Elvis History Blog

Hysteria at Elvis’ ’56 Tulsa Show

Like Tossing Christians to Lions

“The feature article on Elvis Presley’s show by David Wood was one of the most admirable pieces of local feature writing I have come across. His irony was fine and incisive, without being truly offensive to anyone.”

Thus Tulsa, Oklahoma, citizen Phil Bolian noted in a letter-to-the-editor in The Tulsa Worldon April 29, 1956. David Wood’s review had appeared in the World 10 days earlier, the day after Presley played the city.

Although Wood’s article was tucked way back on page 33 of the paper’s April 19 issue, it truly was an impressive effort. Running nearly 4,000 words, to that point it was easily the longest and most descriptive day-after newspaper review in the young singer’s career. Although Elvis was already a hot commodity by mid-April 1956, the full explosion of his popularity was yet to come. When he rolled into Tulsa that spring, the mid-stop on a seven-city swing through Texas and Oklahoma, “Heartbreak Hotel” hadn’t yet reached #1 on the record charts, and his controversial appearance on The Milton Berle Show—the event that really broke the dam wide open—was still six weeks away. Yet, Wood seemed to know he had seen an event of historic proportions in Tulsa on the evening of April 18.

Wood led off his article as follows: “The bobby soxers’ dream man, a frenetic 21-year-old singer named Elvis Presley, came to Tulsa Wednesday night and the expected bedlam ensued at the fairgrounds pavilion where thousands of teen-agers screamed and panted until they were limp.”

Newspaper ads the previous week announced Presley’s coming appearance in Tulsa. Tickets went on sale at Walgreens at 4th & Main for two shows—at 7 and 9 p.m.—on the following Wednesday. The Fairgrounds Pavilion accommodated 8,000, and half of those seats could be had for $1. Reserved seats were priced at an unspecified “extra” amount.

• “The air was electric” at the turnstiles

The 7 p.m. show, the one Wood attended, was a sellout. “There wasn’t a junior high school in Tulsa that didn’t have a sizable representation,” Wood observed. “By 6:30 p.m. the air was electric. An apparently endless line of teen-agers, most of them girls, was jostling and pushing toward the turnstiles. Several carloads of youngsters in wheelchairs or on crutches were taken in and given choice seats near the stage. A dozen youths parked motorcycles, adjusted black leather jackets and elbowed their way through the crowd.”

Vendors hawking souvenir programs and glossy photos of Elvis clogged things up just inside the entrances. Three girls just ahead of Wood paid a dollar for a picture, and then “blocked the way to the hot dog stand while they made atavistic sounds over it,” noted the writer. “Only the phrase ‘How dree-ee-am-eey’ could be distinguished.”

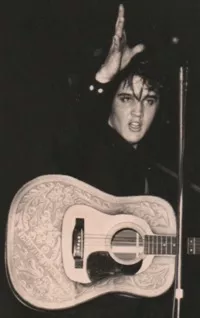

The crowd initially treated the opening acts with respect. “If we get this kind of an ovation, I shudder to think what you’ll give Elvis Presley,” Leon McAuliffe said after his western swing band finished up. But when another band came on instead of their idol, the crowd started to get restless. “There was the rhythmical clapping that is heard when rallies loom in ballparks,” Wood reported, “and a cadence of ‘We Want Elvis’ went up that made the 1940 Republican convention’s ‘We Want Wilkie’ sound like a whisper.” The assembled multitude quieted a bit when Oklahoma girl Wanda Jackson sang “You Cain’t Have My Love” with what Wood called “a western accent the authenticity of which can’t be questioned.”

Amid much wringing of hands and biting of fingernails, the young girls grew restless. The “We Want Elvis” chant rose again, and “small missiles began to hit the stage.” A platoon of nine police officers assigned to guard the platform, realizing the inadequacy of their number, wrapped some wire and rope around the stage as a second line of defense. Finally, master of ceremonies McAuliffe brought on Elvis just before 8 p.m.

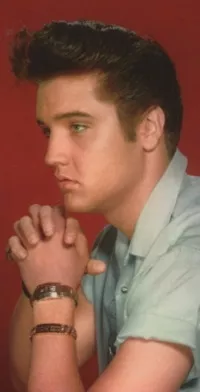

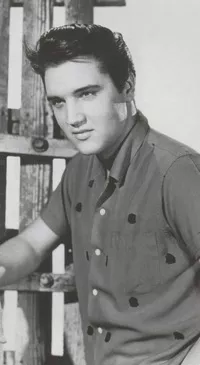

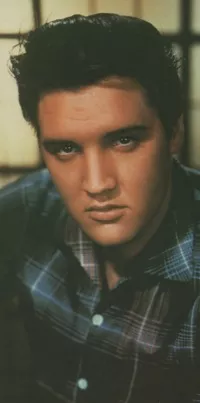

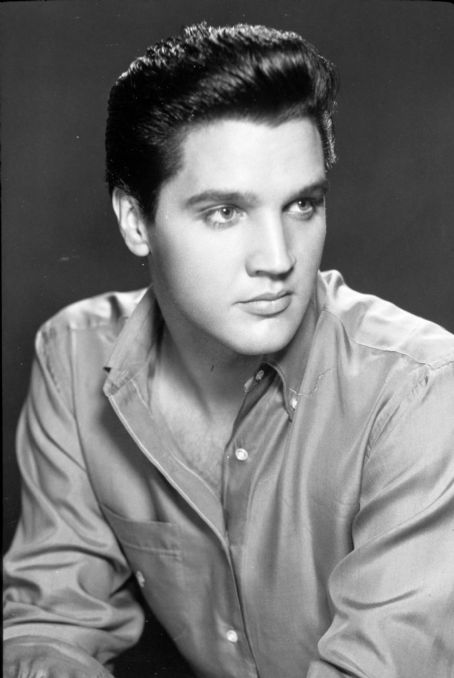

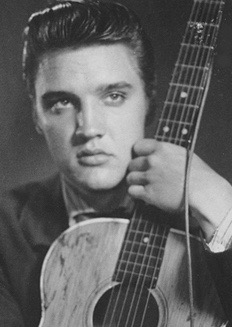

Wood watched “a slight young man with long, carefully combed hair, sideburns, and a face more beautiful than handsome” take the stage. “He hugged the microphone and complained rapidly and breathlessly that he was ‘sooh lone-a-ly.’ Many of the girls wept. Others just lifted up their eyes to the ceiling and screamed. Girls with his picture looked at it, at the singer on the stage, then at the picture again. They kissed the picture.”

• Writer couldn’t help but watch Elvis

Belonging to an older generation, Wood nevertheless viewed the pandemonium around him with an open mind. “After seeing the hysteria he could produce, it was impossible not to watch and listen to the young man in an attempt to discover just what it was about him that reduced these girls to a state that would have been pitiable if one hadn’t known they were enjoying themselves.

“He danced with his hips during each number, doing a form of dance called ‘Bop’ and shaking himself as though there was an entire hive of bees inside his clothes. At each shake of the hip, a great collective shriek approved it. The girls screamed when he ran his hands up and down his hips.”

Both the entertainer and his audience surprised Wood with their boundless energy. “It would have seemed that exhaustion would have claimed the audience but when Elvis began to sing and shake his finale, ‘Stay Off My Blue Suede Shoes,’ the teen-agers proved they had only been warming up. The girls straining behind the wire fought like caged animals to get past it. The first row disappeared as the youngsters left their seats and crowded to the edge of the stage.”

Finally, though, it was over, and Presley disappeared behind a curtain and retreated to a dressing room beneath the stands to await the second show. Wood was allowed in for an interview, but police officers held back a crowd of desperate youngsters who filled a ramp leading up to the dressing room. “Some teen-agers managed to get themselves hoisted to the open high windows of the dressing room,” the reporter noted. “One girl leaned in and begged Presley to shake her hand. When he did, she screamed and disappeared from sight.”

• Elvis spoke out on “painful subject”

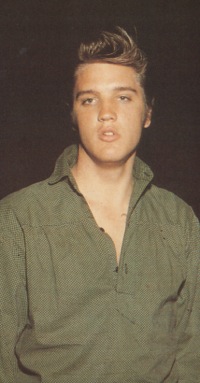

Sitting on a table and drinking pop from a concession stand cup, Elvis replied “quietly and unaffectedly” to Wood’s questions. “I just get nervous sometimes,” he admitted about the pandemonium swirling around him. “I get scared only when the audience starts hurting each other. That’s why I stopped giving autographs. The bigger kids run over the smaller ones and I’m always afraid they’d get hurt. That can be bad. After awhile the parents would stop letting their kids come to hear you.”

There was another subject bothering Presley at the time. When a member of his band asked him what he was drinking, Elvis responded, “Dope. You know I’m a pusher.” He spoke more on what Wood called that “painful subject.” “People ask me if I take something to make me do what I do out there. I don’t even drink alcohol. At first I tried to deny that I took anything but that didn’t seem to help. I switch to wisecracking, ‘Oh, just a mixture of my own—heroin, benzedrine, cocaine.’ I don’t guess anything can be done about it … it makes my mother mad. People have even phoned the house in Memphis to ask what I take.”

As Elvis relaxed and waited for the next show, Wood made his way to an exit. Outside a “line almost two blocks long inched toward the doors. At the 21st st. entrance cars were still turning into the grounds. It looked like another full house.” The only difference, according to Wood, was that this later crowd was older—“the senior high school contingent was in full force this time.”

Later, as he composed his review for the next day’s issue of the World, Wood summarized the event he had just experienced as follows:

“To the middle-aged spectators addicted to Brahms and Bach, the show left aesthetic tastes unsatisfied, but as a study in enthusiastic hysteria nothing could have been more rewarding since the Romans used to toss out Christians to the lions for entertainment.”

* * * * *

After his 1956 show in the city, Elvis paid tribute to Tulsa in his 1960 film G.I. Blues. (Actually, credit for recognizing Tulsa in the movie belongs to screenplay writers Edmund Beloin and Henry Garson.) Elvis’ character in his first post-army picture was named “Tulsa” McLean. Before entering the army, “Tulsa” was said to have worked in a gas station in his native Oklahoma, and after their discharge, “Tulsa” and his two soldier sidekicks planned to return to the state and open a hot nightspot on the Oklahoma Turnpike.

Elvis would return to Tulsa in real life, but not until 16 years later. On June 20, 1972, he brought his show back to the city’s Civic Assembly Center. He returned again in 1974 and 1976 for appearances at Oral Roberts University. — Alan Hanson |June 2011

Go to Elvis 1956

Go to Home Page

"Amid much wringing of hands and biting of fingernails, the young girls grew restless. The 'We Want Elvis' chant rose again, and small missiles began to hit the stage."