Elvis History Blog

Chatelaine Magazine—June 1957:

Why Do Canadian Youngsters Worship Elvis Presley?

by June Callwood

A current phenomenon, a twenty-two-year-old, soft-bodied singer named Elvis Presley, came to Canada for two nights early in April this year. In a gaudy gold suit, he performed before twenty-three thousand in Toronto and eight thousand in Ottawa, most of them girls in their early teens who risked anything from parental scorn to expulsion from school to watch him. Among the screaming, swaying mass that packed Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens was an Elvis Presley super-fan, Carol Vanderleck, fourteen, and intelligent, even demure, high-school student who collected three thousand names on a petition begging Presley to visit Toronto.

In the press-lashed furor that preceded his coming, many adults would have picked Carol Vanderleck as an outstanding and misguided victim of a craze that has been labelled disgusting, immoral and stimulating to delinquency. But in the wake of the Presley performance, a few people, like myself, who were close to him during his visit firmly believe the most unfortunate young person in the Gardens that night was Elvis Presley himself.

As child psychologists and psychiatrists were steadily pointing out throughout the hubbub of derision and disapproval, Carol Vanderleck and her associates were exhibiting normal symptoms of adolescent growth. They were banded together within their own cult to give themselves a feeling of solidarity. This is a natural stage of development in the early teens, where the sense of strangeness and apprehension is acute. They had selected a symbol to admire, one who combines everything prohibited them—untidiness, garish dress, exhibitionism, defiance of rules, wealth, and freedom enough to buy purple Cadillacs at whim.

Best of all, the Presley-symbol sings with a strong, primitive beat that matches the throbbing pulse of a teen-ager who has just discovered her body is no longer childish in outline and longing. As entertainment history proves relentlessly, most teen-agers mature and discard their former heroes with thoughtless ease. Rudy Vallee’s most ardent fans of the past are now grandmothers. The set that swooned at Frank Sinatra is approaching middle age. Johnnie Ray’s weeping bobby-soxers are young mothers. In a year or two the present Presley fans will have outgrown him, without noticing the transition. The only unique aspect of Presley’s appeal to young adolescents is its penetration.

Because of television, improved record distribution and promotion, and the alacrity of Hollywood in hustling his face on the screen while the comet was at its zenith, Elvis Presley has become the best known idol of them all. Presley earns a reported two to three million dollars a year, has sold sixteen million single records, heads a corporation that sells sixty different Elvis Presley-brand items, from lipstick to shoes, and charges a quarter of a million dollars’ fee for a movie.

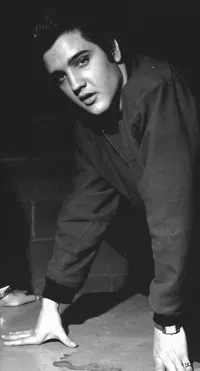

In Toronto his two performances brought in fifty-four thousand dollars, according to Variety; his Ottawa gross was thirty-two thousand. His overhead, according to his manager, is fifteen thousand dollars a day. Three years ago Presley was driving a truck for thirty-five dollars a week. He is now what he was then, a semi-literate Tennessee youngster with a man’s body and lusts, and the simplicity of a guileless ten-year-old. His God-fearing parents, faithful members of a congregation known as the Assembly of God, raised their only child, Elvis Aron Presley, to tell the truth, to be respectful to his elders, to refrain from drinking, smoking and stealing He obeys all these injunctions firmly and with obvious pride in the tenacity of his character. A part of himself that he apparently considers beyond the rigid rules of Southern decorum is his excessive sexuality. He makes no effort to conceal that his enthusiasm and appetite for women is hearty. Asked in Toronto if he is thinking of marrying, Presley replied with a half smile—and lively flicker in his eyes, “I’ve thought about it, but when I think about being married to just one woman—uh huh.”

When he poses with teen-age girls—a procession of whom turn up after every press conference for various publicity reasons—he always manages to squeeze the prettier ones, sniff their hair, check their configuration minutely and kiss a few on the cheek. In Toronto, he selected a stunning blonde for special attention, coated her from head to foot with a warm look—and suggested she drop back after the show. The invitation was ill-advised though, since Presley’s show ran late in Toronto and he was hurried straight from the stage to the train for Ottawa. In all matters, Presley is as uncomplicated and direct as he is in his dealing with women.

He always is received with sincere admiration by newspaper reporters and photographers because of his unfailing candor. He looks unabashedly at his questioner and answers with unvarnished truth. When the question contains a word he doesn’t understand—a rather frequent occurrence—he never bluffs. “I don’t know that word,” he confesses, without embarrassment.

Among the words new to his vocabulary in Toronto were “annuities” (he was asked if he was providing for his parents by means of annuities), “sinister” and astonishingly, “range”—meaning his voice. “What is your range?” a reporter asked him. Presley looked stunned. “Your voice,” someone contributed. He looked relieved, and amid laughter which he shared, answered. “I don’t know. I don’t read music at all. In my line of music, you don’t have to.” “Do you like classical music?” someone maliciously asked. “I don’t understand it. I just don’t understand it,” he answered. “I’ve got some of it at home.” “Do you ever play it?” “No, sir, I don’t.”

The bitterness many parents feel toward Presley bypasses the rather disarming openness of his nature and concentrates on the lewdness of his performance. This is the aspect of the Presley mania that most parents find unacceptable: the fact that it is so flagrantly rooted in eroticism. Through the grace of television, there is little doubt in most adult minds that Presley’s stage movements are as highly charged with sexual suggestion as a burlesque queen’s. He bumps and grinds his hips in a style that has had but one meaning throughout the centuries since Salome danced. Middle-aged men of small maturity ogle strippers with approximately the same glazed and inward-turned expression that teen-agers, also of small maturity, watch Elvis. But some observers detect an enormous basic difference.

“What about Carol”

There is no question, of course, that Presley doesn’t know the meaning of his gestures. He is a worldly youngster. There is real reason to suspect, however, that he sincerely believes his behavior is well within the bounds of good taste. He is aggrieved and hurt as a child when witty reviewers, using words he can’t comprehend, ridicule him in a tone he can divine behind the words. Encased, as he has been since his success began, in bodyguards and sharp-thinking managers, he is apparently unaware that many people consider him obscene.

On the other side of the footlights at the Presley performance, the young teen-agers who enjoy a mass orgiastic reaction have little inkling of the implication of the movements that make them scream. They are at an age when their developing bodies have passed their own understanding, according to experts who have made a thorough study of adolescents. They must dance vigorously, take part in sports with shrill enthusiasm and scream whenever possible to work off superfluous excitement. Presley, with ungainly competence, fills their need.

When the news that Presley was coming to Canada spread through Toronto and Ottawa, many parents made the decision to refuse their children permission to attend. They were concerned at the real danger of a riot developing, as well as the emotional lacerations of the Presley singing technique. Mr. and Mrs. James Vanderleck were among the thousands of parents who, with varying degrees of reluctance, agreed to let their offspring see Elvis. Carol Vanderleck regarded as something of a celebrity herself around her high school because Presley’s manager personally had telephoned to thank her for the three-thousand signature petition, considers herself an average Presley fan.

If she is, the average Presley fan is good citizen material. Carol lives in a well-tended but not pretentious neighbourhood. Her father is a professional engineer and the family is church-going. She was a member of the Brownies when she was small, and then the Girl Guides. She sang in the church choir and is a better-than-average student. She was in high school when she was twelve and is still near the head of her class. Considering solemnly the virtues of her hero, Carol recently observed, “We teen-agers like Elvis because he’s … well, different. His sideburns, everything about him is different from anyone else. It’s funny but the things parents don’t like about Elvis are exactly what we like most about him.”

This remark amused one of Canada’s leading psychiatrists, Dr. J.D.M. Griffin of the Canadian Mental Health Association. “That’s the whole point,” he said. “Children of this age are certain to disagree from time to time with their parents. It’s a healthy way of experimenting with independence. It’s a perfectly natural symptom of personality development.” Carol Vanderleck had been collecting pictures of movie stars for about a year when she first became a Presley fan. She saw him in his first movie, Love Me Tender, and screamed exuberantly all though it. Afterwards, she diverted all her allowance money (seven-fifty a month) and everything she could earn from baby-sitting to the purchase of Elvis Presley gimmicks, such as a plastic wallet stamped with his picture.

One day, early in January, Carol’s mother overheard her talking with some friends. “Elvis visits hospitals,” one of them was saying dreamily. “If he comes here,” commented another, “let’s break our legs and then he’ll come and visit us.” “But how are we going to get him to come here?” protested the first. “I’ll figure something out,” promised Carol. “If I had known what she planned to do,” grinned Mrs. Vanderlack later, “I’d have broken all her fingers.”

Carole wrote to disk jockeys in Toronto, Buffalo and Hamilton, asking them to announce that she needed signatures on petition to request a visit from Elvis. She figured she’d wait until about three hundred had been mailed to her and then she would forward them to the Presley headquarters. The response was so gratifying—to her that is—that she stayed with the project until more than three-thousand names had arrived. She sent them to Presley and was ecstatic when Colonel Tom Parker, Presley’s manager, telephoned to thank her.

Shortly afterward Presley announced that Toronto would be included in the tour of one-night stands he was planning between the making of his second and third motion pictures. Normally inclined to be intense anyway, Carol’s excitement flared so high that the family doctor ordered sedatives.

As the day of Presley’s arrival neared, Mrs. Vanderleck remarked dolefully, “I am eying that bottle of sedatives and wondering if there is enough for both of us.” The situation in the Vanderleck house, already highly volatile because of newspaper and radio interviews, became a notch more explosive with the arrival of a Galt shoe manufacturer, Robert Woolley, who had purchased the Canadian franchise to produce Elvis Presley ballerina shoes. He wanted to arrange for Presley to present a pair of them to Carol and use the resultant photograph in his advertisements. Carol’s reaction was delirious. Her father said sternly, “I’m coming along.” Carol met Presley just after his press conference in a square concrete room in Maple Leaf Gardens. The conference was attended by the oddest assortment of reporters, columnists and disk jockeys that has ever graced a mass interview A famous woman fashion commentator, swathed in pale mink, sat beside a man who announced he was the dean of country music in Canada and wore a white Stetson, pancake make-up and a red string tie to prove it The room was furnished with a plywood folding table near the door and rows of benches arranged in front of the table. Presley’s appearance was heralded by the arrival of one of his two bodyguards, a heavy man with a mean dull face, then his manager Colonel Tom Parker, a former carnival promoter with the shrewdness of his kind, and two small, slight and sleepy men who slouched against the wall. There were Presley’s cousin and a Tennessee disk jockey, respectively, who accompany Presley on road trips to stave off the loneliness that sometimes grips him.

“Wear these for me”

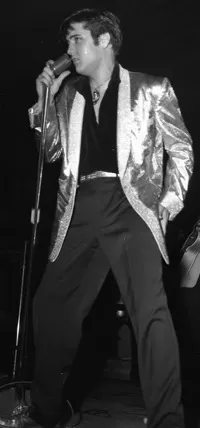

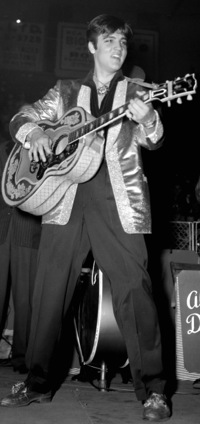

Elvis arrived a moment later and made even the dean of country music appear staid. He wore a silver lamé shirt, ruffled down the front and studded with rhinestones, a black belt studded with rhinestones set in gold, black trousers, gold shoes with tassels speckled with sequins, and a red windbreaker. He sat on the table, linked his hands around his knees and, completely relaxed, waited for questions. When did the kids first start screaming? “The first time I sang in public. I didn’t know what I was doing; everyone was yelling and I didn’t t know what they were yelling at. When I came off the stage my manager said, “You keep that up.’ I didn’t know what he was talking about.” What is your advice to teen-agers? “My main advice is to say in school. I used to think school was for the birds, but now that I’m out meeting people I realize how important it is.” Did you use to dream about success? “When I was a kid I used to lie under the tree with my cousin here and we’d talk about how good it would be to have money and travel and good-looking women and cars. Now we have it and it doesn’t seem real.” Carol was ushered into the conference room shortly after this. Her face was white and she was wearing her best tartan suit. Mr. Woolley, the shoe man, looked agitated and breathless. He pressed a pair of black patent shoes into Presley’s hands. Presley was startled and sent an enquiring look at his manager, who nodded.

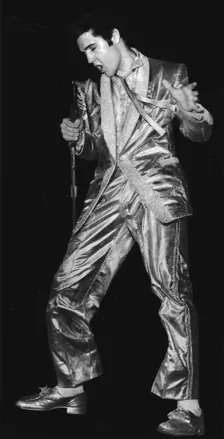

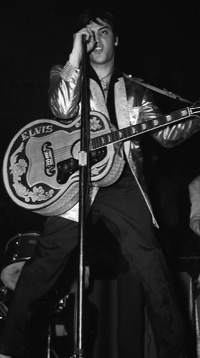

As a photographer prepared to take the picture, Woolley hurriedly instructed Presley. “Say, ‘Here you are, honey. Wear these for me,’” he said. Presley put an arm around Carol, who flushed pink, and obediently repeated the sentence. A moment later Carol was outside the room where her father waited. She seemed stunned. “He talks with an accent,” she gasped when she was pressed for a reaction. Her father gently led her away. Now that the stupefying effect of Presley’s haberdashery had faded with familiarity, the press noticed that Col. Parker was wearing a mauve tie bearing the noble inscription, “Elvis is the Most.” The Colonel and Presley’s publicity man, Tom Diskin, efficiently cleared the conference room. “Elvis has to get changed for his performance,” Diskin announced. “You’re welcome to leave now, if you like.” Presley wore, for his Canadian appearance, a suit woven of gold thread with jeweled lapels.

In Chicago, where the suit was unveiled for the first time, it was reported to be worth twenty-five hundred dollars, but by the time Elvis reached Toronto three days later, its reported value had increased to four thousand dollars. He sang in Toronto from a stage at one end of the Gardens, while more than eighty policemen prowled the aisles and stairs to watch for the spark of hysteria that can set off a panic. Gardens’ ushers assisted, firmly pushing into their seats all youngsters who leaped up. Because of the constant screaming, it was impossible to hear Presley sing at all. Sometimes, he admits, he can’t even hear himself. Throughout most of the pandemonium, Carol Vanderleck sat rigid with her fists clenched against her throat. While some wept (most shrieked and a few booed), she watched Presley with silent intensity. Her father sat nearby, not too absorbed in guarding his daughter to be unamused at Presley. After the first of the two shows that Elvis did in Toronto, another hasty and brief press conference was called At this one I was able to approach Presley separately and question him. “Elvis, people who study teen-agers a good deal believe that you represent a way of growing up. Through admiring you, the kids can demonstrate to their parents that they are becoming adults and are ready to have opinions of their own. What do you think of this?” Presley looked confused. “Honey, I don’t understand that at all.”

He was interrupted by a request for autographs. “Don’t go away,” he begged. “I’d like you to explain that.” Col. Parker rushed up. “What did you ask him?” he demanded harshly. The question was repeated and the manager’s expression grew more anxious. “Don’t tell him that again,” he said earnestly. “If he starts to try and figure the thing out, he may lose what he’s got. He’s better off not knowing what it’s about, don’t you agree?” It was impossible not to agree.

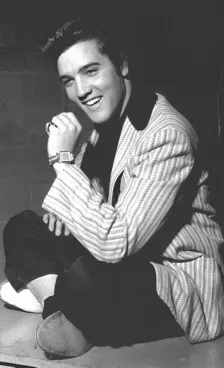

When Presley turned back for an explanation, Col. Parker told him genially. “Never mind. We’ve got it all straightened out.” Presley looked baffled, then shrugged. He moved away, signed a few more autographs and scowled into the flash bulb of another camera. He has been advised that his teen-age fans adore his scowl so he tries to remember to look brooding in his photographs. While he is prone to childish pique and occasional high-flaring temper, Presley normally has the bouncy cheerfulness of a small boy at a perpetual party. He stood loosely, waiting for the room to clear, a big youngster with a long, soft face pale from night-living and day-sleeping and his body thickened by a haphazard diet that includes a lot of starches and soft drinks. He wiped his hands on the plump seat of his golden pants. His expression was polite and patient as the last of the reporters filed past the bodyguard and the door was closed. Later he stood on the stage in his gold suit, drenched in spotlights and screams, weaving his heavy body in the manner that feels good to him and seems to get results.

His manager watched him with satisfaction. “He minds good,” he commented. Carol Vanderleck went home with her father that night, exhausted and close to stupor. Her parents nevertheless were unconcerned for her future. In two days she was back to normal and swept up in school activities. “I’m glad she had the experience,” observed her mother. “It was very trying for us but it’s something she’ll remember all her life.” Mrs. Vanderleck’s attitude is a contentious one. A convent in Ottawa temporarily expelled eight girls for attending the Presley performance and households all over Toronto and Ottawa were rocked by the conflict between parents and teen-agers that Presley’s arrival brought to a head. But many experts on adolescent growth agree with Mrs.Vanderleck that Carol will outgrow Presley long before she outgrows her new tartan suit. The question that occupies far less attention seems to some observers the greater one: How can Elvis Presley mature without destroying himself? His prospects look heavily seeded with tragedy.