Elvis History Blog

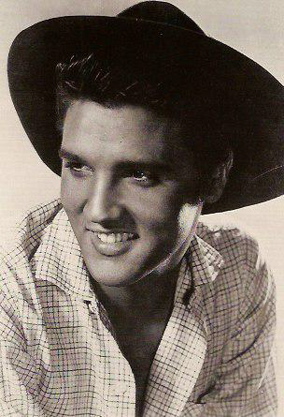

Hillbilly Elvis

How Journalists in the Fifties

Tried to Dumb-Down

Presley

“Show-wise people in the business can’t explain his amazing success. ‘Okay, so he’s handsome,’ they’ll admit. ‘And he comes on with a driving beat. But he sings hillbilly. And he slurs his words. And he bounces around on rubber legs.’”— Roger Beck, Los Angeles Mirror News, June 8, 1956

By mid-1956, most of the nation’s entertainment journalists couldn’t fathom the mystery of Elvis Presley’s appeal, much less explain it to their readers. When the Presley whirlwind passed through their towns, local reviewers did their best to express in print that which defied description. Often they went into metaphoric overdrive trying to depict his stage gyrations.

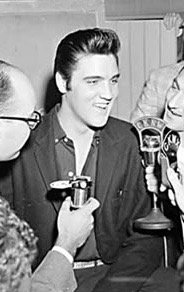

Just as big a part of the Elvis Presley paradox for journalists in 1956 was how a young man so obviously uneducated and untrained could rise so fast to the top of the entertainment business. As Presley’s popularity quickly grew in 1956, he dealt with the growing media interest in him by holding impromptu press conferences at his tour stops around the country. It was in that setting that the image of “Hillbilly Elvis” began to emerge.

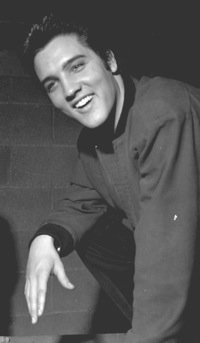

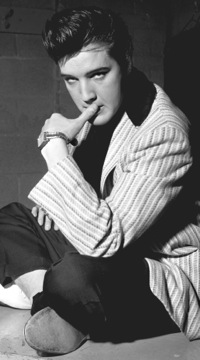

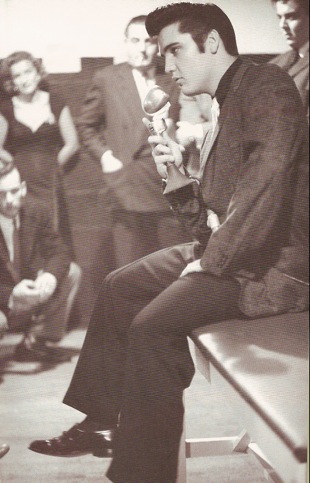

(Right: Los Angles press conference, October 28, 1957)

Presley helped foster the concept when answering the questions thrown at him. In Lincoln, Nebraska, on May 20, 1956, Elvis described his type of music as, “a little rock and roll and a little hillbilly.” In response to another question, he declared, “I don’t know too much more than how to write my name, and anyone says that I told them I was going to write a book is just plain crazy.” He referred again to his lack of “book-learning” in April 1957 when Angela Burke of the Toronto Daily Star asked him if he wrote home to his mother while on tour. “Honey, I haven’t written a letter since I left the sixth grade,” he declared.

Then there were the corny jokes he told on stage. In Las Vegas in May and again in Long Beach in June, Elvis mentioned a new song title to his audiences—“Get Out of the Barn, Grandma, You’re Too Old to be Horsing Around.” And prior to singing “Blue Suede Shoes” in Des Moines on May 24, 1956, Elvis told the crowd, “I dread to sing this next number because when I’m through I’ve just about had it. I’m just too pooped to pop after singing it.”

Some of the forgoing can be attributed to Presley’s self-deprecating sense of humor and his experience with the hillbilly style of showmanship that was popular in the South during the formative years of his career. It sounded truthful, though, when Elvis made the following statement at an August 1956 press gathering in Lakeland, Florida, about his appearance on the “Steve Allen Show”: “They told me to behave like a gentleman. I didn’t know what they was talking about.”

That latter sentence contains an example of a Presley tendency that the press often pounced on to exaggerate the singer’s hillbilly quality—his laid-back use of the English language. In addition to subject-verb agreement issues, illustrated in the Allen comment above, Elvis was prone to the use of double negatives, such as when a Lakeland reporter asked his feeling about the nickname “cat.” “I ain’t no damn cat,” Presley responded. His continued use of the term “ain’t” also added to his hillbilly quotient.

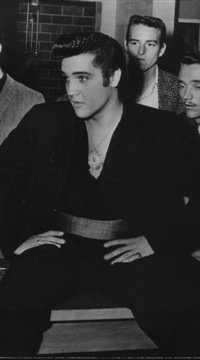

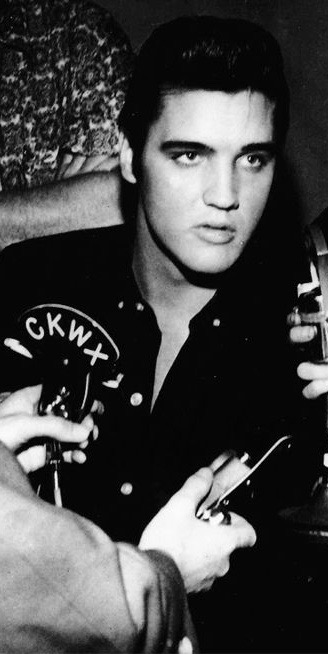

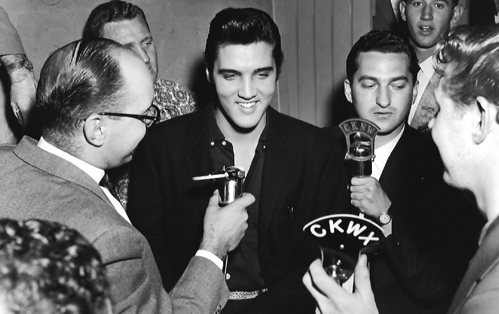

(Below: Vancouver B.C. press conference, August 31, 1957)

The most common Presley vocal tendency that many in the press loved to include in their reviews concerned his pronunciation. Raised in Mississippi and Tennessee, Elvis developed a Southern accent that was quite noticeable when he hit the big time at the age of 21 in 1956. Ralph Gleason of the San Francisco Chronicle called it a “thick southern drawl” and Shirley Phillips of the Arizona Daily Star labeled it a “heavy southern accent.”

When Elvis performed in Southern cities, reporters were used to the vernacular he used, and saw no reason to make a point of it in their reviews. Outside of the South, however, to many in the media at his press conferences, Presley’s drawl indicated a lack of culture and education. In their newspaper reviews, then, each reporter had to decide how to handle direct quotations attributed to Elvis. The majority of writers ignored Presley’s odd, to them, pronunciation, and used standard spelling when quoting him.

Many other journalists, though, chose to present Elvis’ comments phonetically in an effort to give the reader the feel of Presley’s Southern drawl or accent. For instance, consider how Gee Mitchell, writing in the Dayton Daily News on May 28, 1956, presented Elvis’ responses to a series of press conference questions the day before.

Q: “What do you have that sends girls?”

A: “Ah cain’t answer that. An’ anyhow, what difference it make? Long as they come see me. Ah love every one of ’em.”

Q: “Why do you move the way you do on stage?”

A: “Ah jus’ feel that way when Ah sing. Don’t know why some people think it ain’t decent.”

Q: “Do you think you’ll make it in the movies?”

A: “That’s what Ah wanta be, an actor. Like James Dean. Wanta be in a picture like Rebel Without a Cause. This’s too tough makin’ a livin’ this way. Movies you don’t work alla time. An’ make big money. That’s for me. Travelin’ alla time, Ah don’t get no sleep. Ah’m tard.”

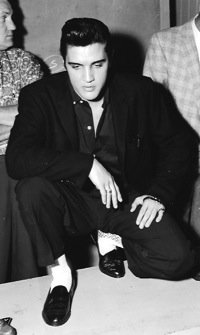

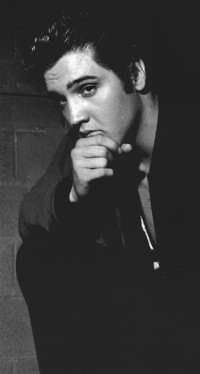

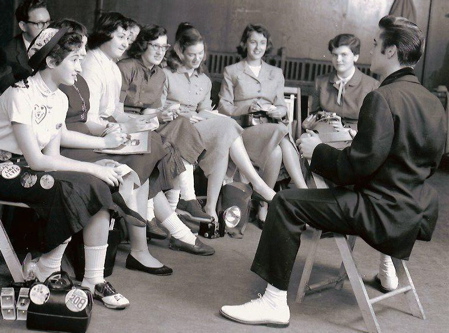

(Below: Philadelphia press conference, April 6, 1957)

Motives varied for fifties journalists who chose to phonetically report Presley’s comments. Some found his drawl quaint and pleasantly strange. For them reporting “Elvis-speak” literally was a way of humanizing the new rock ’n’ roll idol. More often, though, as in the case of Gee Mitchell above, reviewers who disapproved of Elvis’ stage act seized upon what they saw as his flawed speech to further diminish and dismiss him. They simply couldn’t believe that a gyrating country bumpkin like Presley could last for long in the proper pop music field that had developed in the post-war years.

For example, consider Betsy Milburn’s belittling writing in the June 11, 1956, issue of the Tucson Daily Citizen:

“How does he feel about being the current idol of the teenage crowd? ‘Well, it’s just fin, Ah guess,’ he drawled, removing a huge wad of gum from his mouth and tossing it nonchalantly over his shoulder. ‘Ah’ve got nine secretaries, a business manager, two promoters, a co-promoter and a valet—and those girls when they mob me, they don’t mean no harm. They don’ really try to tear mah clothes off—jes a button or two. Course, sometimes Ah get a little scratched. But they don mean to hurt me.’”

Here are a few more examples of “Elvis-speak” from fifties newspapers:

“Ah thunk they’re wunnerful. It makes muh want to live up to their opinion of muh.” — Ralph Gleason, San Francisco Chronicle, June 3, 1956.

“Ah just ain’t got the time. I date a few town belles heah and theah. But I just ain’t got time. Yo’ have to make it while yo’ can.” — Ray Parker, Los Angeles Mirror News, June 8, 1956.

“But ah’d sure like to invite some of the principals to one of the shows. They’d find there’ nothin’ wrong with the rock. Jumpin’, shakin’ and dancin’ ain’t indecent.” — James Purdue, Ottawa Journal, April 4, 1957.

“If you wanta see somebody make a idiot outta theirself, you should see me tryin’ to stand still.” — G.C., Spokane Spokesman-Review, August 31, 1957.

As his career progressed over the 1956-1957 period, Presley became more comfortable with the press conference format. While his Southern drawl didn’t disappear, it diminished in intensity. According to Angela Burke, writing in the Toronto Daily Star on April 3, 1957, “His accent was not too thick—just pleasantly tinged with a southern drawl.”

Burke was among an increasing number of journalists who began to praise Presley for how he handled their impromptu questions. “Elvis proved himself interesting, forthright and undeniably attractive,” Burke noted. “He was willing to talk on any subject and though his knowledge is strictly limited, he shows no lack of brains.” Marjorie Barnhart, writing in the Fort Wayne Sentinel on April 1, 1957, added, “He tried very hard to answer the questions fully and honestly. With dignity he fended off some personal probes and exhibited more intelligence that I had anticipated.”

The Ottawa Citizen’s Bob Blackburn was equally impressed: “Presley handles a press conference like a veteran statesman. He answers readily and intelligently, doesn’t try to weasel out of questions, doesn’t get huffy, and remains honest, even if it is to his disadvantage. And he tops it off with a sharp sense of humor and quick wit.”

While most journalists were warming up to Elvis in 1957, a few still insisted on portraying him as a Rube from Rubeville. Vancouver Province music critic Ida Halpern declared Presley “virtually inarticulate,” and Dick Williams included “Elvis-speak” in his viciously critical Mirror-News column that led to the Los Angeles police filming Presley’s concert at the Pan-Pacific Auditorium on October 29, 1957.

In the end, though, all of the efforts by 1950s journalists to portray Elvis Presley as a mumbling hillbilly proved to be counter-productive. His humble upbringing and unpretentious manner was part of his appeal to a generation of teenagers eager to escape the conformity of the post-war years. Don Oberdorfer of the Charlotte Observer was one of the few writers who early on understood Presley’s appeal: “Neither Presley’s mannerisms nor his singing nor his jokes are polished. Rather, they are actually awkward—and the crowd is with him the more for it.” — Alan Hanson | © October 2013

"Reviewers who disapproved of Elvis’ stage act seized upon what they saw as his flawed speech to further diminish and dismiss him. They simply couldn’t believe that a gyrating country bumpkin like Presley could last for long."