, however, we have developed differing conclusions concerning Colonel Parker’s role in Elvis’ career. The following discussion is based on our varying points of view.

Ken: Parker was like a Stealth Bomber—he was a quick study of people. After that quick study he knew how to approach that individual and exactly what buttons to push to help bring about a given result, and they had no idea it was being done. The Colonel saw early that Elvis was insecure about most everything except his music. He saw uneducated parents in Vernon and Gladys … what more did he need to see in order to control Elvis in a fashion which kept Elvis doubting his ability to survive in the world of big time business/entertainment without Parker calling the shots?

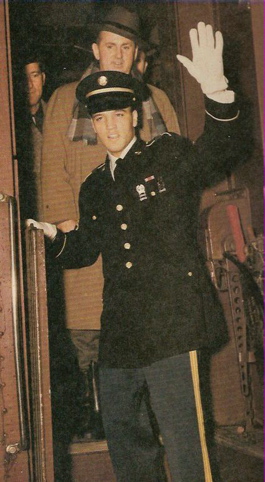

Alan: I agree that Colonel Parker wanted sole power to “call the shots” about Elvis’s career, and that some of those calls turned out not to be in his client’s best interest. However, I don’t believe Parker intentionally set out to play on Elvis’ insecurities to control him. In the beginning, the Colonel saw in Elvis great talent, not insecurity, and his goal was to make Elvis famous and wealthy. He certainly did that in the ’50s. In fact, I can’t identify a single misstep Parker made in managing Elvis in those early years, unless you want to question how Elvis was marketed in Hollywood.

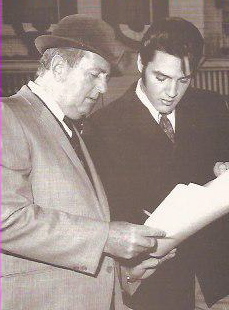

Ken: The film career is a great example. Someone sold Elvis a bill of goods in the start about the direction of his new career. In interviews he talked of not singing in films; he talked of his first picture as being “The Rainmaker.” He seemed excited at the prospect. Either Wallis, Parker, or both must have led him to that belief during the process that led to the seven-picture deal. Let’s face it. The long-term movie contracts and the neglect of the music was a horrid management decision that Parker sold to Elvis as the “correct path.”

In ’65 Parker should have seen that Elvis needed to make a career correction, yet he negotiated more movie deals without asking for better properties, attempts at more quality drama, or even some creative control. Then he sold Elvis on signing them.

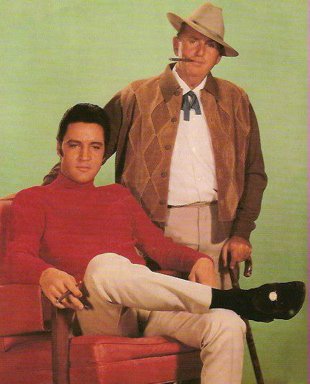

Alan: It’s true that in the beginning Elvis envisioned for himself a career as a serious, non-singing movie star in the mold of James Dean or Marlon Brando. However, in hindsight that dream was certainly unrealistic. Elvis came to Hollywood as a rock ’n’ roll star, not a trained actor. Hal Wallis saw Elvis as a screen draw for teenagers, as a replacement for the Martin and Lewis box office attraction he had just lost.

It wasn’t Colonel Parker, but Elvis’ young fans who rejected him as a serious actor. Consider his first four movies after leaving the army—G.I. Blues, Blue Hawaii, Flaming Star, and Wild in the Country. The first two were big box office hits, while the other two made only modest profits. By 1961 it became clear that Elvis’ appropriate role in Hollywood was in musical romantic comedies. Elvis came to that conclusion himself. In a 1962 interview, he said, “A certain type of audience likes me. I entertain them with what I’m doing. I’d be a fool to tamper with that kind of success. It’s ridiculous to take it on my own and say I’m going to appeal to a different type of audience, because I might not. Then if I goof, I’m all washed up, because they don’t give you many chances in this business. If you’re doing all right, you better keep at it until time itself changes things.”

The long-term contract was a Parker strategy to maximize Elvis’ income in Hollywood. The Colonel often renegotiated the contracts along the way to increase Elvis’ salary. In addition the Paramount and MGM pacts usually contained options for Elvis to do films for other studios, such as when he did Tickle Me for Allied Artists.

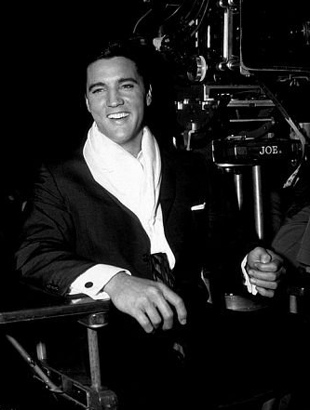

The Presley movie strategy of the ’60s had two flaws. First, making three films per year led to overexposure and poor quality. Second, Parker’s belief that TV and personal appearances would hurt Elvis’s movie box office take was misguided. Still, in the end, Elvis signed all of the movie contracts willingly. He could have said no to any one of them.

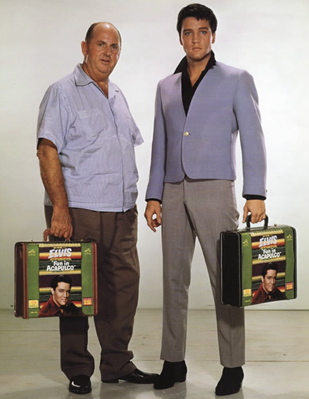

Ken: Parker did not fully understand talent. He did not understand the creative spirit nor the challenge it is to keep them alive and flourishing. He understood money, manipulation and how to use both. Money was the be all and end all with Parker, and he was shortsighted in his management.

Did Parker ever suggest and really push Elvis toward goals beyond money? Acting lessons? Better quality songs? Better scripts? No, he never did, but he did put up barriers such as insisting upon all songs Elvis did going into publishing companies that secured money into the Parker/Presley pockets. After 1962 this practice should have been dropped totally. Parker is considered by some to be the pinnacle of managers, yet he convinced Elvis to give away his pre-’73 music for what amounts to a pittance, and Parker got more of that money than Elvis. [It] is almost universally seen as the worst deal in music history.

Alan: In the ’70s, Parker clearly enriched himself at Elvis’ expense, and some of his actions in doing so are indefensible. There’s no telling how much money Elvis earned for him that Colonel Parker tossed away at the crap tables in Vegas. However, by all accounts, Elvis was no wiser in dispensing his money. His wasteful spending on extravagant gifts, cars, airplanes, and the like brought him to near financial ruin. His need for more cash led to Parker selling his music royalties to RCA for a lump sum. And it was Elvis’ need for income more than the Colonel’s in the 1976-77 period that resulted in an unhealthy Presley working himself to death on the concert circuit.

Was Colonel Parker the kind of manager Elvis needed? Well, yes and no, in my opinion. Parker was the perfect manager for Presley in the fifties. Using TV, Hollywood, and a vigorous personal appearance schedule, the Colonel quickly raised Elvis to phenomenal stardom. I’m not sure any other manager could have done that. Later, though, in the sixties, I have to agree with Ken that Colonel Parker failed his client. Elvis should have fired him and found another manager who could have brought some balance and fulfillment to his career—some movies, some TV specials, some personal appearances, some better music choices. I’m just not sure Elvis had the personal courage to make the necessary changes, whoever his manager might have been. I’ll give Ken the final word.

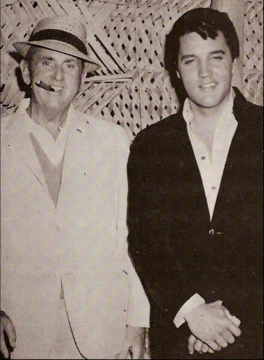

Ken: I do believe Parker loved Elvis, but not enough to allow him to make his own decisions without the stealth treatment. Parker wanted control with no outside interference … hence the Leibers and Stollers, the Binders, the creative people who might sway Elvis were kept at arm’s length most of Elvis’s career by Parker. How would Elvis the artist have grown and profited by having been encouraged to interact with creative people in films and music rather than be warned of their motives? | Alan Hanson | © February 2012

Go to Elvis History

Go to Home Page

"Did Parker ever suggest and really push Elvis toward goals beyond money? Acting lessons? Better quality songs? Better scripts?"