Elvis History Blog

New York Columnist Jack Gould

Led the Assault on Elvis in 1956

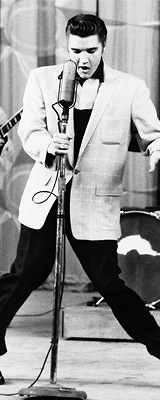

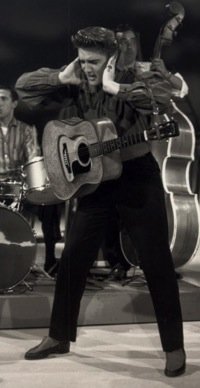

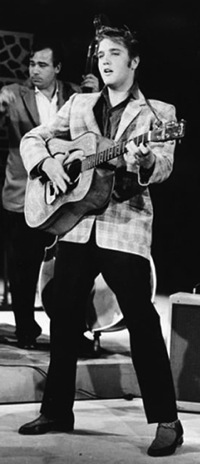

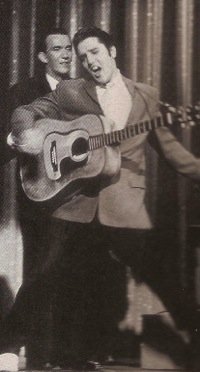

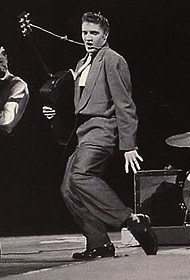

Elvis Presley’s TV appearances in the summer of 1956 brought the young rocker a torrent of criticism from newspaper editorial writers and columnists. Most were content to voice shock and indignation over Presley’s stage antics, but a handful of the nation’s most prominent journalists attempted to use their powerful pulpits in the press to marginalize Elvis and limit his growing influence over American teenagers. Among this coterie of writers determined to box in Presley were Jack O’Brien of the New York Journal-American, John Crosby of the New York Herald-Tribune, Ben Gross of the New York Daily News, and Dick Williams of the Los Angeles Mirror News.

However, the de facto leader of the press campaign to immobilize Elvis in 1956 was Jack Gould, TV reporter and critic for The New York Times. Gould’s widely read columns and reviews were influential with TV network insiders. According to Wikipedia, “Gould was heavily critical, yet optimistic, on the potential power of the television medium as a force for social good.” It was no surprise, then, that he weighed in heavily on the Elvis Presley controversy in 1956.

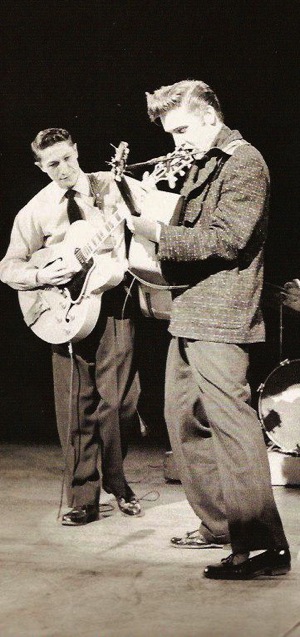

Gould wrote two principal columns on Elvis that year. The first appeared in the Times on June 6, 1956, the day after Presley’s notorious performance of “Hound Dog” on The Milton Berle Show. The second column ran in the September 16 issue, a week after Elvis’ first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show.

In both articles Gould dismissed the notion that Elvis’ popularity was based on his talent. “Mr. Presley has no discernable singing ability,” he declared in the June column. “His specialty is rhythm songs which he renders in a an undistinguished whine; his phrasing, if it can be called that, consists of the stereotyped variations that go with a beginner’s aria in a bathtub. For the ear he is an unutterable bore.” In September, Gould reported that on the Sullivan show, Elvis “injected movements of the tongue and indulged in wordless singing that were singularly distasteful.”

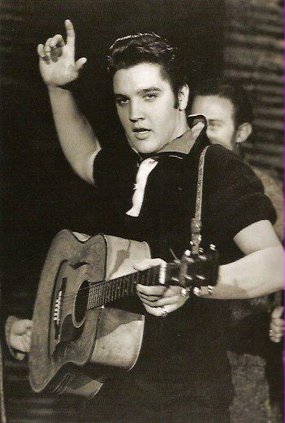

• Critics rarely analyzed Elvis’ music

This summary rejection of Presley’s singing talent by Gould and others was disputed by Karal Ann Marling in her 1996 book, As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s (Harvard University Press). “Critiques of the [Sullivan] programs assumed that the Presley appeal was strictly telegenic—not vocal,” noted Marling. “His vocal style, in fact, was every bit as mobile as his hips. Since most of the journalists on the Elvis beat denied him any artistry, his two-and-a-third-octave range was never mentioned and the music itself was rarely analyzed.”

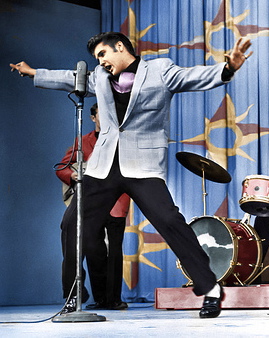

Denying Elvis even a modicum of talent allowed Gould to attribute Presley’s popularity solely on an unwholesome sex appeal. “From watching Mr. Presley,” Gould proclaimed, “it is wholly evident that his skill lies in another direction. He is a rock-and-roll variation on one of the most standard acts in show business: the virtuoso of the hootchy-kootchy. His one specialty is an accented movement of the body that heretofore has been primarily identified with the repertoire of the blonde bombshells of the burlesque runway. The gyration never had anything to do with the world of popular music and still doesn’t. Certainly, Mr. Presley cannot be blamed for accepting the adulation and economic rewards that are his. But that’s hardly any reason why he should be billed as a vocalist. The reason for his success is not that complicated.”

In his June column, Gould did not openly charge Elvis with the sexual corruption of teenagers, but in his column after the first Sullivan show, the writer do so openly. “In the long run, perhaps Presley will do everyone a favor by pointing up the need for earlier sex education so that neither his successors nor TV can capitalize on the idea that his type of routine is somehow highly tempting yet forbidden fruit.”

Gould then moved on to assigning blame for what he perceived as Elvis’ unwarranted popularity. He gave both the performer and his teenage fans a pass. “Neither criticism of Presley nor of the teen-agers who admire him is particularly to the point,” Gould explained. “Presley has fallen into a fortune with a routine that in one form or another has always existed on the fringe of show business; in his gyrating figure and suggestive gestures the teen-agers have found something that for the moment seems exciting or important.” Instead, Gould assigned some blame to parents, who had failed in his opinion to maintain firm control in an era when television content was infecting their kids with a premature desire for independence.

The main culprits, though, in the sordid Presley phenomenon, according to Gould, were the television network executives for adopting a code of “giving the public what it wants.” All well and good for adult audiences, allowed the columnist, “but when this code is applied to teen-agers just becoming conscious of life’s processes, not only is it manifestly without validity but it also is perilous.”

• TV allowed Elvis to “overstimulate” America’s youth

It was not a censorship issue to Gould, but rather just a matter of common sense. “Selfish exploitation and commercialized overstimulation of youth’s physical impulses is certainly a gross national disservice,” he declared. By allowing Presley to project his sex act directly into the American home through their medium, TV broadcasters were placing commercial profit above their responsibility to the American people. Or so Jack Gould saw it in 1956.

“Television broadcasters cannot be asked to solve life’s problems,” he asserted. “But they can be expected to display adult leadership and responsibility in areas where they do have some significant influence. This they have hardly done in the case of Elvis Presley.” The solution was obvious to Gould—the television networks should refuse to give further exposure to Presley’s “hootchy-kootchy” act, regardless of what the public wanted. He also suggested that the music-publishing industry, which had “disgraced itself with some of the ‘rock ’n’ roll’ songs it has issued,” pull such rubbish from it public offerings.

Thus Jack Gould’s plan to marginalize and immobilize Elvis Presley involved enlisting the aid of parents, TV broadcasters, and music publishers. The Times columnist, however, clearly failed to understand that by portraying Elvis’ influence as immoral, he instead was adding fuel to the Presley flame. The following two letters printed in the Times a week after Gould’s September Presley column, enlightened the writer to the obvious unintended effects of his anti-Elvis rants.

“I am 18 years old and have wide contacts in teen-age circles. My experience would seem to indicate that if it were not for the dubiously sincere moralizing of such men as Mr. Gould, the whole question of Mr. Presley’s sexuality might never have arisen and he might not be the national craze that he is today.” | Fred Barreiro Jr., New York

“The teen-age minds reacted toward Elvis Presley as they have toward other American favorites. In no way did they feel a sense of stimulation with a sex-defined attitude. It was puppy love and no more than any admiration that exists between the idol and his fan. Adults who forever misunderstand the desires of these teenagers immediately took up the cries of ‘suggestive performance,’ ‘degrading routines; and ‘sexual gyrations.’ Believe me, the teen-agers were not aware of this interpretation until it was presented to them by the unhealthy few.” | Mrs. Rhoda Frank, New York

Thus, while Elvis fans in the fifties surely resented Jack Gould’s criticism of their idol, they also owed him a debt of gratitude for his unwitting contribution to Presley’s exploding popularity in the latter half of 1956. — Alan Hanson | © June 2011

Go to Elvis 1956

Go to Home Page

"Mr. Presley has no discernable singing ability. His specialty is rhythm songs which he renders in an un-distinguished whine."