Elvis History Blog

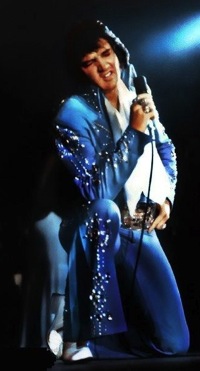

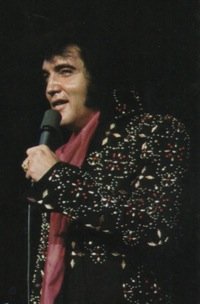

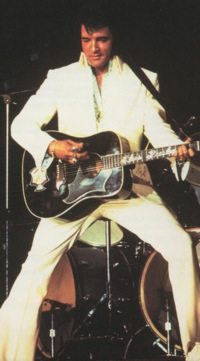

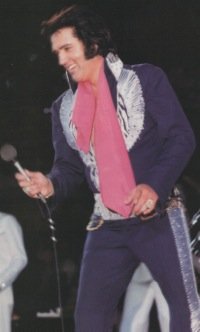

A Different Elvis Went Back On Tour in September 1970

On November 11, 1957, Elvis Presley left the stage at Schofield Barracks near Honolulu to conclude a four-city tour of California and Hawaii. At the time, he had no idea that it would be nearly 13 years before he would take his show on the road again. Colonel Parker had already sketched out a tour for 1958 after Elvis completed filming King Creole, but a dreaded draft notice arrived on Christmas Eve to scuttle Parker’s plans.

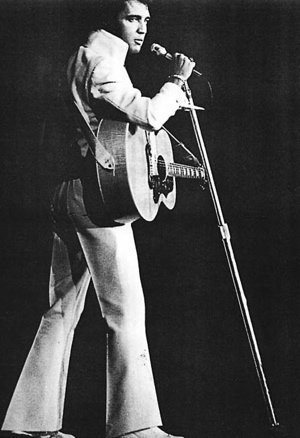

After Elvis’ army discharge two years later, he played a couple of one-day concerts in Memphis and Honolulu in 1961 before spending the rest of the sixties concentrating on a Hollywood career. Finally, in the summer of 1969, Elvis went back to the stage, but at first only in the safe confines of a Las Vegas showroom. Following 114 shows during two stints at the International Hotel, Parker tested tour possibilities by booking Elvis for six performances in the Houston Astrodome in early 1970. The crowds that came out to see Elvis there confirmed Parker’s belief that a return to touring the country would be profitable.

An article in Billboard on August 22, 1970, announced the initial Presley tour. It was to be an odd combination of cities, beginning with Phoenix on September 9, followed without a break by shows in St. Louis, Detroit, Miami, Tampa, and closing in Mobile on September 14. (Colonel Parker indicated that the widely spaced stops allowed him to address commitments he had made for Presley appearances back in 1958.) Parker would handle the arrangements himself for the Phoenix and Tampa shows, but he hired Jerry Weintraub and Tom Hulett, experienced promoters of big name rock shows in the sixties, to take care of business in the other four cities.

Parker knew the tour was going to make money. The coliseums and arenas in all six cities sold out quickly. His concern involved organizing a rock tour, the complexity of which had increased ten-fold since he had last done it in the fifties. Parker decided to retain some of the strategies from Elvis’ early tours and change others. To insure sellouts and make Presley accessible to the masses, ticket price were kept relatively low at $10, $7.50, and $5. The show content followed the pattern of the fifties shows—over an hour of inconsequential opening acts, an intermission, and 50 minutes of Elvis.

• No time for interviews, said the Colonel

Gone, however, was the standard Elvis pre-concert press conference of 1956-57. “We just don’t have time for that sort of thing,” Parker announced a week before the tour opened. Press coverage of Presley shows, vigorously promoted in the fifties, was effectively discouraged on the new tour. Newspaper writers had to buy tickets like everyone else for the privilege of reviewing Elvis. In Phoenix, photographers, who also had to buy tickets, were kept away from Elvis before the show, and, according to Ken Burton of the Tucson Daily Citizen, when they tried to get some shots of Elvis on stage, “They were first asked for credentials, allowed to shoot The King and were then summarily yanked by their collars away from the stage.”

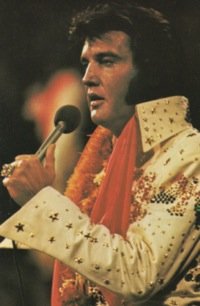

The number of background singers and musicians supporting Presley was greatly expanded from the early days. In 1957 just seven others shared the stage with Elvis. They were guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black, drummer D.J. Fontana, and the four Jordanaires. Elvis had put together a new and expanded stage band for his Las Vegas shows, and that set, along with vocal backing groups The Imperials and the Sweet Inspirations were invited to be part of the tour entourage.

Parker had a problem, though, when The Imperials declined, citing previous commitments. The Colonel then asked Hugh Jarrett to put together a male quartet in time for the Phoenix show. Jarrett then became the only one of Elvis’ fifties stagemates to join him on tour in the seventies. (The Jordanaires had fired Jarrett as their bass singer in 1958 and replaced him with Ray Walker. Elvis had inquired about the Jordanaires backing him in Las Vegas in 1969, but the group, which had steady sessions work in Nashville, declined.)

In Las Vegas, Elvis also worked with the Joe Guercio orchestra, but in a cost-cutting move for the first tour, Parker decided to take only Guercio and a single trumpet player, filling in the 15-piece orchestra with local musicians in each city. Guercio later recalled the stress of that first tour: “It was pretty funky compared to what came later. Most of us were traveling in a Granny Goose airplane. We called it Greyhound Airlines. Oh, it was pretty together, but we didn’t know how much equipment we needed and we had different pickup musicians in every town. We were doing a show every day and when you’re rehearsing new horns and strings every day, you want to cut your wrists.”

• Bomb threat delayed start of Phoenix show

After completing his third engagement at the International Hotel, Elvis flew out of Las Vegas on September 8, 1970, to open his first tour since 1957 in Phoenix the next night. The first of several glitches in that opening show occurred that afternoon. In an essay originally published in Strictly Elvis magazine, Debbie Lynn Gobins, then 12 years old (soon to be 13), recalled what happened when she arrived at the Phoenix Veterans Memorial Coliseum two hours before show time.

“There were big lines of Elvis fans at each of the many entrances. We waited, and finally 7:30 came when the doors normally would open … but they did not. When 8:30 came I started to wonder if Elvis was O.K. I thought that I might not even get to see the King. But finally, the doors opened at 8:30. I later found out that someone had made a prank call stating that there was a bomb set to go off in the Coliseum at 8:30, when the show as to start.”

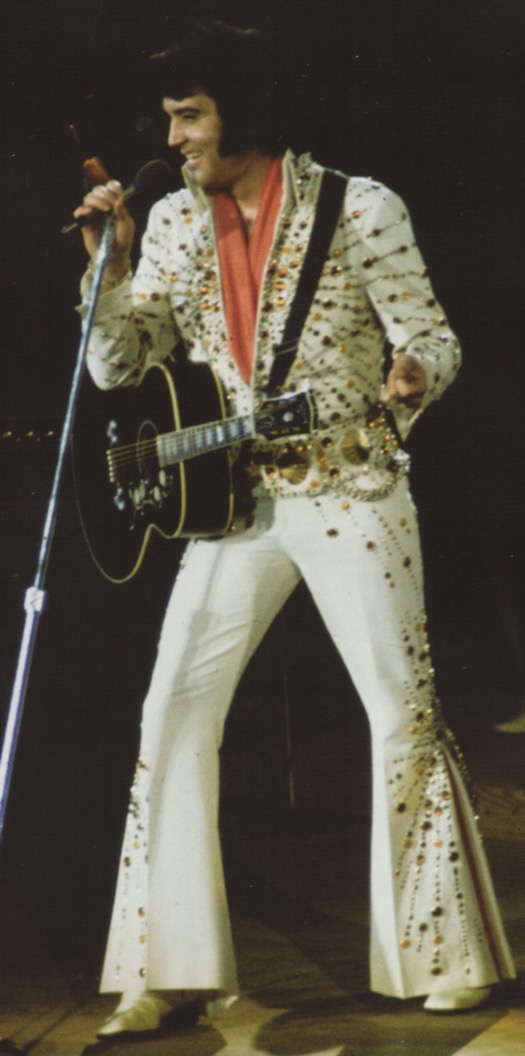

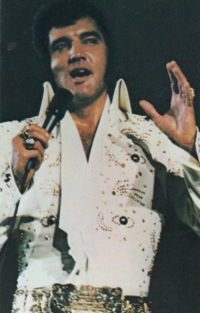

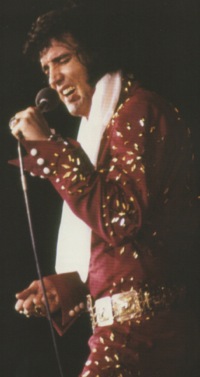

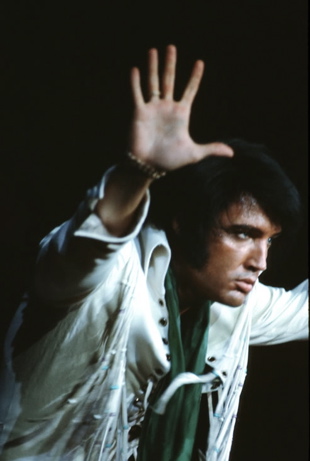

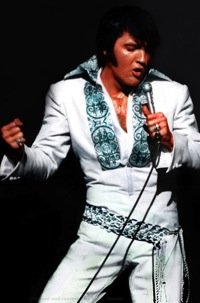

After being tortured by the opening acts for an hour, the crowd responded when Elvis finally appeared. “Elvis, looking as sexy as a 35-year-old can look, sauntered onto the stage,” Burton noted in his review the next morning. “Before you could say ‘Don’t Be Cruel,’ the squeals went up—largely from the part of the audience that must have been 3 or 4 years old when Elvis started the whole thing.”

In the fifties, teenagers made up 90 per cent of the crowd at Presley shows. In 1970 Phoenix, however, it was a mixed audience that filled the seats. In an article in The Arizona Republic, Jerry Eaton described the new Elvis demographic, the one that would come out to see him throughout the 1970s:

“Teenagers were there but the socio-economic composition of the crowd was different than in 1956. The establishment was on hand—blondes, brownettes, brunettes, Presley’s contemporaries and those not many years his junior. Presley’s male contemporaries were there, too—ex-motorcycle drivers who have shed black, leather jackets for business suits and other garb of the real world of work, veterans of Seoul and Pork Chop Hill, professional men, mid-managers, others. They were all there—the beautiful people, the well-mannered, well-dressed teenagers, a few senior citizens, some fading flower children, some young bearded hippies.”

• House sound system inadequate in Phoenix

Soon after Elvis arrived on stage, Colonel Parker learned a lesson about modern rock concerts. In the cozy environment of a Las Vegas showroom, the house sound system worked well enough, but it was pitifully inadequate in the raucous atmosphere of an arena concert. On stage in Phoenix the audience couldn’t hear Elvis and the singers couldn’t hear each other. At times the background singers overpowered Elvis, and on at least once song, he had to stop and start over. It was the last time Elvis performed on tour using a public address system. The next night in St. Louis, Weintraub and Hulett had a state-of-the-art sound system on stage, and, according to Hulett, “probably for the first time in his life, [Elvis] heard himself.”

While Parker was struggling with logistics, Elvis had to make decisions about his music. It was easy for him in the fifties—just sing all your hits and throw in a few other contemporary rock ’n’ roll numbers. In 1970 he understood that’s what his new audience wanted to hear most, but he couldn’t just live in the past. He had a need to show he could handle trendy pop music and compete with the likes of Tom Jones.

When he first went on tour in 1970, Elvis decided to employ the same musical repertoire he had compiled for his Las Vegas audience. There was no guarantee that it would work on the road, since tour crowds were much more diverse than the Vegas showroom regulars. Still, Elvis decided to stay with a mix of old and new.

Debbie Gobins wrote down Elvis’s Phoenix playlist, which presumably was used again the following five nights. It included, “That’s All Right,” “I Got a Woman,” “Love Me Tender,” “I’ve Lost You,” “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” “Polk Salad Annie,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “The Wonder of You,” “In the Ghetto,” “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Kentucky Rain,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Hound Dog,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Suspicious Minds,” and “Can’t Help Falling in Love.”

In the Tucson Citizen, Burton categorized Presley’s selections as “something borrowed (‘That Lovin’ Feelin’’ from the Righteous Brothers), something new (‘Kentucky Rain’), something old (‘Hound Dog’) and something blue (‘In the Ghetto’). Some reviewers along the tour stops noted that, although the crowd responded more enthusiastically to the old songs, they were the ones Elvis seemed least interested in singing.

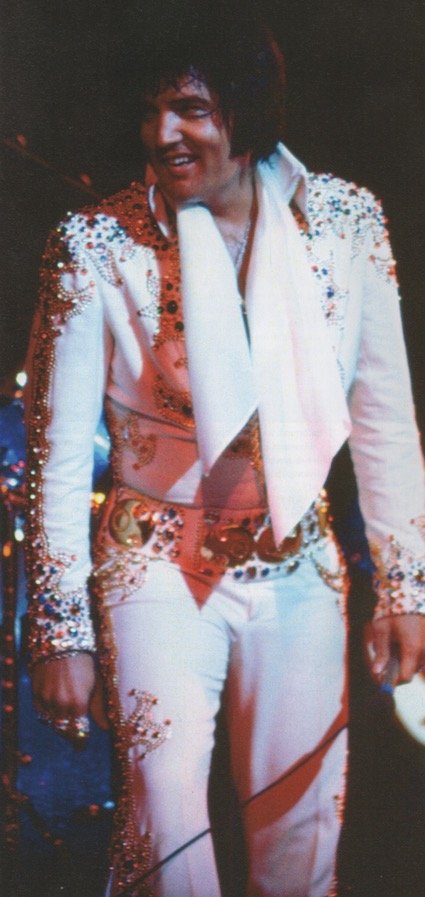

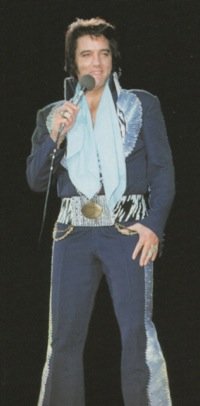

• Elvis scarf tradition began in Phoenix

In Phoenix, Elvis started a stage tradition that continued during all his tours in the seventies. He pulled the green scarf from his neck and threw it to a fan in the front row. Of the lucky recipient, Burton noted, “She screamed well enough to be a member of the Class of 1955, but she wasn’t old enough.” The act played so well that it wasn’t long before Elvis was doling out multiple scarves at every concert.

When that initial tour ended in Mobile at September 14, 1970, a euphoric Elvis flew back home to Memphis. He loved the freedom of the road and doing what he always called his favorite part of the entertainment business—performing before a live audience. That first tour would be followed by 25 more over the next six years. The last one ended in Indianapolis on June 26, 1977. And, of course, Elvis planned to start still another tour on the very day that he died.

Hundreds of thousands of his fans had an opportunity to see Elvis Presley during those tours that began in the fall of 1970. I was fortunate to see him at his best (Seattle in 1970) and at his worst (Spokane in 1976), and I’ll be grateful for both opportunities. — Alan Hanson | © April 2013

"Parker knew the tour was going to make money … His concern involved organizing a rock tour, the complexity of which had increased ten-fold since he had last done it in the fifties."