Elvis History Blog

Elvis’ Two Trips to Houston in ’56:

How the World Changed in 6 Months

Houston is one of the most-favored cities in the Elvis Universe. The King of Rock ’n’ roll played that Texas town 16 times during his career. It started in November and December of 1954, when Elvis and The Blue Moon Boys twice made the 575-mile drive from Memphis to appear at the city’s Paladium Club and Cook’s Hoedown Club. The following year, Houston hosted Presley seven more times at the Hoedown Club, Eagles Hall, and Magnolia Gardens. In those early years of his career, Elvis was still recording on Sun Records, refining his style, and spreading his name across the South.

Elvis’ most revealing appearances in Houston came later in his breakout year of 1956. In April and October of that year, Houston teenagers saw just how explosive that breakout became. When Presley’s troupe rolled into town for two shows on April 21, 1956, he had become already a national figure in the music business. He had appeared with the Dorsey Brothers and Milton Berle on their national TV shows, and his first RCA single, “Heartbreak Hotel” was only two weeks away from reaching the #1 spot onBillboard’s “Top 100” pop chart. However, by the time he came back to Houston in October, all hell had broken loose with the Elvis phenomenon. Looking back at those two shows reveals the enormous influence Presley had on pop culture during the six-month interim between them.

• Houston, Texas | Saturday, April 21, 1956 | Municipal Auditorium

“Singer Elvis Presley, the Western version of Johnny Ray and the current bobby sox swooner, will come here for two shows Saturday night at the City Auditorium. It will be Presley’s first Houston visit since his rise to fame in the entertainment world.” Thus columnist Charlie Evans announced Elvis’ return to Houston in the Houston Chronicle on April 16, 1956.

Having outgrown the Paladium and Hoedown Clubs, Presley was booked into the 4,000-seat Municipal Auditorium for two shows at 7:30 and 9:30 p.m. Ads in the Chronicle touted Elvis as the “Sensational RCA Victor Artist” and a “Coast to Coast Television Star.” Advance general admission tickets were priced at $1.50. Presley, who was headlining his own show now, brought along a cast of opening acts, including singers, dancers, and comedians.

A blurb in the Chronicle two days before the show acknowledged how far Elvis had come up in the entertainment industry since his last Houston appearance the previous summer. “Just 21, Elvis is called the greatest new personality of recorded music to be discovered in the past 10 years,” the article noted. “His combination of talent, good looks and great showmanship has young Miss America in a dither that surpasses even that stirred up by Frank Sinatra some years ago.”

There were no warning signs, however, in the press about the controversial nature of Presley’s stage show or its possible harmful effects on “Miss America.” In fact, John Greensmith, then a Chronicle staff photographer, recalls that the Houston press had very little interest in Elvis in April 1956.

“After explaining who I was and what I would like in the way of photos for the newspaper,” explained Greensmith, “Elvis assured me he could give me all the time I wanted since the show didn’t start for 30 minutes. He seemed surprised and maybe a little disappointed that I was the only member of the press on hand. Thinking back on it, I can’t help wonder why no other news people were there. Maybe Elvis had not reached the point where they flocked and followed him wherever he went.” (By the time Presley returned in October, the Houston press had reached that point.)

When Greensmith first saw Elvis that night, the singer was sitting in front of a mirror combing his hair. “I hesitate to say it,” admitted the photographer, “but I recall thinking how greasy his hair was and wondering if he used crankcase oil to slick it down.” After being introduced to Elvis, Greensmith “was at first taken by how quiet he seemed and what a soft voice he had when speaking compared to the booming vibes he had when he sang.” He also recalls that Elvis was “not a very friendly person” but was “polite” and “most cooperative.” “And he did have a rather untrained and genuine charm about him.”

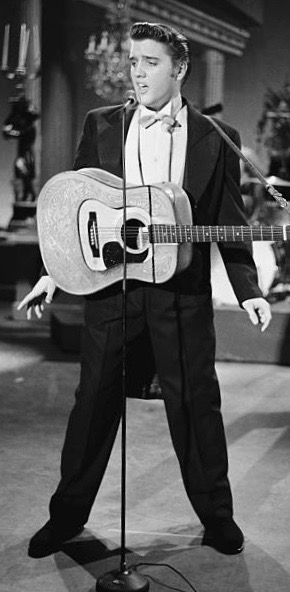

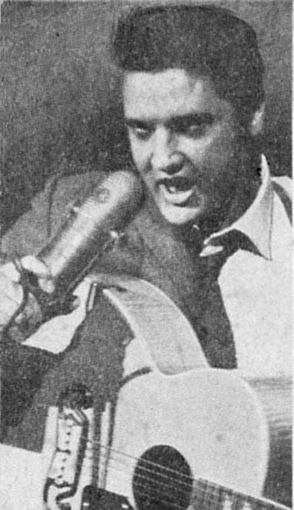

Bill Porterfield wrote the brief review of Elvis’ show that ran in the Chronicle the next day. It began: “A tall young giant from Tennessee strode out on the stage of Municipal Auditorium Saturday night—and pandemonium reigned. Four thousand teen-agers, filling every seat in the vast hall and overflowing into the aisles, squealed, moaned and screamed in ecstasy.”

According to Auditorium officials, the over 8,000 customers who paid to see the two shows that night comprised “one of the largest crowds to hit the auditorium in a long time.”

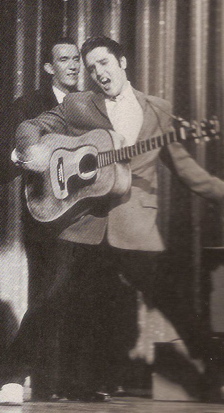

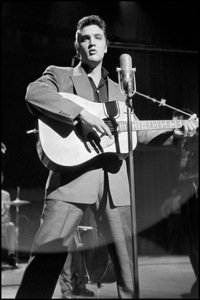

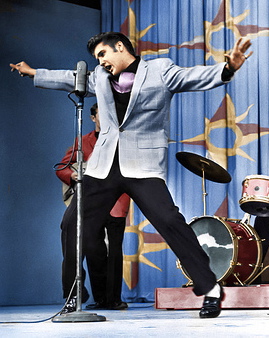

“Clad in a generously padded purple sport coat and black pants,” Porterfield observed, “Presley and his band knocked the roof off the hall with low down rock-n-roll blues and primitive rhythms.” While taking photos of the stage and crowd, Greensmith also noted the pandemonium going on around him. “Elvis came on stage and the crowd went wild. And that’s the way it went for the whole of his show. He sang softly, loudly, confidently and played his guitar gently or boldly as the song or mood dictated.”

According to Porterfield, a squad of police officers had no trouble holding back masses of young girls who pressed toward the stage to take photos. Greensmith agreed that the crowd never got out of hand. “There was no riot or close to what police and public worry warts felt might take place. All in all, it was a noisy but pretty tame afternoon.”

In fact, Elvis had not yet adopted the tactic of bolting from the stage and leaving the building following his final number. Instead, he ended his first show with a corny joke. “It’s been a wonderful show folks,” Porterfield heard him say. “Just remember this. Don’t go milkin’ the cow on a rainy day. If there’s lightning, you may be left holding the bag.”

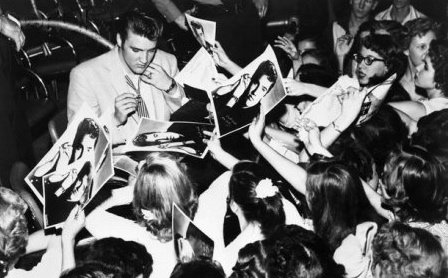

Greensmith noted as follows how easy it was for Elvis at that time to interact with his young fans:

“When the concert was over, Elvis came to the front of the stage and sat down at the edge to sign autographs on glossy black and white portraits of himself that were held up to him by probably about 100 admiring young women. No one tried to tear off a piece of his clothing or plant a kiss on him. It was all very civilized. But this was early 1956 and Elvis had not hit the peak of his fame that was to follow.”

When Elvis returned to Houston six months later, the environment would be far less “civilized.”

• Houston, Texas | Saturday, October 13, 1956 | Sam Houston Coliseum

By that fall Elvis Presley had become the biggest and most controversial entertainer in the country. “Heartbreak Hotel” had spent seven weeks at #1 that summer, and now his double-sided single of “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Hound Dog” was riding the top of the charts. A new single, “Love Me Tender,” had just been released. Presley had made controversial national appearances with Milton Berle in June, Steve Allen in July, and Ed Sullivan in September.

And so this time around concerns about Presley’s appearance were aired in the Houston press, which had been so silent when Elvis was in town six months earlier. The Chronicle published a letter from a frustrated mother on October 8. “I can’t keep still any longer,” the distressed writer declared. “It’s the raving teen-agers themselves, who will sound the death-knell for Elvis. They, with their antics, make people sick, so the people lash out at Elvis.”

And three days before Presley was due to appear in Houston, the Chronicle printed a photo of three University of Houston students displaying a “We hate Elvis Presley” petition being passed around campus. The petition’s promoters wanted Elvis’s records banned from the student snack bar jukebox. They planned a mock execution of Presley, with the singer being burned in effigy the night before his Houston appearance.

The city’s Auditorium could no longer contain Presley’s fans, and so this time he was booked into the 9,000-seat Sam Houston Coliseum for two shows at 4 and 9 p.m. Advance tickets were still priced at $1.50, with seats $2 at the door.

From the beginning, it was clear that the “civilized” atmosphere present during Presley’s April show would not be recreated. Since there were no reserve seats, ticket holders began lining up at noon for the 4 o’clock show. According to an article in theHouston Post, “14 or 15 girls were overcome while waiting for the doors to open outside the Coliseum … those near the doors underwent considerable mauling as the crowd grew.”

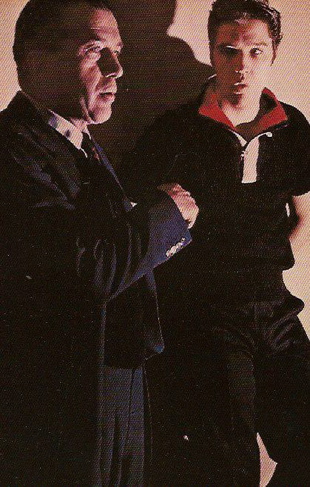

Elvis arrived at the Coliseum with a police escort and was hustled into a downstairs dressing room. Awaiting him there was a throng of people, not just a sole photographer, as had been the case six months earlier. First, a group of about 50 girls, fan club officers and the like, had been waiting there for over two hours. Elvis signed autographs, posed for photos, and kissed them all. After the girls were escorted upstairs, the doors were opened to the Houston press, most of which had something better to do when Elvis was in town the previous April.

Presley said he might tour Europe after appearing twice more on The Ed Sullivan Show and making another movie. He brushed off questions about the Hollywood starlets he had been dating and dismissed the supposed hysterical effects his stage gyrations have on youngsters. “If you get a bunch of teen-agers together,” he explained, “they’re gonna have a ball regardless.”

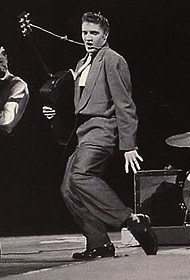

While perhaps completely “uncivilized,” an impatient crowd of over 8,000 awaited Elvis on the Coliseum floor. An announcer asked the crowd to sit down. Seeking help from the few parents there, he said, “Just remember, it might be your child that gets trampled.”

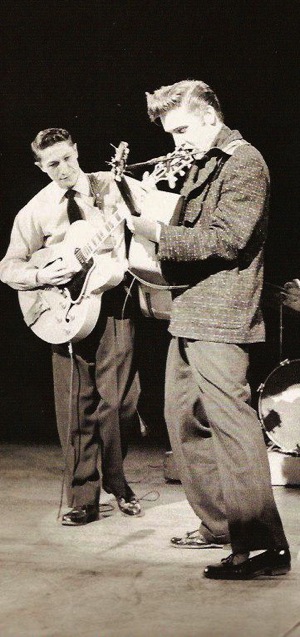

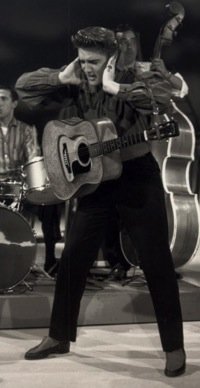

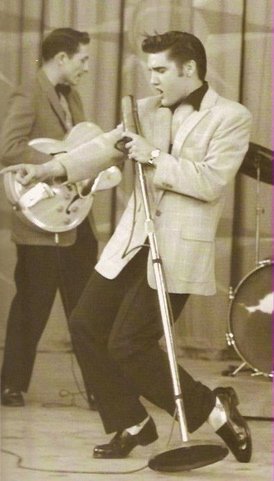

In a disparaging review in the Chronicle the next day, Dick De Pugh described Presley’s entrance: “Swept into the Coliseum by a police guard, the greasy, side-burned hillbilly took to the stage … Screams and lamentations kept up without relief for four minutes and 50 seconds. He entered the arena like a wild calf and began his bellowing to the tune of his million-seller, ‘Heartbreak Hotel.’ All that was heard of this number was the title. Screams from the crowd drowned out any other sound Presley could produce.”

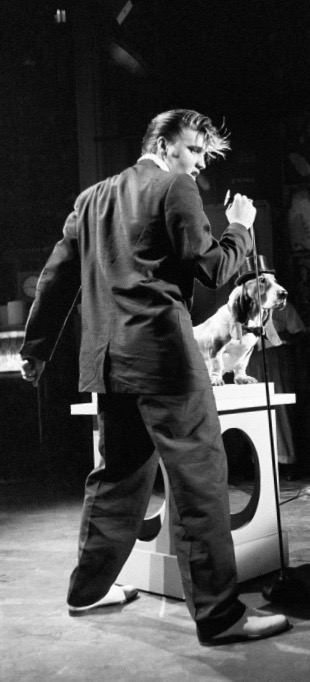

Unlike many journalists in those days, De Pugh at least knew the correct titles of some Presley songs. “Elvis rolled and wiggled through ‘Blue Suede Shoes,’” he reported, “added his hippy ‘oomph’ to an agonizing rendition of ‘Love Me,’ and pulsated vigorously as he groaned his ‘Long Tall Sally’ … He rocked on his toes, pointed to kids in the audience and sang to them, and made a quick exit on a little number called ‘Hound Dog.’”

De Pugh noted that 50 police officers, emergency corpsmen, and firemen manned the aisles to keep patrons from rushing the stage. The frenzied girls held back, but toward the end of the evening show, “a hysterical teen-ager with a flowing pony-tail broke through the police line surrounding the stage and rushed her idol,” De Pugh reported. “Police carried her back to her seat, but she had broken the ice. Teen-age girls en masse clamored for Presley, and rushed the stage until the singer was whisked off in a waiting police car.”

The days of Elvis sitting on the edge of the stage and signing photographs had ended for good. The Chronicle review ended with the pertinent statistics: “No one fainted. No one was injured.” Still, the size of the crowd, over 8,000 at each show, was twice as at Elvis’ Houston shows six months earlier.

The screaming, frenzy, and pandemonium seemed to increase fourfold. And while Colonel Parker pronounced the Houston crowd the “best controlled” on Presley’s current Texas tour, a fear of riotous violence at Presley shows had taken root in the minds of local officials in Houston and elsewhere. For the remainder of 1956 and all of the following year, that fear would cause civic officials and religious leaders to dread the announcement that Elvis Presley was coming to their town. — Alan Hanson | © August 2012

"Looking back at those two shows reveals the enormous influence Presley had on pop culture during the six-month interim between them."