Elvis History Blog

Elvis and Other "Iconic Voices":

An Outrageous Celebrity Book

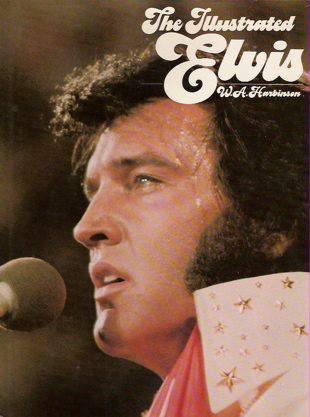

Does the name W.A. Harbinson ring a bell? It may if you were around when Elvis left the building for good back in 1977. Harbinson, whose Presley bio, The Illustrated Elvis, had just been published in the U.S. some months earlier, hit the jackpot when Elvis checked out that August. The presses at Grosset and Dunlop were fired up again to crank out thousands of copies of Harbinson’s book to satiate the grieving masses’s appetite for anything Elvis. The Illustrated Elvis was on display in every bookstore. I bought two copies myself—one hardbound and one soft.

Harbinson, who currently lives in West Cork, Ireland, has written other biographies—Charles Bronson, George C. Scott, Evita Peron. He takes another turn at Elvis in his latest book, Iconic Voices. In it Harbinson, writing in the first person, gives voice to five iconic personalities from the latter half of the past century. They are Elvis, Marlon Brando, John Lennon, Norman Mailer, and Andy Warhol.

The book opens with a 41-page pseudo “autobiography” by Elvis. In feeding often-outrageous statements through his Presley marionette, the author seems to be taking revenge for Elvis’ deceptions in life. You see, back in the seventies Harbinson, like the rest of us, had been duped into believing Presley was a paragon of virtue in his private life. The Illustrated Elvis was a rather pedestrian biography, portraying Presley as a “great natural artist, a monumental American figure,” to quote from the book’s final page. Elvis’s death, however, soon revealed an unknown, dark side of his character.

In Iconic Voices, Harbinson provides a much more candid overview of Elvis than he offered in his earlier book. In fact, most Presley fans are likely to find much objectionable in Harbinson’s treatment of their favorite son. But, then, they’re also likely to find some assertions about Elvis with which they agree. So Presley fans can expect to react with alternating passions when reading the treatment that Presley’s life gets in Iconic Vocies.

• This Elvis is stuck somewhere in the Afterlife

The premise is stated on the book’s back cover: “Iconic Voices is based on the conceit that all five are lost in the Afterlife, not quite knowing if they are dead or alive, but each remorselessly going over, in the first-person narratives, the highs and lows of their colorful lives … ”

It’s an interesting concept, at least as it applies to Elvis. Although he gave countless interviews and press conferences, Presley seldom made candid statements about his private life. Here Harbinson offers his version of how Elvis might have honestly assessed his life—the highs and lows, the regrets, the triumphs—had he ever chosen to do so.

There’s a feeling of uncertainty, however, in the author’s point of view. I found myself often struggling to decide whether Elvis’s statements in the narrative were founded in Harbinson’s personal opinions or in his beliefs about what Elvis really would have said. For example, in reference to June Juanico, an early girlfriend, Harbinson has Elvis say, “Man, she was stubborn! Had a mind of her own. Wouldn’t take shit from anyone—not even from me … So June, no matter how much I loved her, simply had to go.”

Now, is this Harbinson’s view of that relationship or is it his view of how Elvis saw it? In her book, June described how she saw Elvis briefly in New Orleans in 1957 to tell him she was engaged to someone else. If so, would Elvis later have falsely contended that he broke up with her? The answer is yes. He absolutely would have! Elvis would never have admitted that a girl rejected him. In this case, then, Harbinson put the right words in Elvis’ mouth.

• The Colonel called a “sly bastard” and a “sonofabitch”

There are other times in the narrative, however, when I had to disagree with Harbinson’s view of how Elvis saw things. One of them concerns how Elvis felt about Colonel Parker. Throughout the essay, Harbinson … I mean Elvis … disparages, condemns, and blames the Colonel for a multitude of sins. Some examples:

“Yeah, the Colonel sure knew how to play on my insecurities, my ongoing fear of a return to anonymity, even poverty, and I couldn’t resist his mesmeric, emotionally blackmailing ways.”

“Once Colonel Parker and those Hollywood producers realized that they could make fortunes off my back with cheap productions, crap scripts and lousy songs, they ignored my proven potential as a serious actor and dug my artistic grave with their trash.”

“The belief that my success was almost totally due to the Colonel—a belief carefully nurtured by him—was the one belief I could never shake off.”

“Then, of course, there was the Colonel, one of the world’s most brilliant schemers, manipulating this and manipulating that and starting to interfere with my music … and now addicted to gambling away fortunes in Las Vegas and selling me short to make up for his crippling losses.”

Harbinson’s personal hatred (there’s no other word to describe it) for Colonel Parker colors his Elvis narrative in these and other places. Certainly the quarrels between the entertainer and his manager increased toward the end of Elvis’ life, but Parker held the high ground in these disagreements. It was Elvis who was spiraling out of control, and the Colonel intervened in a futile effort to get his client back on track. I’d like to think that Elvis even then retained some respect for Parker, hardly a speck of which can be found in Harbinson’s narrative.

• Elvis’ runaway ego on display in Iconic Voices

Repeated references to Elvis’ exaggerated sense of his own importance is another recurring theme in Iconic Voices. “My crooked grin was beloved worldwide,” asserted Elvis, and he later asks, “Why did God anoint me with my great talent?” He later claims his “impassioned singing” of “If I Can Dream” in his 1968 Comeback Special “produced tears nationwide (then worldwide).”

This outpouring of self-importance from Elvis seems overdone in Harbinson’s essay. Surely Presley’s ego was over-inflated. How could it not be when devoted fans treated him like the greatest man to walk the earth since Jesus Christ? Surely, though, Elvis would never have forgotten his humble origins and retained at least a modicum of humility throughout his life. No hint of it here, though.

Harbinson’s make believe Elvis comments on many other aspects of his life and career. Here are some of them.

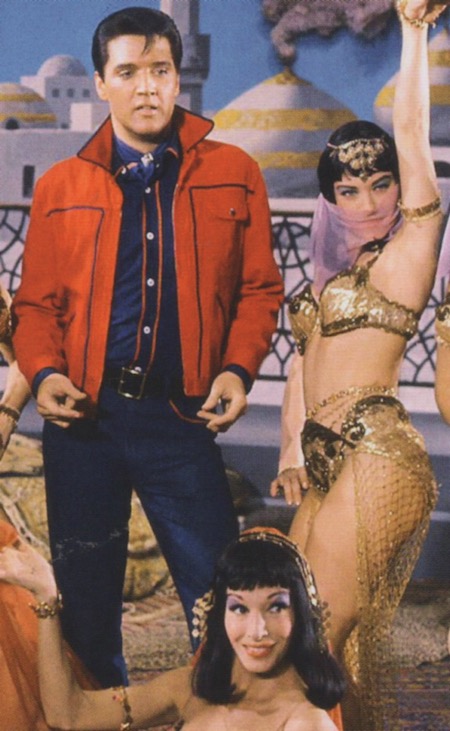

On his movies: “I was forced to spend the next eight or nine years making increasingly dumb movies in which I drove racing cars, flew airplanes, dived off cliffs, swung on trapezes, had a lot of fist fights, and sang songs written by the cheapest talents available to goofy kids and slobbering hound dogs and vacant-eyed bimbos in bikinis.”

On women: “I divided women into four different categories: (1) mothers; (2) wives; (3) daughters; (4) all the others. So though I was having all kinds of women, “the others,’ all over the place … when it came to serious relationships, meaning the possibility of marriage, I expected my chosen woman to be as I’d always imagined my mama to be: as pure as the driven snow.”

On drugs: “Drugs? I never took drugs! Medication, yeah, but that was all. For medicinal purposes. Codeine, Morphine, Methaqualone (that’s Quaalude, above toxic level), Diazepam (that’s Valium), Diazepam metabolite, Ethinamate (Valmid), Ethchlorvynol (Placidyl), Amobarbital (Amytal), Pentobarabital (Nembutal), Pentobarbital (Carbrital), Meperidine (Demorol), Phenyltoloxamine (Sinutub), and last but not least, Elavil and Avaentyl, both anti-depressants. Medicines, right? Not drugs.” Harbinson nailed Elvis’ denial of prescription drug addiction perfectly.

• Elvis’ reverence for Brando not returned

Harbinson has Elvis comment on many other controversial topics, including Priscilla, Ann-Margret, spirituality, guns, and his meetings with The Beatles and President Nixon. Little is said on some other subjects of interest, such as the Memphis Mafia, but 41 pages is not enough to cover all the facets of Presley’s complex life and career. In the closing pages, Harbinson has Elvis sum up his life’s greatest triumphs and failures. There are really no surprises here, but in having Elvis testify to his regrets, Harbinson comes closest to aligning his voice with Elvis’ true “iconic” voice.

Elvis’ fascination with Marlon Brando is another thread that runs throughout this narrative, and Harbinson uses it as a bridge to the Brando essay that follows it. Elvis recalls a chance, momentary meeting with Brando in the Paramount commissary during the filming of King Creole. “Maybe that small incident,” Elvis reflects, “more than any other, more than the records and the movies and the money and the many women, the highs and the lows, the successes and the failures, reminds me of all that I won and then lost, of what I most wanted to attain, but never did. Yeah, it’s that single, still vivid, abiding memory, going round and round in my head like a ribbon of dreams. I once shook hands with Marlon Brando.”

It’s a poignant thought to end Harbinson’s Elvis narrative … but then you turn the page and immediately read about how Brando once told Playboy magazine that Elvis was a bloated, over-the-hill adolescent entertainer who had nothing to do with excellence, just myth, and that the handshake at Paramount meant nothing to him. It’s a reminder that even the most cherished dreams of our idols often don’t come true. — Alan Hanson | © November 2011

Go to Elvis Books

Go to Home Page

"Presley fans can expect to react with alternating passions when reading the treatment that Presley’s life gets in 'Iconic Vocies.'"