Elvis History Blog

CD Set Released in 2016 Recalled

Elvis Presley's Jungle Room Sessions

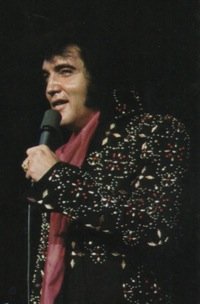

Nearly four decades after his death, RCA Records continues to periodically repackage and reissue Elvis Presley’s music. In summer 2016, the company put the two-CD compendium “Way Down In the Jungle Room” on the market. It focused on Presley’s final recording sessions in 1976. In February and October of that year, RCA brought its mobile recording truck down from New York and parked it behind Graceland. Cables were run into the den at the rear of the mansion, and a RCA engineer transformed the chamber, since known as the “Jungle Room,” into a recording studio. Accompanied by many of his regular musicians and background singers, Elvis there laid down the last studio tracks of his career.

CD #1 in the “Way Down” set contains the 16 original masters recorded during the two Jungle Room sessions. The second CD offers what the RCA packaging labels “newly mixed alternate takes.” Most had been previously released, but many were stripped of the excessive overdubbing originally applied to the master takes, bringing Elvis’ voice more to the forefront. Additionally, some listeners may find of interest the added studio banter between Elvis and the musicians.

The CD set came with a 22-page booklet of photos and an interesting short essay by John Jackson. I’m not familiar with any previous Presley writings by Jackson, but the following bio information about him in the booklet certainly gives him some credibility on the subject:

“John Jackson graduated from Indiana University in 1997 with the world’s first Bachelor of Arts degree in Rock and Roll History, delivering a thesis project on the life and cultural impact of Elvis Presley.”

• Jungle Room recordings have emotional impact

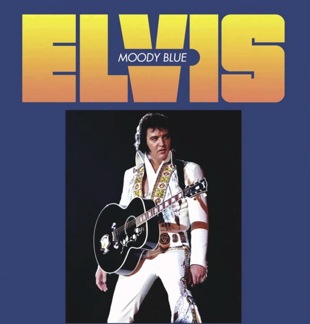

For those of us who were Elvis fans leading up to the last 18 months of his life, the Jungle Room recordings can evoke a strong emotional reaction. After all, the final two LPs and the final three singles of his life came from those 1976 sessions. Presley followers who had for years waited patiently to purchase his latest records saw that joy come to an end with the “Moody Blue” album and the “Way Down” single.

Looking back dispassionately, though, the 1976 sessions pose three historical questions … (1) Why did they take place at Graceland? (2) How did Elvis’ state of mind affect the music? (3) What was the quality of the recordings produced in the Jungle Room?

As on many issues throughout his life, Presley experts offer various, often conflicting, answers to those questions. Jackson gives a positive, Presley-centric spin on the topics, while biographer Peter Guralnick and Presley sessions expert Ernst Jorgensen take a more candid approach.

For instance, on why Elvis recorded at Graceland in 1976 and not at a standard recording studio as he always had before, Jackson contends it was simply an artistic decision that Elvis made. With his hectic touring schedule, he wanted to spend as much time as possible at home in Memphis, Jackson notes. With the closure of American Sound Studios and Stax studio, where he had previously recorded in Memphis, Elvis made the decision to do what many other cutting-edge musical groups were doing then—record in an informal setting.

Both Guralnick and Jorgensen, though, say Elvis was virtually forced into recording at Graceland. “It was becoming impossible to get Elvis even to consider going back into the studio, despite the obligation of his RCA contract,” Jorgensen maintained in his complete Elvis recording sessions book in 1998. Elvis’ contract called for RCA to release two albums per year, which would require a minimum of 20 new tracks from Elvis.

In his 1999 Presley biography, Guralnick asserted that the decision to record at Graceland was not the singer’s. “Both Colonel and RCA were in full agreement: they needed to obtain product from an artist who appeared to have developed an almost pathological aversion to the recording studio,” Guralnick noted. “They now proposed simply to install temporary equipment in the den behind the kitchen, run lines out to the RCA mobile recording truck that would be parked behind the house, and make the best of whatever sound deficiencies arose.”

• The Jungle Room sessions failed to meet goal

Presley’s producer, Felton Jarvis, set a goal of 20 new masters, enough for the two contracted albums, over six days of recording at Graceland in early February 1976. Over seven days, though, from February 2-8 only a dozen cuts were completed. For the record, they were “Bitter They Are, Harder They Are,” “She Thinks I Still Care,” “The Last Farewell,” “Solitaire,” “Moody Blue,” “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” “For the Heart,” “Hurt,” “Danny Boy,” “Never Again,” “Love Coming Down,” and “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.”

Despite the failure to meet the quota, John Jackson credited Elvis with creating a fertile and enjoyable work atmosphere:

“After settling in to the new set up, the sessions became relaxed, productive and most of all fun … In the outtakes and studio chatter you can hear the inside jokes, the gentle ribbing and the music discussion that any band have. Improving the feel of the plan of attack was paramount and everyone was on board to allow Elvis the musical foundation he was looking for.”

According to Jorgensen, though, Elvis was not taking his obligation seriously: “Nothing Felton could do would stop Elvis from wasting hours on Morris Albert’s ‘Feelings,’ or singing every Platters song he knew.” Guralnick expounded on Elvis’ tendency to waste significant amounts of time during the first Jungle Room session:

“[The first night] everyone was waiting patiently for him to emerge from his bedroom, trying not to wonder if he was going to show up at all … On the second night, Elvis succeeded in recording just one song, while spending most of the time trying to avoid accomplishing even that. He returned to his bedroom periodically throughout the evening, took one member of the band or another upstairs to listen to gospel music, expounded upon numerology, and gave them all a viewing of his collection of police badges. The third night was no better; most of the time Elvis appeared to be struggling just to wake up.”

Not until the fourth night did Elvis and the band seem to “kick in,” according to Gualnick. Elvis got into the uptempo “For the Heart” and his enthusiasm continued with an emotional interpretation of “Hurt,” which included a “highly charged recitation of the most melodramatic sort.” Then came “Danny Boy,” one of Elvis’ old favorites. “He was fully engaged now,” noted Guralnick, “and while he was not able to sing the song in the key that he originally selected, he hung in through ten takes until he got a version even more heart-rending.”

Unfortunately, Elvis couldn’t carry the enthusiasm over to the next three nights. Only two cuts were completed on the fifth night and only one on the sixth night. Felton Jarvis extended the session for another night, but Elvis was a no-show altogether. With barely over half the masters he needed, Felton had to schedule another Graceland session. Due to Presley’s extensive tour schedule, though, he had to wait eight months to get Elvis back into the Jungle Room.

• Elvis … “He just wasn’t interested”

The October 29-30 sessions were even less productive, resulting in only four masters: “It’s Easy for You,” “Way Down,” “Pledging My Love,” and “He’ll Have to Go.” Jackson described the fall sessions as being “a little more loose, with Elvis spending more time goofing around or preoccupied with guests to the house. This is the downside of the home studio—a little TOO much freedom.”

Pianist Tony Brown described Elvis’ apathy toward these sessions. “He just wasn’t interested. He couldn’t seem to keep rhythm, he couldn’t maintain any attention span; it was like we’d get one song, and he’d go upstairs for a couple of hours, and we’d just wait around.”

Jorgensen gives one example of Elvis' wavering interest on the second night of the sessions. “It was the night before Halloween, and when Elvis and some of his friends returned late they were dressed in gangster outfits and guns that must have alarmed the newer band members. The costume party effectively put an end to the evening’s work.”

Guralnick explained how Elvis finally concluded the ill-fated session:

“Any pretense that the session might continue was abandoned when Elvis once again retreated to his room … Elvis put an end to any such speculation by apologizing and declaring that he was simply too distracted to continue. He was upset about Red and Sonny’s book, he said, and he couldn’t get in the right frame of mind for recording.”

• The Jungle Room Recordings were a mixed bag

Other events conspired to keep Elvis from getting into the right frame of mind to record in 1976. Fallout still lingered from his divorce from Priscilla, and now his girlfriend Linda Thompson was about to leave him. The failed racquetball business deal still haunted him. “I’m so bored,” he told background singer Sherrill Nielsen. “I’m so tired of being Elvis Presley.”

Despite the emotional malaise sapping Elvis’ enthusiasm in 1976, some quality cuts emerged from the Jungle Room sessions that year. Jorgensen noted that Elvis’ choice of material then weighed heavily toward “regret-filled, almost maudlin numbers that continued to speak to Elvis and his abiding despair during these years.” Over half of the 16 Jungle Room masters were wrenching ballads, including “Solitaire,” “Never Again,” “Love Coming Down,” and “It’s Easy for You.” None of these tracks are out of the ordinary, and so are left to the personal judgment of listeners.

“Hurt” was one exceptional ballad recorded in the Jungle Room. Jorgensen heaped praise on Elvis’ interpretation of the Roy Hamilton’s 1955 r&b hit:

“Draping its lyric of abandonment over a hugely demanding melody, it evoked in this troubled, exhausted singer a performance of spellbinding ambition and sincerity. ‘Hurt’ was probably the most convincing recording of Elvis’ twilight career.”

Guralnick offered this comment on Elvis’ recording of “Hurt”:

“There is a note of triumph on Elvis’ part, a pride in simply being able to get out what he is trying to say. This, he declares with as much bravado as he can muster, is who I am—despite all the pain, despite all the suffering, despite all the hurt, you can see: I’m still here.”

Also of note are Elvis’ renditions of three rhythm numbers. In “For the Heart,” Jorgensen observed, “For the moment Elvis seemed to relax and enjoy the easy rocker, and the musicians were certainly fired up by the sly, swinging tune.” Guralnick agreed. “Elvis seemed to respond to it, gaining confidence through numerous rehearsals and multiple takes until the song became the kind of seductively driving rock ’n’ roll that had once been a staple of Elvis Presley music.”

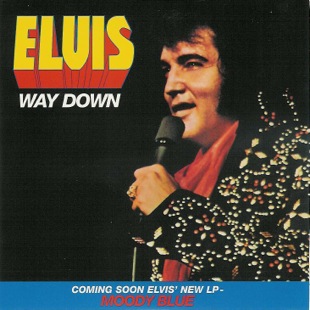

Elvis also mustered the energy to make strong recordings of uptempo numbers “Moody Blue” and “Way Down.” RCA chose both, along with “Hurt,” as the “A” sides of the three singles from the Jungle Room material.

Jorgensen also had special praise for Elvis’ treatment of “Pledging My Love,” a 1954 Johnny Ace number.

“Elvis sank his teeth into his own version, drawing on his knowledge of the original recording and the musical moment it came from—that moment in the mid-‘50s when blues, country, and gospel were coming together for the first time. Completely caught up, he wrenched every emotion out of the simple lyric.”

Ultimately, each Elvis fan retains the option of choosing which of the Jungle Room recordings to cherish and which ones can be put aside. Personally, I consider “Solitaire,” “Moody Blue,” “For the Heart,” and “Pledging My Love” on par with anything Elvis recorded in the ’70s. His rendition of “Danny Boy” is my favorite among all the recordings I’ve heard of that classic song. Finally, I especially enjoy the alternate take of “The Last Farewell” on the 2016 Jungle Room CD package. Removal of the overdubbed strings and horns allows Elvis’s clear voice to come forward on the charming historical love song.

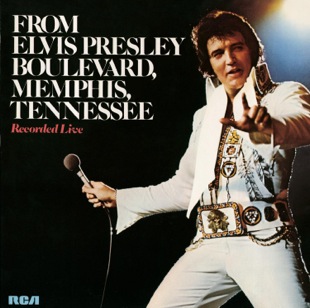

• Jungle Room releases were on the charts when Elvis died

For the record, “From Elvis Presley Boulevard Memphis, Tennessee,” an album with 10 cuts from the February Jungle Room sessions, did poorly on the Billboard LP pop chart. Released in March 1976, Elvis’ 69th record album reached only #41 on the chart. The two singles issued from those sessions achieved average chart success, by Presley standards, in the mid-‘70s. The “Hurt”/“For the Heart” pairing spent 11 weeks on the Hot 100 in the spring of 1976, peaking at #30. “Moody Blue”/“She Thinks I Still Care” fared about the same, staying on the chart for a dozen weeks in early 1977, topping out at #31.

The chart performances of Elvis’ last album, “Moody Blue,” and his single, “Way Down,” were quite unusual, due to the fact that both were currently on Billboard’s respective charts when Elvis died. The demand for Presley records after August 16, 1977, resulted in “Moody Blue” rising quickly to #3 on the LP chart. The “Way Down” single had spent 10 weeks on the Hot 100 and was about to fall off the chart, but when Elvis died the single shot back up the list, reaching as high as #18 in late September. By the time “Way Down” dropped off the chart for good in November, it had spent 21 weeks on the Hot 100, a total comparable to many of Elvis’ biggest hits.

When they ended in October 1976, no one knew, of course, that Elvis Presley’s Jungle Room sessions at Graceland would be his last. Another session was quickly planned for January 1977 in Nashville. Songs were chosen and all the musicians were on site, but Elvis was a no-show. He made it to Nashville, but stayed holed up in his hotel room for several days before returning home to Memphis.

Next time you hear Elvis’ recording of “He’ll Have to Go,” consider this. Of the hundreds of songs Elvis recorded in studios from Memphis to New York to Nashville to Hollywood during his career, this song was the very last one. He recorded his final vocal of “He’ll Have to Go” in the Jungle Room at Graceland on Halloween night in 1976. — Alan Hanson | © September 2016

Reader Comment: You really nailed it on the jungle room release. Still one of the saddest collection of songs ever, though probably more listenable now [on disc 2 of the new release]. — Al (September 2016)

“[Elvis] just wasn’t interested. He couldn’t seem to keep rhythm, he couldn’t maintain any attention span; it was like we’d get one song, and he’d go upstairs for a couple of hours, and we’d just wait around.”

—Pianist Tony Brown