Elvis History Blog

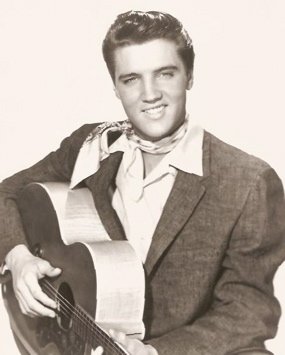

Elvis Presley’s Legacy

“Can You Even Imagine a World Without Elvis?”

I’ve stolen the above headline from Gillian G. Gaar’s article posted on Goldmine magazine’s web site on August 30, 2010. For some time now, I’ve been a fan of Ms. Gaar’s essays on Elvis. Her book, Return of the King, is one of the best Presley volumes to appear in years. However, while reading her “World Without Elvis” article, I found myself wanting to debate Gillian on a number of points. It seemed to me that she occasionally reached a bit too far in her efforts to stake out Presley’s legacy.

In her second paragraph, Gaar answers her title question. “Clearly,” she asserts, “Elvis’ legacy is one that has lived on and will continue to do so.” My main problem with her contention rests in the meaning of the word “legacy.” It can refer to a body of work that remains from an earlier generation, or it can refer to an inheritance handed down from a previous time. Gaar spends the rest of her article trying to defend the latter interpretation, that Elvis still influences music in the present day. On the other hand, to me it seems that it’s Elvis’ “memory” that has “lived on and will continue to do so,” and that his ability to influence music ended long ago.

Certainly, Elvis is remembered, and fondly so, by many people today. There’s plenty of evidence to prove it, and Gaar lists some of it. Milestones in Presley’s life are celebrated annually with updated releases of his music, most recently the mammoth Complete Masters 30-CD set. His movies continue to appear on DVD, and the 600,000 visitors a year at Graceland make Elvis’ former home the most visited private residence in the country. Elvis Presley Enterprises markets memorabilia and souvenirs, including Teddy Bears clothed in everything from jailhouse stripes to army fatigues to black leather to jump suits. But Gaar’s essay deals primarily with Elvis’ musical legacy, so let’s focus on that.

• Elvis turned the music world upside down

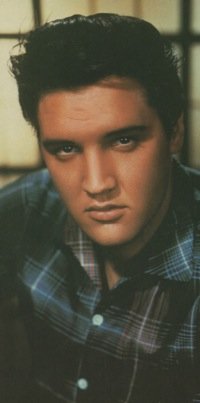

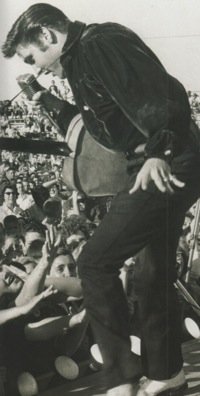

She contends that in the fifties, “ … no one turned the music world upside down quite like Elvis.” She allows that Sinatra attracted hordes of teenagers before Elvis and that other singers, such as Frankie Laine, had already started bringing “black musical influences into the white mainstream.” What Elvis did, as Gaar correctly identifies, was to popularize the newly termed rock ’n’ roll music. She notes, “ … if Elvis wasn’t the first to record a rock ’n’ roll record, he was the first to achieve great success with [the] genre.” Rock ’n’ roll radio stations sprang up in communities all around the country to play Elvis’ records, and that opened the door for other rock acts, both white and black, to get national exposure.

And while Elvis himself admitted that he didn’t invent rock ’n’ roll, there’s no doubt that he helped mix the sounds the characterized that new category of pop music. Elvis embraced everything from Arthur Crudup’s blues to Dean Martin’s crooning, Hank Williams’s yowling, and Johnny Ray’s emotional ballads.

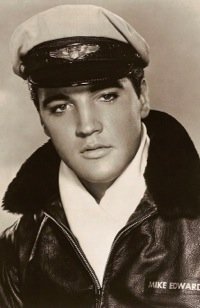

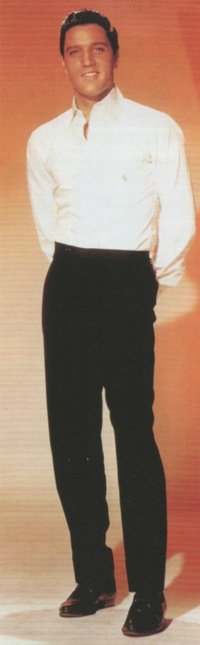

Add in Presley’s high energy delivery and sex appeal (no small contributions) and you have encapsulated the musical legacy that Elvis’ created in the fifties. The question is, “How much of that legacy continued to influence music in the future, and how much remained in the 1950s for us to marvel at?” It is in answering that question that I must differ with Ms. Gaar.

Gaar correctly points out that Elvis opened the door for and influenced such rock ’n’ roll artists as Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, and Ricky Nelson. Later singers, such as Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and Bono also acknowledged Presley impression on them. A little less convincingly, Gaar suggests that the $35,000 RCA paid for Elvis’ contract allowed Sam Phillips to build up Sun Records and boost the careers of Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, and Roy Orbison. (Something tells me this crew would have made it somehow anyway.)

• Would The Beatles even had existed without Elvis?

Then Gaar moves to Elvis’s influence on The Beatles, and John Lennon in particular. “ … it was Elvis who made them confirmed fans of rock ’n’ roll,” Gaar contends. As it was Presley around whom rock ’n’ roll coalesced in the fifties, she may be right about that. But if you look at The Beatles’ recorded music for Capitol in the mid-sixties, you find covers of Chuck Berry (“Rock ’n’ Roll Music,” “Roll Over Beethoven”) and Carl Perkins (“Honey Don’t,” “Matchbox”) but none of Elvis, suggesting that other early rockers had more direct influence on The Beatles than Presley.

It is at this point that Gaar starts to lose me as she suggests that a Presley ripple effect projected his musical influence far into the future. “Without Elvis as a catalyst, would The Beatles themselves have lacked the push to make music into a career?” she asks, “ … What then would have become of the British Invasion. If there hadn’t been The Beatles, would there have been The Rolling Stones? The Who?” As I eyewitness to the British Invasion in the sixties, I can testify that the event was not seen a vindication of Elvis’ musical influence. It was a body blow to Elvis at the time, as it was to dozens of other singers who emulated him.

In any event, The Beatles moved pop music off in a totally different direction from Elvis’ brand of fifties rock ’n’ roll. They were able to do it because Lennon and McCartney were extraordinary songwriters. His inability to write his own songs left Elvis vulnerable throughout his musical career. He was always at the mercy of the material that was offered to him. When the quality of songs written for him deteriorated, so did his influence in the music business.

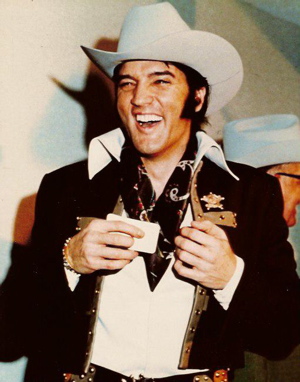

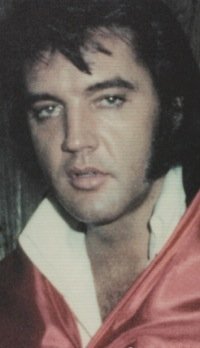

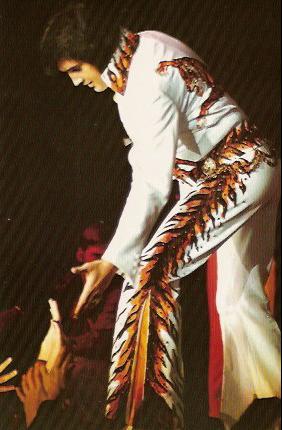

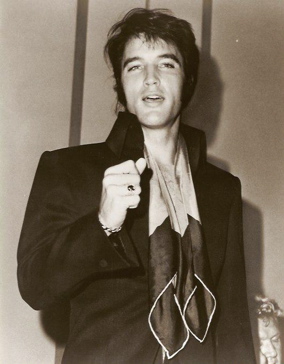

Gaar goes on to present her case for Elvis’ influence on the music business in the 1970s. She points out that during his comeback TV special in 1968, he pioneered the small, “unplugged” show format that later became popular. (The fact is that the “sit-down” segment of the NBC show was the producer’s idea, not Elvis’.) She refers to Elvis’s impact on Las Vegas, the rise in popularity of Elvis impersonators, and the Elvis-related catchphrases that invaded the cultural lexicon. All of which strike me as indications that Elvis’ past legacy is remembered these days, but not that it is continues to influence contemporary musical trends.

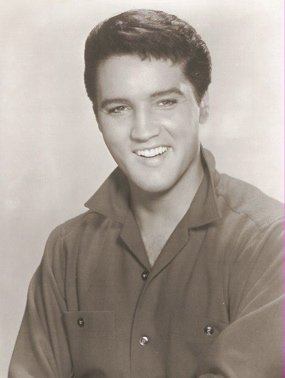

• Elvis’ musical legacy ended in 1958

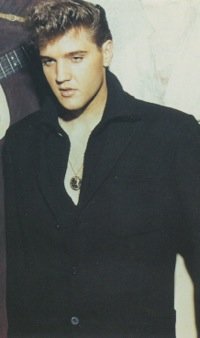

All right, let’s cut to the chase. Peter Guralnick got it right when he ended the first volume of his Presley biography with Elvis sailing off to Germany in 1958. When that troop ship disappeared over the eastern horizon, so did Elvis Presley’s ability to influence pop music. When he returned from the army two years later, he had changed, physically and musically. “He was much tamer live,” noted Elvis insider Jerry Schilling in a recent interview. “He was evolving. Some people wanted him to stay the same … But there comes to a point where you have to move to the next level or you don’t survive.” In the early sixties, Elvis slipped into pop’s mainstream with songs like “It’s Now or Never,” “Are You Lonesome Tonight,” and “Surrender.” Of Elvis’ 1961 live show in Memphis, Schilling says, “It was a classier show. But I have to say that my favorite times of Elvis onstage were in the Fifties with all of his rawness and unpredictability.”

Today there are many loyal Elvis fans who recognize that Presley’s musical and cultural legacy is limited to his work in the 1954-1958 period. Recently I was contacted by an Elvis fan looking for “unusual and cool” images of Elvis that he could use on a wall mural in a new house he was building. He was only interested, though, in images of a younger Elvis. “I don’t particularly care for Elvis of the 1970s,” he explained. “He became more an object of curiosity, of enduring charisma, and past mega-fame, than of musical importance.”

“Elvis Presley means many things to many people,” Gillian Gaar concluded at the end of her Billboard article. “And certainly anyone interested in popular culture from the mid-‘50s on has been touched by his influence, whether they’re fans of Elvis or not.”

If that’s the case, many “20-somethings” these days are totally unaware of how Elvis has “touched” them. In 2007 Dan Webster of The Spokesman-Review asked some members of the iPod generation to assess the relevancy of Elvis Presley in their lives. “I’ve never had a conversation about Elvis with anyone my age,” answered Chris Kornelis, 25, Web editor of the Seattle Weekly. “I don’t think I’ve ever owned an Elvis record. I don’t have Elvis on my iPod.”

• Even Junkie XL couldn’t connect with Elvis

Even Junkie XL, the Dutch musician whose remix of Elvis’ “A Little Less Conversation” was a modest hit a few years ago, finds it difficult to make a personal musical connection with Presley. “I’m sure that the people I listen to really have more of an appreciation for him, or definitely been influenced by him,” he allows, while seeing only one way in which Elvis has been even remotely important to him. “I make a modified Elvis sandwich, as I call it,” he explained. “Except I just do peanut butter.”

So I have to respectfully disagree with Gillian Gaar about the ongoing impact of Elvis Presley’s musical legacy. Undeniably, he had immense influence on the course of pop music in the 1954-1958 period. He affected (some would say “infected”) American popular culture at multiple levels and drew to himself a multitude of followers, including me, who will remain loyal to him throughout their lives. They will keep alive the legacy of Elvis Presley, that being the memory of what he meant to them in their youth. But the notion that he still has the power to influence the music of this or any subsequent generation is an illusion.

Yes, I can imagine a world without Elvis. What I can’t imagine, though, is my life without Elvis. — Alan Hanson | © September 2010)

Reader Comment: I too read the Gillian Gaar article, and I agree with your perspective on Elvis' lack of continued influence on popular music beyond the 50s. In addition, I disagree with her contention that Elvis opened the door for Little Richard (and other 50s rockers). The fact is that Little Richard's first hit, Tutti-Frutti, reached the Billboard charts six weeks before "Heartbreak Hotel." Elvis arguably brought more exposure and sales to Little Richard's music, but Little Richard opened his own door. Concerning Elvis' influence on the British Invasion, I love the quote on Scotty Moore's website by Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones: "Everybody else wanted to be Elvis. I wanted to be Scotty." — Phil Arnold

Go to Elvis Music

Go to Home Page

"The question is, 'How much of Elvis' legacy will continue to influence music in the future, and how much will remain in the 1950s for us to marvel at?'"